Cameron Rowland, 3 & 4 Will. IV c. 73 @ the ICA

ZM

Emoji summary: 🥵 🦴 🔄

Many years ago, a clever clever friend of mine asked if political art can ever escape the shadow of its own spectacle. Within that one question, are a thousand more: what is political art, who’s defining which art is political, how does that spectacle get made, whose politic constitutes a baggage that must be escaped, n whose politic is assimilable into the dominant cultural landscape we find ourselves cast against? On n on. That is why it is such a clever question; it is a question that ~contains multitudes~. My first take-away from Cameron Rowland’s show at the ICA, is that I think it is able to escape the shadow of its own spectacle by pointing at that shadow and saying: ‘this is the work’, when ACTUALLY, the pointing is the work. I don’t think this makes sense just yet, but bear with me, I’ll explain.

The exhibition is titled < 3 & 4 Will. IV c.73 >, at first glance it feels unintelligible, but after like 5 seconds of googling, I realised it’s a legal/legislative code for an Act of Parliament. It’s formally called a citation, and each part of it represents/refers to a signifier that would allow you to place it within a frame of time/track it down in a public database/reference it. The Act of Parliament this code refers to is the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, passed through Parliament to abolish slavery throughout the British Empire. This is a clunky way for me to explain the title within a review; Rowland does a much better more nuanced job in the handout that accompanies the exhibition.

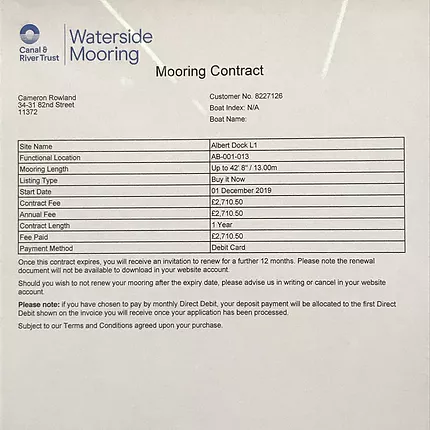

Throughout the years, both Gab and I have made a lot of noise about how we don’t read the press release. I took about 10 bolshy steps into the gallery before I realised and slunk back to the entrance to sheepishly grab it. It’s fat, carries a satisfying kinda heft to it; there’s an essay that acts as a primer, and then each work has a caption. The work itself, half of it is this collection of physical actual objects: a mahogany writing box, brass manillas, a gold two-Guinea coin, police car searchlights, the lease on a mooring in the Albert Dock in Liverpool. Alone, this half of the work, the physical tangible objects that are present, feel sparse across the gallery. It’s only through reading the booklet that you complete this interaction with the artwork; Reading becomes an integral part of Viewing, which then unfolds a series of conceptual n theoretical actions n implications. It’s a bit of a mad one but bear w me. Take the manillas for example. It goes like this: the manillas are placed in a way that is legible as contemporary art. In reading the caption, the manillas are understood as loaded objects, ‘as a one-directional currency, which Europeans would offer as payment but would never accept’. The ones on display are rentals, manufactured in Birmingham in the 18thC. They’re now grounded in the gallery (as aesthetic objects), the land (as native historical objects) and a socio-political history, each as spaces of relevance in this relationship of display. The caption situates the objects as functional, but now also as active: ‘Birmingham was the primary producer of brass manillas in Britain, prior to the city’s central role in the Industrial Revolution’; we can understand them as part of a transition that happened against a specific historical backdrop, not just as passive functional objects, but as objects that were participants in the process of expansion due to their production. The caption then describes the amplified scale in the affect of this action, quoting Eric Williams’ <Capitalism and Slavery>, in a description of “the triple stimulus to British industry” represented by these manillas; this stimulus was ‘provided through the export of British goods manufactured for the purchasing of slaves, the processing of raw materials grown by slaves, and the formation of new colonial markets for British-made goods’. The captions have a linear way of making clear specific things about the objects. As our example - the manillas are then, in this way, conceptually unfolded: as art-object, as currency, as historical object, native object, political, functional, active participant, product and then finally as representative. In this unfolding, these manillas arguably provide testimony, act as witnesses for an academic exploration that takes place on a more expanded scale in the main body of the opening essay.

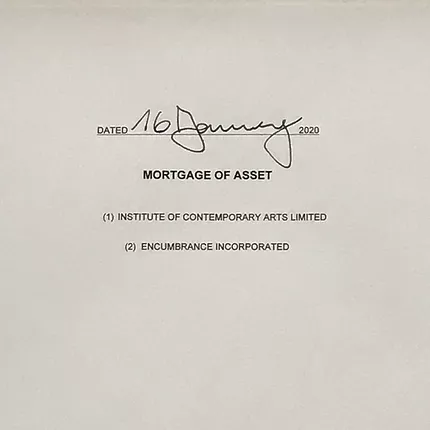

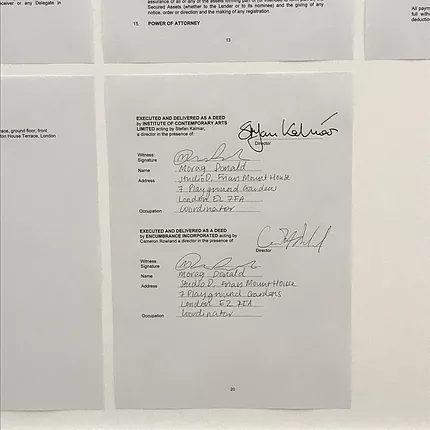

Upstairs is a similar vibe: 3 cattle brands, an electronic monitoring device (for probation, parole, detention), a probation order neatly framed like the Albert Docks mooring lease downstairs. Most of the wall in the upper gallery is taken up by mortgage contracts spread out across enormous frames. The doors of the gallery, the back door onto the street and the handrail going up to the first floor, are all listed as artworks; the mortgage contracts are for them. The caption explains that the doors and handrail are mahogany, a wood ‘felled and milled by slaves in Jamaica, Barbados, and Honduras among other British colonies. It is one of the few commodities of the triangular [transatlantic] trade that continues to generate value for those who currently own it.’ The caption continues, explaining that Carlton House Terrace, where the ICA is now, used to be George IV’s family residence (before he took the throne). He built the current terrace over the old house, ‘as a series of elite rental properties to generate revenue for the Crown Estate’. The ICA currently still leases the building from the Crown Estate; including the mahogany handrail and the doors. In mortgaging them, there’s also the commitment to not repay this loan, so Encumbrance Inc (the company that has issued this mortgage) technically owns the handrails and doors(? I don’t understand mortgages wow), or that this debt must effect the eventual value in the re-sale of the property, or the Crown Estate j can’t accumulate profit from them? The caption says it ‘constitute[s] an encumbrance on the future transaction of 12 Carlton House Terrace’, using the words ‘as reparation’. Although I can’t make out the specifics of what this mortgaging involves in a practical sense, I am very aware that this is still a real and tangible thing with or without my understanding; ‘the Crown Estate provides 75% of its revenue to the Treasury and 25% directly to the monarch’. There’s a significant intervention in this: Cameron Rowland’s work has quite literally diddled the Queen and the Chancellor of the Exchequer out of some money, while illustrating that the afterburn of the transatlantic slave trade is very very present in Britain - still hot to the touch, especially where these enormous institutions are concerned. This feels like a marked win, a stifled laugh out loud compared to the Tate’s heavily PR vetted and incredibly self-conscious statement about their association with slavery and the profits of it, that took a long time to say absolutely nothing at all, and (more importantly) was functionally useless in any material sense. <Encumbrance> as a work, is an action; the work isn’t the actual doors or the handrail, or the mortgage itself - the work ends up being this moment after the action/spectacle, the end effect of it, the shadow it has cast, the pointing to it. The work is the reparative win of the Queen & State not being able to profit off the products of slavery in the gallery, and maybe it’s just that the bar is underground! But I was still quite affected by that tangible feeling of Someone Having Done Something. It’s rare to see something slight and gestural, that has such a rippling wave, in a gallery with the formal considerations accounted for and seamlessly blended.

In a practical sense, as a way of experiencing an exhibition, by walking round and reading between object and text, this is quite incredible to me. I am enjoying it; if the white pube represents a way of writing about the embodied reality of being in a gallery, then in a very tangible n bodily way, this is an exciting exhibition. Because you’re at this sharp edge of so many things: theory, aesthetics, research and action/intervention. The work is incisive, precise, carried out with a kind of forensic detail that is mirrored in the writing. It is all citation, pulling from a wealth of study conducted elsewhere, outside of a gallery, but it is simultaneously conventionally beautiful as contemporary art goes, and politically rigid in its expectations of the viewer’s understanding (in a good way that allows for little lack of complicity). It’s ~concurrent~, a kind of synchronicity in the way it voices itself; at the time of writing I am currently reading Paul Beatty’s <the Sellout> that is heavy fiction around the racist carceral state & police brutality, and I’ve just read Imani Robinson’s essay <OBJECTS WHO TESTIFY> (published by PSS as part of Boundary + Gesture @ Wysing, curated by Taylor Le Melle), an essay about forensic aesthetics, the image of Blackness, and the place of testimony & speech between those points. Beyond myself and this coincidence in my reading choices, the voice of it sits alongside Kathrine Yusoff’s <A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None>, Saidiya Hartman (who’s part of the live program for this show), this text is already too long for me to name a million academics and thinkers and writers that have contributed to the landscape it sits in. What I mean to say is that this show is a beautiful, thoughtful, painfully precise rendering of all of this incredible thought around blackness and the after-image of slavery, what its conceptual psychic intellectual material economic social holistic legacy contains. All loaded into these points between object and text, aesthetic and thought.

I think there is a question for me about opacity within the subject of aesthetic. The show looks sparse at a glance, since half of it is contained in the handout; something that Eddy Frankel’s review for Time Out didn’t seem to have much time for (lmao). In his review, Eddy concludes; ‘But for something so interesting, so important, it misses the mark so badly. A couple of almost empty rooms and a dissertation don’t make for an engaging, affecting art experience. And would it have killed the ICA to give just a single explanatory paragraph to help viewers into the show? Could they not have laid it all just a little bit more bare? Instead, all of Rowland's work holds you at arm’s length, refusing to let you in. It’s the kind of academic, unyielding exhibition that makes people hate contemporary art. It feels like art for people with degrees; it feels like it’s saying: ‘If you don’t get it, it’s not for you, and that’s your fault, not mine.’… It’s elitist, and it stops people from engaging. Rowland has powerful ideas; they’re just expressed really weakly.’ I don’t want to make a fucking habit of calling white art critics idiots, but this seems to be the basis of my entire career at this point. I think it’s a bit weird to say all of that tbqh. To point to the entire history of black academic thought that this show actively pulls from, goes to great pains to unpack and illustrate as clearly and forensically as possible, and say ‘this doesn’t make sense to ~the public~’ is fucking rude, and quite loudly wrong to ask for an explanatory paragraph when they’ve given you an entire fucking publication that you can reasonably read cover to cover on the tube ride home if you’re honestly that pressed about it. In my humble opinion, it’s revealing that Frankel’s review tries to instrumentalise the idea of The Public against this work, while simultaneously never really defining who that public is. It feels like The Public he’s wielding is more of a construction, a stodgy monolith that looks overwhelmingly like him on a blown out scale, a weird unyielding lump that speaks in unison, in his voice - - because the public I care about, and continue to be in conversation with (100 black & brown people with a vague to intense interest in the arts) have and contain the capacity to understand this work. I have had conversations with uncles on the bus that amount to a cursory understanding of the theory this engages with. This show isn’t for white people to be affected in the way they want to be affected by ~political~ art, because clearly the expectations of this Great White British Public hinge on the work creating the exact spectacle that would render it assimilable and comforting, rather than the sticky jagged edged shape that it is. Maybe, as I said in my review of <you feel me_> @ FACT, there’s an issue with the expectation of a white critic being projected onto a black artist/curator. Maybe Whiteness has a fundamental problem, maybe it comes undone a bit when it can’t consume Black spectacle as easily as it wants to. Frankel says it himself, ‘It’s saying: ‘If you don’t get it, it’s not for you, and that’s your fault, not mine’’ and there’s absolutely nothing wrong with that! I will defend Black artists’ rights to opacity till my dying breath! And this is exactly that, imo. The work held the artist away from the work, instead the work was able to form legibility in action and theory rather than an embodied affectation. The artist is held obscured, the spectacle is slight and about the unfolding and wide-eyed realisation that maybe action has spilled over outside of the gallery, but in a way that primarily effects the State rather than the viewer. This question of opacity is still a valid one, but my gOD, it is not for the Eddy fucking Frankel’s of the art world to gesticulate around, not for him to offer jurisdiction over - reader, it isn’t even for me. If there is a gap in understanding and engagement, then there is the potential for it to be closed within the space of the live program that’s part of this show. It’s printed on the back with no context, just the names of some thinkers/writers/people and dates. I’m writing this before any of them have happened (slightly unhelpful I know), but there remains the potential for the live program to consist of a third and equal part of the Work itself (something that only makes this show even more exciting, since tbqh live/events programs rarely ever take a significant/prominent role in the actual experience of an exhibition).

The Time Out review, for me, sealed the deal. I love this show because Eddy Frankel and all the other boring loud white men of Culture don’t understand it. It uses a completely different lexicon, a different rubric and set of measures for itself, it refers to a different way of working and demands different complicities for you to meld with it in a satisfying way; in Frankel’s fury at it, it is clearly proving itself to be unassimilable, despite the fact that it consciously, carefully looks like fucking contemporary art. It is complex, sticky, this precise incisive thing that unfolds from itself and contains the potential to be one of those shows that you’re reminded of 3 years later, when you read something entirely new into or from it. I have put off writing this text over and over, waiting till I could find someone to speak about it to, so I could settle my thoughts before starting. I have DMed friends, harassed Gab as my captive audience; this is a show you go to alone, but not one that you process alone. I believe it must be thought about collectively, or it won’t work. It’s discourse, baby.

Cameron Rowland's <3 & 4 Will. IV c. 73> is on @ the ICA until 12th April. You can find the live program on the exhibition page, here. The exhibition pamphlet is here.

This text is one of the six we are producing as part of our time as critics-in-residence @ the ICA in 2020. For more information about the shape of this residency & what it entails, pls see the ICA residency page.

Pacotille, 2020

Brass manillas manufactured in Birmingham, 18th century; glass beads manufactured in Venice, 18th century

103 × 68 × 3 cm (40 ½ × 26 ¾ × 1 ⅛ inches)

Rental

European goods traded for enslaved people were manufactured specifically for this purpose. Manillas were used as a one-directional currency, which Europeans would offer as payment but would never accept. The Portuguese determined the value of slave life at 12–15 manillas in the early 1500s. Birmingham was the primary producer of brass manillas in Britain, prior to the city’s central role in the Industrial Revolution. The British also used cheap beads acquired throughout Europe to buy slaves. Eric Williams describes the “triple stimulus to British industry” provided through the export of British goods manufactured for the purchasing of slaves, the processing of raw materials grown by slaves, and the formation of new colonial markets for British-made goods. The production of European goods for the slave trade supported domestic manufacturing markets. British trade in West Africa was understood to be nearly 100% profit.

What renders the Negroe-Trade still more estimable and important is, that near Nine-tenths of those Negroes are paid for in Africa with British Produce and Manufactures only. . . . We send no Specie or Bullion to pay for the Products of Africa, but, ’tis certain, we bring from thence very large Quantities of Gold; . . . From which Facts, the Trade to Africa may very truly be said to be, as it were, all Profit to the Nation.

Goods produced for the trade of slaves, which carried nearly no value in Europe, were called pacotille. Pacotille translates from French to English as “rubbish.”

1 A. H. M. Kirk-Greene, “The Major Currencies in Nigerian History,” Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria 2, no. 1 (December 1960): 146.

Eric Williams, Capitalism and Slavery, 2nd ed. (1944; repr. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1994), 52.

Malachy Postlethwayt, The National and Private Advantages of the African Trade Considered, 2nd ed. (London: John and Paul Knapton, 1746; London: William Otridge, Bookseller, 1772), 3. Citations refer to the Otridge edition.

Marie-Hélène Corréard, “pacotille,” in Pocket Oxford-Hachette French Dictionary: French-English (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 594.

Cameron Rowland

Credit, 2020

Gillows mahogany writing box, late 18th century

55 × 55 × 12.5 cm (21 ⅝ × 21 ⅝ × 4 ⅞ inches)

18th-century transatlantic credit was built on instruments of future repayment and loss prevention, including but not limited to promissory notes, bills of exchange, mortgages, and insurance. The development of paper notes as the medium of exchange was necessary for transatlantic communication and accountancy.

Writing boxes were used to carry correspondence and supplies as well as to provide a mobile writing surface. They allowed for written communication while traveling domestically and internationally.

Mahogany was used for shipbuilding by the Spanish and the British in the 17th century. Mahogany imported to Britain from Jamaica, Barbados, and Honduras, among other British colonies, was felled and milled by slaves. It was used extensively by furniture makers serving the upper-class as well as those targeting the middle-class such as Gillows. Gillows was founded in Lancaster and known for the quality and affordability of its products. Rathbone & Sons was one of its primary mahogany timber suppliers.

Joseph E. Inikori, Africans and the Industrial Revolution in England: A Study in International Trade and Economic Development (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 361; Craig Muldrew, “‘Blunderers and Blotters of the Law?’ The Rise of Conveyancing in the Eighteenth Century and Long-Term Socio-Legal Change,” in Law, Lawyers and Litigants in Early Modern England: Essays in Memory of Christopher W. Brooks, ed. Michael Lobban, Joanne Begiato, and Adrian Green (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 229–53.

C. D. Mell, “True Mahogany,” U.S. Department of Agriculture Bulletin No. 474 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, 1917), 9.

The “age of mahogany” expanded as “[T]he increasingly great trade and possessions in the West Indies encouraged the importation of mahogany, which after 1733 was shipped here in enormous quantities.” Percy Macquoid, A History of English Furniture: The Age of Mahogany (London: Lawrence and Bullen, 1906), 48–49.

Susan E. Stuart, Gillows of Lancaster and London, 1730–1840: Cabinetmakers and International Merchants,A Furniture and Business History: Volume 1 (Woodbridge, U.K.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2008), 16.

Susan E. Stuart, “Gillow Family,” in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, revised 26 May 2005), https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/67318.

Adam Bowett, “The Jamaica Trade: Gillow and the Use of Mahogany in the Eighteenth Century,” Regional Furniture 12 (1998): 22.

Cameron Rowland

Guineas, 2020

Two-guinea piece, 1664

3 × 3 cm (1 ⅛ × 1 ⅛ inches)

King Charles II founded the Company of Royal Adventurers Trading to

Africa in 1660, the year of the Restoration of the monarchy.

The company was renamed the Royal African Company in 1672. It was structured as a public-private company governed by the King’s brother James, Duke of York. James continued to govern the company during his reign as King James II. The Royal African Company was created to compete with Dutch transatlantic trade; to provide slaves to English West Indian colonies; to provide revenue directly to the monarch, allowing the King financial independence from Parliament; and to provide gold for the country.

In 1663, “as a further means of encouragement Charles II ordered all gold imported from Africa by the Royal Company to be coined with an elephant on one side, as a mark of distinction from the coins then prevalent in England. These coins were called ‘Guineas.’” The coins functioned both as currency and to increase the prestige of the company in England. The elephant with a castle on its back was the logo of the Royal African Company. Between 1675 and 1688, the Company supplied gold for an average of 25,000 guineas per year.

The Royal African Company’s gold trade was pivotal in England’s shift to a monetary system based on the standard value of gold. As Master of the Royal Mint, Isaac Newton shifted the country to a de facto gold standard in 1717, which was officially adopted in 1816. Britain used the gold standard until 1931.

William A. Pettigrew, Freedom’s Debt: The Royal African Company and the

Politics of the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1672–1752 (Chapel Hill: The

University of North Carolina Press, 2013), 23.

Pettigrew, 22–26.

George Frederick Zook, “The Royal Adventurers in England,” The Journal

of Negro History 4, no. 2 (1919): 153.

Pettigrew, 30.

Angela Redish, “The Evolution of the Gold Standard in England,” The

Journal of Economic History 50, no. 4 (December 1990): 789–90; David

Kynaston, Till Time’s Last Sand: A History of the Bank of England,

1694–2013

(London: Bloomsbury, 2017), 42.

Cameron Rowland

probability of escape, 2020

Police car searchlight

50 × 15 × 29 cm (19 ⅝ × 5 ⅞ × 11 ⅜ inches)

“[I]f any poor small free-holder or other person kill a Negro or other

Slave by Night, out of the Road or Common Path, and stealing, or

attempting to steal his Provision, Swine, or other Goods, he shall not

be accountable for it; any Law, Statute, or Ordinance to the contrary

notwithstanding.”

– ‘An Act for the Governing of Negroes,’ Barbados, 1688

“[I]f any person shall kill a slave stealing in his house or

plantation by night, the said slave refusing to submit himself, such

person shall not be liable to any damage or action for the same; any

law, custom or usage to the contrary notwithstanding.”

– ‘An Act for the Better Ordering of Slaves,’ South Carolina, 1690

“A citizen may arrest a person in the nighttime by efficient means as

the darkness and the probability of escape render necessary, even if the

life of the person should be taken, when the person:

(a) has committed a felony;

(b) has entered a dwelling house without express or implied permission;

(c) has broken or is breaking into an outhouse with a view to plunder;

(d) has in his possession stolen property; or

(e) being under circumstances which raise just suspicion of his design

to steal or to commit some felony,

flees when he is hailed.”

– SC Code § 17-13-20 (2012), South Carolina, current statute

Cameron Rowland

Encumbrance, 2020

Mortgage; mahogany handrail: 12 Carlton House Terrace, stairwell,

ground floor to first floor

The property relation of the enslaved included and exceeded that of chattel and real estate. Plantation mortgages exemplify the ways in which the value of people who were enslaved, the land they were forced to labor on, and the houses they were forced to maintain were mutually constitutive. Richard Pares writes that “[mortgages] became commoner and commoner until, by 1800, almost every large plantation debt was a mortgage debt.” Slaves simultaneously functioned as collateral for the debts of their masters, while laboring intergenerationally under the debt of the master. The taxation of plantation products imported to Britain, as well as the taxation of interest paid to plantation lenders, provided revenue for Parliament and income for the monarch.

Mahogany became a valuable British import in the 18th century. It was used for a wide variety of architectural applications and furniture, characterizing Georgian and Regency styles. The timbers were felled and milled by slaves in Jamaica, Barbados, and Honduras among other British colonies. It is one of the few commodities of the triangular trade that continues to generate value for those who currently own it.

After taking the throne in 1820, George IV dismantled his residence, Carlton House, and the house of his parents, Buckingham House, combining elements from each to create Buckingham Palace. He built Carlton House Terrace between 1827 and 1832 on the former site of Carlton House as a series of elite rental properties to generate revenue for the Crown. All addresses at Carlton House Terrace are still owned by the Crown Estate, manager of land owned by the Crown since 1760.

12 Carlton House Terrace is leased to the Institute of Contemporary Arts. The building includes four mahogany doors and one mahogany handrail. These five mahogany elements were mortgaged by the Institute of Contemporary Arts to Encumbrance Inc. on January 16th, 2020 for £1000 each. These loans will not be repaid by the ICA. As security for these outstanding debts, Encumbrance Inc. will retain a security interest in these mahogany elements. This interest will constitute an encumbrance on the future transaction of 12 Carlton House Terrace. An encumbrance is a right or interest in real property that does not prohibit its exchange but diminishes its value. The encumbrance will remain on 12 Carlton House Terrace as long as the mahogany elements are part of the building. As reparation, this encumbrance seeks to limit the property’s continued accumulation of value for the Crown Estate. The Crown Estate provides 75% of its revenue to the Treasury and 25% directly to the monarch.

Cameron Rowland

Society, 2020

Cattle brands

90 × 13 × 11 cm (35 ⅜ × 5 ⅛ × 4 ⅜ inches)

Rental

Christopher Codrington was a Barbadian planter whose book collection formed the Codrington Library at Oxford. Codrington died in 1710, leaving his three plantations in Barbados to the Church of England. The Codrington plantations were operated by the Church to fund the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts. Enslaved people on the Codrington plantations were branded with the word “society.”

The word chattel was derived from “cattle” as the property relation of livestock was expanded to refer to all moveable property.

Cameron Rowland

Mooring, 2020

AB-001-013

William Rathbone and Sons was a timber merchant company founded in Liverpool in 1746. “[T]he foundation of the Rathbone fortune and business was built on the Africa slave trade.” During the 18th century, they imported timber felled and milled by slaves in the West Indies and operated a number of trading ships that sailed to West Indian colonies as well as the Southern States of America. Rathbone and Sons’ yard occupied a large portion of the Liverpool South Docks. Rathbone and Sons supplied timber for slave ship builders in Liverpool until at least 1783. These ships carried enslaved black people who were sold in the West Indies and in British North America. Ships built in Liverpool also carried the slaves who were sold on Negro Row at the Liverpool South Docks.

Liverpool built the world’s first wet dock in 1716, allowing cargo ships to dock directly at the port. By 1796, Liverpool had built 28 acres of docks.

Liverpool’s proximity to Ireland also not only facilitated a profitable trade, but provided a relatively safer route that allowed Liverpool ships less chance to be captured by French privateers. Additionally, the copper and brass manufactures in Lancashire and Ireland allowed for local companies that manufactured African trade goods such as manillas to carry on a prosperous export trade, further giving Liverpool a competitive edge. The relationships forged with nearby merchants not only helped secure trade goods, but also valuable credit terms.

In 1784, Rathbone and Sons imported the first consignment of raw cotton to England from the United States. From this point, they became stated abolitionists and free trade advocates. The abolition of the “West Indian monopoly” on the import of goods to the British Isles would allow for the expansion of U.S. cotton trading. Liverpool became the primary port of 19th-century cotton importation to England. Rathbone and Sons imported American cotton to Liverpool through the American Civil War. The company continues to operate as the investment and wealth management firm Rathbone Brothers Plc.

The mooring at the Albert Dock: AB-001-013 is on the former location of

the Rathbone warehouse.

This mooring has been rented for the purpose of not being used.

Jehanne Wake, Kleinwort Benson: The History of Two Families in Banking

(New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 15.

Wake, 16.

Adam Bowett, “The Jamaica Trade: Gillow and the Use of Mahogany in the

Eighteenth Century,” Regional Furniture 12 (1998): 22.

Wake, 16.

Eric Williams, Capitalism and Slavery, 2nd ed. (1944; repr. Chapel

Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1994), 52.

McDade, 1094.

Eleanor F. Rathbone, William Rathbone: A Memoir (London: Macmillan and

Co. Limited, 1905), 11.

Wake, 15, 31.

Sheila Marriner, “Rathbones’ Trading Activities in the Middle of the

Nineteenth Century,” Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire

& Cheshire 108 (1956): 118.

Cameron Rowland

Behavioral Intervention, 2020

Officer monitor for probation, parole, detention

Electronic monitoring is used to track people. In the U.S., it is often a condition of probation, parole, home detention, and release from immigration detention. It is described as an alternative to incarceration. It is legally termed “partial confinement.” Electronic monitoring imposes curfews stipulating when the person being monitored may and may not leave their home, and exclusion zones stipulating where they can and cannot go. Electronic monitoring in the U.S. rose 140% between 2005 and 2015. If the terms of electronic monitoring are violated, the person being monitored may be “fully confined” in prison.

The officer monitor manufactured by BI Incorporated is “a portable, handheld receiver that detects the presence of HomeGuard or TAD bracelets from several hundred feet away. It enables officers to conveniently monitor clients from outside a home, work, school, or any location.”

BI Incorporated provides Behavioral Interventions® services. It is a GEO Group company.

“Drive-BI®: Enhanced Monitoring in a Portable Package,” BI Inc., accessed January 14, 2020, https://bi.com/products-and-services/drive-bi-radio-frequency-monitoring-device-remote-location-technology/.