Body Vessel Clay @ York Art Gallery

ZM

Emoji summary: 🏺 🕳️ ☁️

This week’s review is best experienced as audio - so if you’re able to, please go to the White Pube podcast on whatever platform you use to listen to podcasts. As far as I know, we’re on Spotify, Apple, Google, and of course Anchor.

I don’t know where you are right now. Maybe you’re at home in bed or on the bus. Maybe you’re in the gallery, waiting for this to start. Either way, hello, thank you for listening. I’m Zarina Muhammad, I am an art critic and I am one half of the White Pube. We’re a website, you can find us on the internet: thewhitepube.co.uk or .com. We write about art and video games and we publish a text every Sunday. We also put our texts here on this podcast, along with a couple other bonus episodes. We like to think of it as a kind of audio magazine, you never quite know what’s on the next page, but it’ll hopefully be good. Today’s review is best experienced as audio, but maybe you’re reading it as a text on the website. In which case, hey - that’s fine too. I’m going to be chatting you through an exhibition. It’s called Body Vessel Clay: Black Women, Ceramics and Contemporary Art, and it’s on at York Art Gallery until 18th September. If you are physically there at York Art Gallery, then maybe you’d like to treat this audio as a guide; have me in your ears like I’m there next to you, taking you on a sweet little tour. If you’re just at home in bed, or on the bus, or listening in at a later date once the show has closed, then you can close your eyes and treat this like a bizarre guided meditation session. I’ll try my best to help your imagination along and describe what we’re looking at. But most of all, I hope this is fundamentally just a Very Good Story.

So you’re walking into a low lit gallery room, warm spotlights glowing from overhead, shining down on a series of low white plinths. On these plinths, there are some pots. They’re spaced out, sparse. I think we’re meant to really really look at them, like really spend the time noticing the details. You can crouch down or tilt your head, get down to eye level with them if you can. I like to look first and read later, something about getting an uninterrupted first impression before you hear the spoilers.

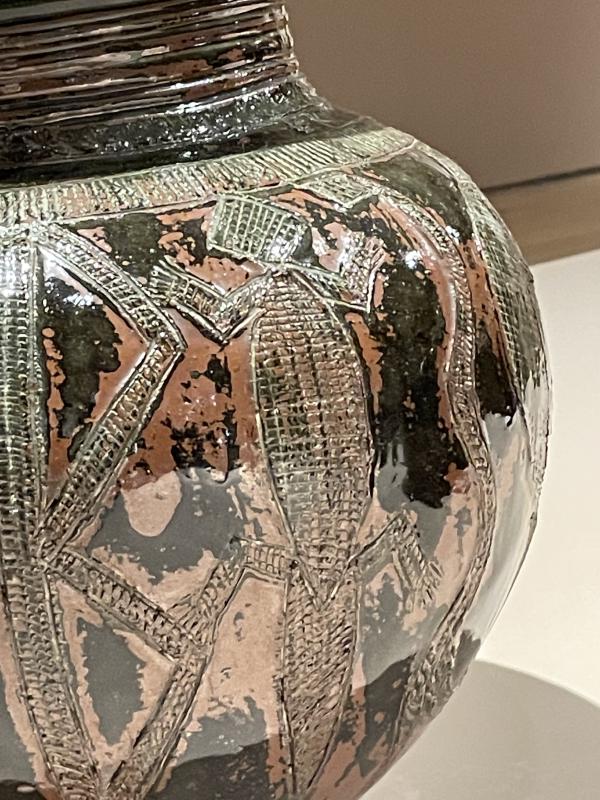

But while we look, I’ll tell you about them. Here on the first plinth, there are four pots of about the same size and shape. They all have round bodies that swell out, they dip in at the neck only to flop out at the lip. They’re a little bit wide, not very tall. They all have a similar dark green, or maybe blue, earthy tone. It’s the kind of colour that shifts depending on the light and the angle, sometimes black where the shadow sits. There are different patterns scratched into the surface of each pot, like they’ve been carefully etched out. Two are covered by detailed geometric patterns: little diamonds and lines running round in bordering strips, checkerboard panels interrupted by drawings of birds and crocodiles. The animals are geometric too, with sharp angular bodies, flattened into the essence of their own shape: triangular tails, tilted wings jutting out, heads that are perfect squares. The third is simpler: just strips of differently weighted lines and dots, texture and pattern rippling up across the surface in agonising detail. The marks are scratched in so finely, it almost hurts me to look. The last pot is slightly different. The colour on its surface peels away, exposing little bronzey orange patches. When you get close, it looks all dappled and glossy. There are those geometric style animals going round in long vertical stripes. I can’t tell what all of them are, but I can make out a crocodile again (with its round flat body, wide ribs and little arms) and an enormous fish.

These four pots were made by Ladi Kwali. I didn’t know who she was before I came to see this exhibition, so I’m going to assume you don’t either. Ladi Kwali was a potter, born in 1925 in the village of Kwali, in the Gwari region of Northern Nigeria. Back in 1925, Nigeria was colonial Nigeria, a territory ruled over by the British Empire. First, by the Royal Niger Company - you know that weird crossover between state and corporation that the British Empire kind of specialised in? Well, they were that. They were instrumental in establishing British control over the region, and they did that through ~trade~. You can’t see me, but I’m rolling my eyes because the word trade is a loaded one there. Colonialism was an exercise in capitalist expansion and trade was a violent thing. Colonial powers like Britain would establish commercial control over an area using brute force. It wasn’t professionalised or genteel free trade in the open marketplace of equal opportunity, it was more or less racketeering. But it was the Royal Niger Company first, and then they handed the territory over to the Crown and Nigeria became a formal colony. That point about colonialism being tied to capitalist expansion and trade being loaded - we’ll come back to that.

That’s the historical context, but the region Ladi Kwali was born in has an interesting history that I want to mention too. Gwari was famous for its pottery and it was work that was done traditionally and primarily by women. You know how it is, craft is historically gendered - women’s work for the home, domestic sensibilities etc etc. But maybe that’s a very Western and 21st Century thing for me to say? By all means, it seems like this was well respected work and Ladi Kwali was good at it. She learned how to make pots, jars and bowls as a child, using a method called coiling. That’s where you roll clay into a long rope, then coil it round, forming it into a solid shape, smoothing out the edges. I don’t know if you’ve ever tried it, but I found it quite painstaking. The clay takes on the shape of every touch. You have to be meticulous and careful. The mental image I have of a potter is one of a person at a wheel. The clay is in a lump, whizzing round as the potter shapes it with firm strong hands. It’s wet and earthy, but also like magic. The shape of a pot just appears out of nowhere and all of a sudden. Coiling is so much slower, it is less about magic and more about the slow build. The pot appears because you have built it. Apparently, these four pots in front of you are traditional Gwari water pots - so they were made in that painstaking hand-made coiling process. I don’t know if that changes how you feel about them, but it definitely made me feel like they were special or rare.

Now we can move over into the middle of the room, there’s a collection of smaller items in glass cases. Little pots with handles and stoppers, lots of plates and bowls, some cups. While we look at those I’m going to tell you about Michael Cardew. So around the same time tiny baby Ladi Kwali was learning how to make pots and bits, Michael Cardew was a potter who was making a name for himself in Britain. He did some experimenting, some revivalism, making pots with local clay and restoring and rebuilding derelict potteries. But there wasn’t really much money in it. So he took up a teaching post with the Colonial Service in Ghana. He read some Marx and had some interesting thoughts about how there should be a closer relationship between studio pottery and industry. For context: studio pottery has a bit more of a highbrow artisanal vibe. It’s all very handmade, unique, with artists or ceramicists making one item from start to finish (none of those production lines). I guess after the Industrial Revolution, skilled craft and the handmade became a marker of something rarified (compared to the machine-made). I’m not really sure how he got from Marx to an idea about making skilled craft-work more commercially viable through industrial methods, but the past is a different country and I’m baffled by this guy’s life story in general.

Anyway, Michael Cardew was in the right place at the right time - the Colonial Office were looking to adopt policies that would ‘develop indigenous industries’. Again, you can’t see me, but I’m rolling my eyes because I hate that phrasing. They put Michael in charge of a pottery in Alajo, a suburb of Ghana’s capital city, Accra. The idea was to train up local potters to make traditional pottery on an industrial scale. Commercially speaking, it failed. But the British Colonial Government were kind of committed to this policy. It made sense; there was a war on and they couldn’t really maintain commodity exports with that kind of threat; this was a policy of investment in art and culture as a secondary revenue stream for a colonial government that were looking to make money money money. So a couple of years later, in 1950, the British Colonial Government appointed Michael Cardew as their Senior Pottery Officer. They sent him over to Abuja, a city in Northern Nigeria, to set up the Pottery Training Centre. It was a similar venture to the pottery in Alajo; training up local men in an attempt to develop a new hybrid form. Industrial methods and techniques being applied to make ceramics that had traditional ‘indigenous’ (QUOTE MARKS, I AM USING QUOTE MARKS) sensibilities.

At first, Cardew’s trainees were all men. But then our two main characters meet - Michael Cardew stumbles across one of Ladi Kwali’s Gwari pots and he thinks they’re great. He invited her to join the Training Centre as the first female potter and she becomes a star pupil, hybrid ceramic form emerges and the rest is history - on display in this gallery in front of you, pottery as a field was changed forever. Great - that could be the end, couldn’t it? That’s the history, that’s what happened, we can see the pots and we know their backstory. But I have some questions and I want to think about them with you. I don’t know if it’s the same for you, but there are so many parts of this neat cultural backstory that make me feel deeply uncomfortable. For one, there’s a colonial discomfort; the pots have an entire backstory where they exist because of colonialism and the interventions of a colonial government. I don’t know if that changes the way you feel about them, but if it does, I wonder about the quality of that shift. What exactly has shifted? How has your opinion of them changed?

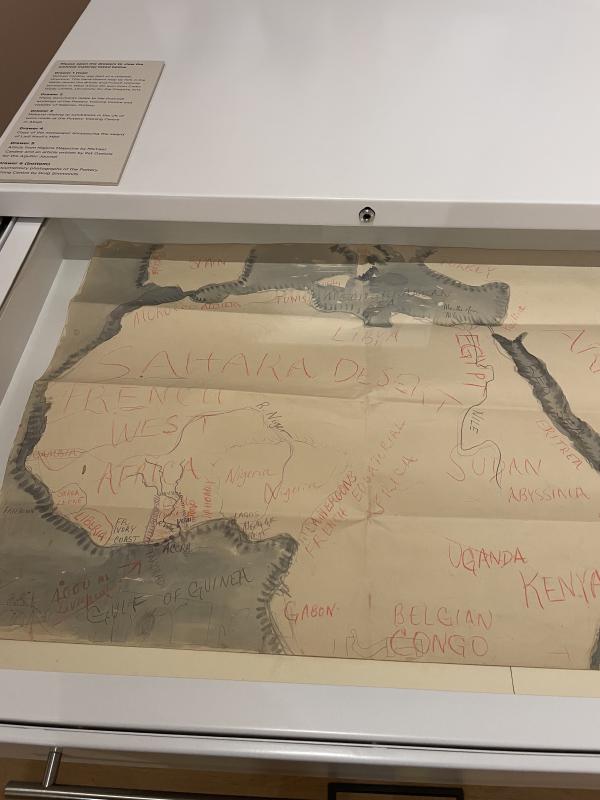

For me, as I read the wall texts and pieced this story together, I found myself becoming more and more clenched. But I’ll show you what really sent me. There’s a set of white archival drawers in the first gallery; if you go over and open them up, there are little newspaper clippings and magazine cutouts, old letters and stuff like that. The top drawer contains a big hand drawn map of the upper half of the continent of Africa. The paper cuts off the rest around ‘BELGIAN CONGO’ - this label is written in large red capital letters. The sea around the landmass is filled in with murky blue watercolour. In the upper right corner, the land joins up with the Arabian peninsula. It is labelled ‘ARABIA’ in the same scrawled red capitals. This map is hand drawn by Michael Cardew. Looking at this map made me feel woozy. I was being pulled in different, opposing directions. Michael Cardew was part of the machinery of colonialism. He was one man - yeah - but he was an active participant in a colonial government, an agent of this colonial government’s agenda. He intervened in the cultural history of a country that was ruled over, by force, acting on behalf of the colonial government he was a part of. But he also supported and facilitated Nigerian potters, gave them skills and resources, acted as a passionate representative. I don’t know! Maybe I’m being soft but this map is terrible and it makes me feel ill. It is charting a section of a continent that was carved up by European powers. It treats this landscape like it is territory to be conquered, ruled over, catalogued into submission.

And anyway, who was Michael Cardew to be training people up in industrial pottery techniques? Or to be pioneering a new understanding for Nigerian ceramics? The arrogance of that is astounding. It’s not like he came to Nigeria and taught people about pottery because it was unheard of and brand new, there was an existing culture and craft that he shaped into a hybrid form. The colonial government in Nigeria were seeking to make traditional ‘indigenous’ crafts on an industrial scale so it could be produced in bulk for export. It was about trade, and we know that trade has never been neutral. It is a loaded thing, colonialism runs hand in hand with capitalist expansion.

But if we’re really thinking about this, Michael Cardew isn’t the point. The pots on display are not made by Michael Cardew alone and it is also equally tense to get sidetracked by the white guy like he’s the only main character. Michael Cardew might have set up the Pottery Training Centre, but now it’s called the Dr Ladi Kwali Pottery Centre. Ladi Kwali was an acclaimed potter who made an enormous contribution to cultural history. If you head back through to the second half of the room, there are three large round pots on another low white plinth. These pots have a matte surface. They are round and swollen. They are all different shapes: one has a long neck, one has no neck (only a little protruding rim), the third flutes out a bit further like it is showing off. They are all different red-y orange colours, a mix of terracotta and burnt earth, pastel orange. They are dappled with an ashy grey gradient across them all - like ballooning planets, like Jupiter or the surface of some alien landscape from afar. If you get very very close, you might see them shimmer a bit, because there is a little granular kind of mineral glitter trapped in their surface. There are lines scratched into them all, running in different abstract patterns, perpendicular and modern or crisscrossing like crosshatching. The light just ripples off of them. The grey gradient blows across all three, billowing and webbed, light and cloudy. They were made by Magdalene Odundo - a ceramicist born in Kenya, but she now lives and works in Britain. She studied in Abuja with Ladi Kwali, took what she learned and ran with it - because after Ladi Kwali, there were other women too. It was’t really Michael Cardew that pioneered that new understanding in Nigerian ceramics, it was Ladi Kwali. She’s the one that sits in cultural history, at a meeting point of a complex web of lines running from person to person in a sprawling legacy. I don’t know if I believe this truly or entirely, but it is the closest I can get to a happy resolution.

It’s uncomfortable that a group of British people had such a prominent hand in shaping the landscape of Nigerian pottery and art history. Not just Michael Cardew, but there are other parts of Nigerian art history - and the art history of countless other countries that were once part of the British Empire - that have been treated by this intervention as a result of colonialism. It’s uncomfortable, but it happened. I am glad that I know about it, glad that I learned about it, hate that it happened, hate that I now have to think about it. Most of all, I hate that I haven’t been handed a point of resolution or closure. I don’t know what to do with the discomfort. I don’t know how to feel about any of this. It feels aimless. Or like the discomfort is immaterial or secondary. It’s not the point, it goes nowhere, this is just history. I guess that’s fundamentally the whole point, right? Colonialism was shit because it enriched Europe at the expense of literally the entire rest of the world. That happened, and is actually still happening - we are living in the world that colonialism built. But what now? What do we do now that we have said that? It hasn’t ended, it hasn’t stopped, it hasn’t become undone. It just is. And we all have to sit with that: knowing that acknowledging it is urgently necessary and also entirely pointless at the same time.

I think I’ll leave you here with that. Maybe that’s a bleak way to end this guided meditation, but I’d rather be bleak and honest. I’d rather tell you that there is no good ending and no neat way to square this all. If you’re physically in the room at York Art Gallery, then you can head through the doors at the back. There’s another room full of work by contemporary Black artists and ceramicists: Jade Montserrat, Julia Phillips, Phoebe Collings-James and Shawanda Corbett. Maybe they are working through some of that discomfort that we spoke about? Maybe they are negotiating a path towards resolution or closure in their work? I don’t know. But if you’ve listened to this episode of the podcast, let me know what you think of that. Every week on this podcast, we play a little game with our listeners. We post about the Sunday episodes on our instagram and twitter, so head to @thewhitepube on whichever one and leave a little pot emoji on the post. It’s just a weird little game, like an insiders club for everyone listening in. And if you have any thoughts about this podcast episode, any answers or additional thoughts that this episode prompted - whether it came from an IRL visit or a guided meditation visit - do let me know about those too. And I’ll see you next time - bye!

this text was commissioned by Mediale, on behalf of York Art Gallery. As usual, you can find details of all our lil jobs and bits of income on our accounts page, and it goes without saying that commission or not, we say what we really think.