Frank Bowling: The Possibility of Paint are Never-ending @ Tate Britain

ZM

Emoji summary: 🌩 🌍 🕳

I feel like my taste in art moves seasonally, Like with food I want chunky soup in Winter, big loaves of bread & pav bhaji with buttery lil bun bois; but I only drink Fanta when it’s hot, my portions shrink n my food gets spicier. I only seem to like paintings in the Summer, I only have time for them when it’s hot and the sky is glassy blue. I enjoyed Frank Bowling @ Tate Britain with that as the limit, in a way. I enjoyed watching a painter’s life unfold, moving from room to room with incremental change. I can’t knock this show for being a retrospective; it just was, that was the format, limitations & all. I think the limits mean something when an artist’s work was burning and urgent, however. This is a review where I wish I cared about research, knowing an artist’s practice inside out. I wish I could muster up the will to speak with traditional authority.

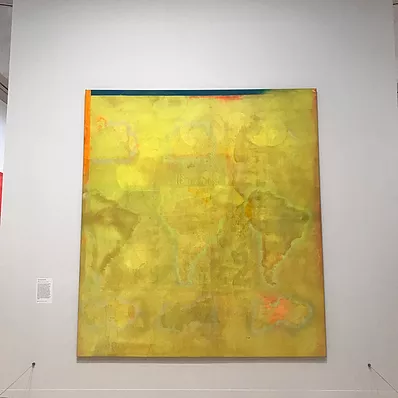

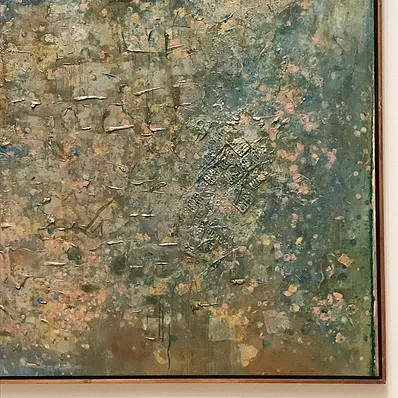

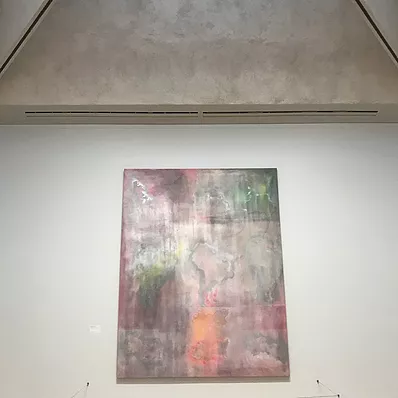

To speak briefly about the works, it was beautiful to watch this practice unfold, feel the elements at play washing over me. Frank Bowling has been consistent; painting every day, even now, taking an image and stripping it, pulling it apart, deconstructing it into oblivion and reconstructing it in its dismantled parts. The reoccurring image of Bowling’s Variety store, an outline of the island of Guyana [edit: apologies! Guyana is not an island, it's on the mainland of S America. My apologies & thank you for the correction!], the continent of Africa as a symbol n image both. It is a fascination with image & repetition that I share; what happens when you do up Ready Steady Cook & make yourself redeploy the same item over and over, create a limit if only to try to burst beyond another one further in the distance. For me, this obsession with image and repeating through a stickiness to process; seeing it in full technicolour kinda made me appreciate abstraction in a way I never had before. Bc isn’t that abstraction as a verb? Or the essence of abstraction in and of itself? To make something deteriorate until it loses all its ties to meaning or representation etc etc on & on. I think I respected the practice of it for the first time. Or the idea or premise of it? Abstract stuff has always been there just as a given, and I understood it but I never actually felt it until now.

I think people cleverer & more invested in a canonical or historicised view of art (over my experiential, at times esoteric view) have said this before me, but wow I literally deeped it in this show: the contributions of Black artists to the practice/concept/history/whatever the fuck it is// of abstraction is often obliterated. Why is that? Why is blackness not literally enmeshed within the very fabric of abstraction? I worry I might be speaking beyond the remit of my agency as a non-black poc here, but I think they both feel aligned. Blackness is unviewable by the white spectator. The white spectator simply does not have the range to see blackness for what it is, isn’t that basic Fanon? Whiteness sees only tropes, never humanity, only reduction, never life. Whiteness is incapable of understanding or rly truly acknowledging the humanity of black people because race has been constructed, and so many layers in between, to obscure it; and blackness is thrust further into an opacity, or an unknowability. Isn’t that abstraction? Have I got it very twisted? I am very much throwing this out there as a soft thought that only rly occurred to me as I was walking round; I haven’t had the time to bounce it around other people’s thoughts. Pls feel free to @ me on twitter, I am committed to chewing through this one, so any thoughts youse have are welcome.

Maybe I’ve never really respected the idea of abstraction properly until now because it’s always been a placeholder for lack; an absence. Where whiteness has functionally been synonymous with a dearth, scarcity or a vacuum free of social or political meaning; where there’s nothing to refer to; maybe I finally felt something bc there was actually something to grab on to? Maybe I was finally seeing what abstraction looks like when it’s not obscuring an emptiness, but rather an abundance, that is partially hidden from me also (!). But Bowling’s paintings had an energy, and a fullness that I found really enjoyable. The work was bursting with something, and I enjoyed spending time with the paintings in the hope that I’d be able to pull at the edge of that. They were exceedingly good company whether I reached clarity on that or not (narrator: reader, she did not).

I think this ~pseudo philosophical~ wannabe Greenberg chat aside, I also see concrete value in the more tangible politics of the show itself. Oscar Murillo pointed out that the fact that this was Bowling’s first major show in the UK was absolutely ridiculous. That he has been so systematically overlooked is not surprising to any one who’s experienced the art world as a person of colour! We only need to refer to Lubaina Himid’s career trajectory, that the Turner Prize came decades too late; or to look smaller by paying attention to what black and brown makers are saying now, whether emerging or established. There is, as Oscar Murillo pointed out, a systematic, structural leak. From the top to the bottom, the problem is one we’ve described (here, here & here) and tried to offer solutions to help do better. The problem is that the institution does not benefit from doing better. Murillo pointed out that ‘The institution [the Tate] is using tokenism and instrumentalising the moment to highlight this artist, but is also incredibly failing at it.’ I think the Tate, incredibly, took this to mean something completely different to what was said (?) Because Elena Crippa (the curator of this show) said: ‘All his life—through his work and his writing [Bowling] rejected being categorised or pinned down as being either a black artist belonging to the Windrush generation or anything else. And I truly believe that what the work does is speak about multiplicity, and the beautiful works, produced over six decades, do the work themselves.’ Alex Farquharson, the director of Tate Britain, and owner of the single most ridiculous surname since Rees-Mogg, said more of the same, ‘Frank Bowling has always refused to be defined by restrictive labels and has pursued forms of expression which are nuanced and open-ended. We worked closely with the artist throughout the process of making this major exhibition…’ That seems all well and good, characterisation of valuable context as ‘restrictive label[ling]’ aside, I think until you actually see the show. For me, it feels like something that could perhaps, for some people, be explained away by some vague gesticulating around what a retrospective is, what it does; that it’s meant to be a kind of whistle-stop tour of a lifetime of work, an artists’ greatest hits as well as the rap genius play by play of the lyrics. But I think if you pay closer attention to the patterns through which the Tate programme artists of colour within their main exhibitions, it feels like Murillo is prodding at something under the surface quite clearly. The Tate wouldn’t know the difference between what constitutes valid context and what flies into the realms of wild tokenism if it wore a name label on its forehead. This feels all the more pertinent considering that Frank Bowling himself said, ‘I waited for such a long time for [the exhibition] to happen that when it was announced, I was told that it would be an exhibition that I wanted, but I quickly found out that once more the [difference in the] language between myself and people like the Tate. I hear one thing and they think they've said something else. It turns out it's going to be a Tate show and not mine.’ I think this speaks to an uncomfortability I felt, a taught tense rope strung through the way the exhibition was framed. Where it was meant to be blindingly political, blistering through context, the framing fell flat. Where image was image and repetition was process and progress, it felt tokenistic - like some curator in a back room was absolutely rubbing their hands with glee over the idea of a whole Windrush gen artist painting the outline of Guyana. It was inversed, imo. For lots of poc, our skins are not a burden or a driving desire, they are just a fact. It is a fact that informs our experience and our experience informs a multitude of things, not least how we navigate the politics of Making a Thing. The nuance between the former and the latter state has been something the Tate has consistently misunderstood in all my years of visiting. It speaks to the fact that so much of the decision-making at the Tate is done by white people who only interact with people of colour when they’re at the Post Office or the takeaway. It speaks to the fact that the Tate is a closed loop at the best of times. This isn’t really about diversity, more about understanding and willingness to engage and listen to an artist, to treat them as a valid agent within the process of exhibition-making. I wonder if this situation would’ve happened with a white artist at a similar level.

I feel a yearning for more & simultaneously am completely unable to identify it. For me, I’m not sure the politics of the show behind the scenes is something I want to end on for this review. Yes, there is a very serious void, the Tate are responsible for that. But my experience of Frank Bowling’s work was not an experience of lack or that void. I think, I think, I saw a glimpse of that More within the work itself. I felt fullness - which makes the politics all the more visibly ridiculous - but which is also a lasting, dwelling feeling that I am still carrying with me through this.