Jasleen Kaur, Gut Feelings Meri Jaan @ Touchstones

ZM

Emoji summary: 🤕✨🪃

I have never cared for archives. I think some people have this switch flipped in their brains, which means they deeply understand the need to catalogue history. The archive has an endless magic for them. Maybe it’s because I am from a city that drives only forwards (on and on and on - high rises, new builds, urban regeneration), maybe it’s because there is an optimism in believing that the future is where the magic’s at. But I don’t see the point in looking back for the sake of it. I don’t see the value in becoming transfixed by the past, holding on to where we all came from. I only want to glance back so I can judge how far we’ve got left to go. I want to be more preoccupied with the future.

This week’s review is of Gut Feelings Meri Jaan, a show up at Touchstones in Rochdale. Jasleen Kaur is an artist who has been working with a group of women and gender non-conforming people local to Rochdale, from the Pakistani, Bengali and Punjabi diaspora. This group has been meeting since before the pandemic, and then on zoom in lockdown. They started looking at the contents of the local history archives at Touchstones. All these sessions spent in each others company, sharing and exchanging, telling each other stories and listening. Gut Feelings Meri Jaan is the product of this collaboration. It is the front end of something deeper, maybe darker too. It is also not the point.

The show is made up of three sets of films, shot by one of the group members, Alina Akbar. In the gallery they’re all spaced out in their own little viewing areas.

One film shows the group, six of them, lined up in a row and side-on to the camera. They’re wearing shiny salwars and leggings, all standing on those little step machines. They’re out in a field and you can hear cows and traffic occasionally. But they hold neat scripts, flip through and take turns reading these anecdotes. Like little frescoes, snippets of bits, stories.

One reads: I grew up in the 80s with the National Front marching and being really fearful for our lives, you know, things like our windows being put through.

Another, younger, reads: Your generation had the National Front, mine had the EDL. Like, I can remember people, all the boys getting together to go and fight the EDL and it’s not stopped. My generation’s definitely seen it.

Cows roam over the hilly fields in the background. The wind blows their hair and the fabric of their salwars into little waving flutters, as they step step step and read in turn. I watch from a chunky armchair, upholstered in the same green shiny fabric as some of the salwars. When I press my fingers into the surface, an iridescent rainbow smudge glares out at me. At times, I squirm. Because I want history to feel like it is progressing, like things can only get better. Wouldn’t that be so nice, if the liberal promise of linear progression was a true happily ever after? But these stories tell me that history moves in circles, history is stuck.

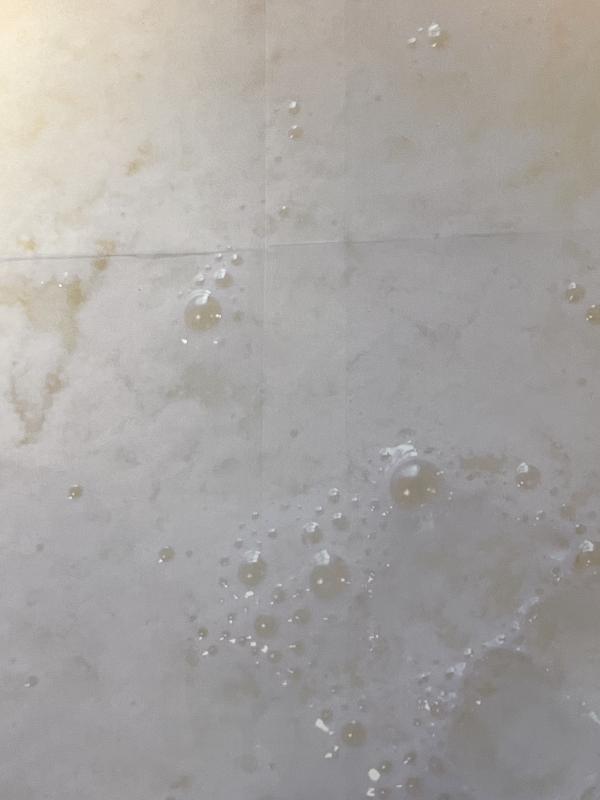

Next up, three films all clustered together. In one, members of the group wipe down the gallery steps with yoghurt. There’s a big bucket of it between them, 10kg of Henna Fat Free Natural Yoghurt. It’s all over their hands, in lumps and clumps as they smear long white streaks across the grey steps. In another, members of the group wipe the same yoghurt across a statue just across the road from Touchstones. I passed it on my way there, a tall imposing lump on the edge of a park. The statue is of John Bright; a Victorian mill owner, politician, a Quaker with Radical & Liberal politics (I unclench a bit, but not entirely). The yoghurt is watery as they wash it over the base of the statue, dipping their hands into large metal bowls. The yoghurt runs down the surface, only leaving a pale smudge against the mossy weatherbeaten stone. In the last video, two members of the group are in the middle of a narrow street. One is on a stool, hair down and back. The other applies the yoghurt through her hair, gentle but thorough. In all of these films, the members of the group are wearing the same shimmering salwars. I watch all three at once. My eyes bounce between them. They’re mounted in a cluster, on a wall covered with a large photograph: a close up shot of the top of a bucket of yoghurt. The surface is milky white and bubbly. It reminds me of being sick, seeing something return to the air half digested and covered in bile. I watch from a beige leather massage chair, vibrating on wave mode across my shoulders, hips, thighs, shoulders, hips, thighs.

The last video is of three group members hidden between the stacks of an archive. Nestled close between shelves and bundles of paper, wrapped in ribbons and in boxes. The person at the back reads aloud from a document: it’s from 1987, it tells the story of a man who came from India to Kenya to the UK. It’s the same route my mum came, both were born British citizens out in the colonies. There are loose leaves of paper scattered over the floor. I don’t want to spoil the ending, but that man didn’t have a nice time once he arrived. He doesn’t live happily ever after. I don’t think any of us ever do, y’know. Not even when we think the story’s over. The reading has ended and the three figures are silent. One rips a chunk out of the document. The tearing sound feels amplified and careful. In silence they sit and pick little mouthful sized bits of paper, carefully raise them to their lips, open and chew slowly. One takes a bite directly from a corner of a page. They continue to read in turn, munching and crinkling as they go.

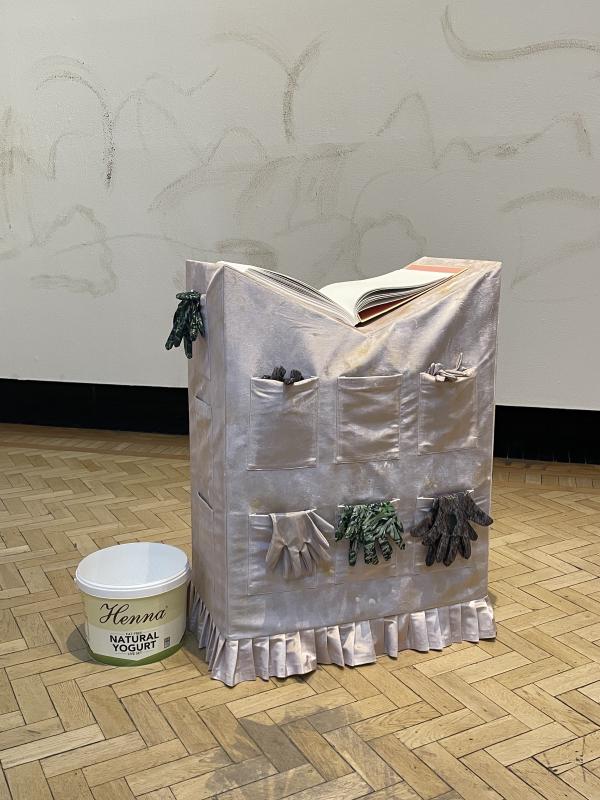

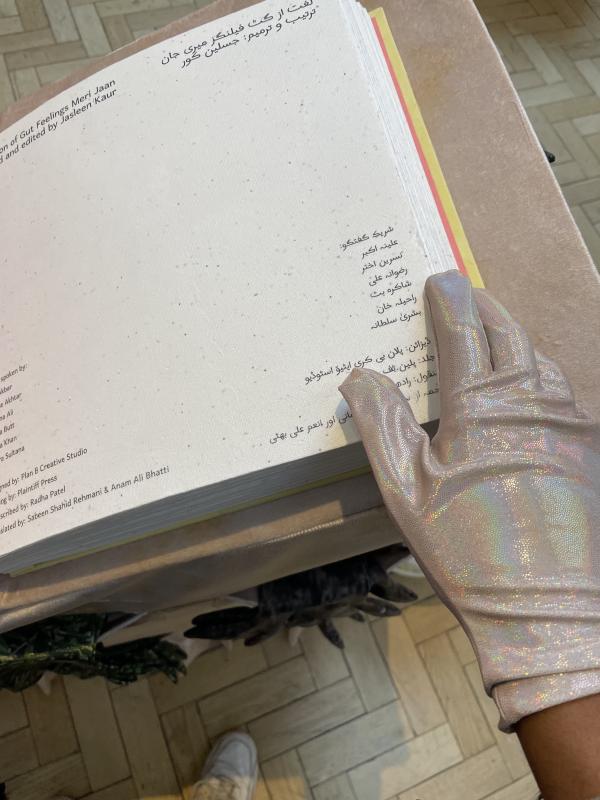

In the gallery, these films are placed along the walls. You watch them from seats in the middle, facing out. As I sit on the big green shimmery sofa, the wall swims into focus properly and I realise that there are little brown muddy lines raked along the wall. Little flourishes and swoops. I don’t think it’s writing or a drawing, but I couldn’t say for sure. Off to one side there’s a small stand with a large book. The stories read aloud by the group are all printed out nice, in English and Urdu side by side. The stories told in the field and in the archive. It’s printed on seed paper, this thick fibrous material with little seedy flecks embedded deep within. As you turn each page, it feels heavy and sombre. But it’s not all serious; there are little gloves made of the shimmery salwar fabric stuffed into little pockets sewn into the stand. Turning the pages would feel like an act of reverence without the gloves, but with them on it all feels very showbiz and glamorous. Apparently this book is going to be read aloud and buried in a ceremony at a community centre nearby. The seeds will grow.

Between these three sets of films, this show, the group presents a front. This is their output. They did the work of digging and discovery in the Touchstones archive, they unpacked it all, and now this show is like a reflex or a response. Everything that unfolds in the films and within the gentle container of the gallery feels measured and timed. They present us with a tight logic of specific action. Yoghurt as a symbol or sign - literally a living culture being wiped over monuments and buildings, and then pressed into contact with bodies (hair). The empty 10kg yoghurt bucket sits in the gallery, next to the book on its stand. It’s like it is waiting. The group eat the documents they read aloud in the archive. Not as an act of destruction, but a kind of reclamation. They reintroduce this material to the interior world, the body claims it through the act of digestion. Actually digestion holds a double meaning too, because by reading these things aloud they give these stories and truths a kind of air. They hold them up to us, viewer and group, we process them together. So digestion becomes a way of rationalising these heavy heavy things.

The only thing is, I think this exhibition is sleight of hand. It is a kind of illusion, it isn’t the point. It’s really good stagecraft: the costumes, the rituals and the aesthetic choices. From the rolling fields, the plastic covers on the chairs, the empty bucket of yoghurt, the step machines. It is all the front end of a metaphor. Jasleen and the group have spent all this time just speaking and being together, they’ve forged connections and shared stories. Throughout that process, they’ve looked back and figured out where they are. The group spans generations, this connection is a kind of conspiracy because it means they can measure their relationship to history, the archives, to monuments and all the other bits of large scale culture that make up this silly country. I don’t know what those conversations were, I don’t know what was shared, and I don’t know anything about the quality of the relationships that make up the group. What I do know is: the exhibition isn’t the point, the group is. They have undergone a change. In sharing with each other and processing this material, they now have a renegotiated relationship with history itself. And that is where I think it gets dark.

I don’t know how to say this without sounding like a pessimist. History is stuck, or we are stuck when history says we should be moving. Either way, something about the loop we’re in feels like running in a dream (when your limbs are sticky and slow and the bad guy’s close behind you). I don’t want to look back, because we should be going forwards but there’s nowhere to fucking go. What is forwards? I don’t know what is to be gained from renegotiating our relationship with history, by looking back into the archives to see where we came from. Because looking at the past and looking at the present, all I can see is that we haven’t really gone anywhere. As aesthetic choice and ritual gesture, this show was beautiful. But Gut Feelings Meri Jaan sat heavy with me because I think the best we can do is go limp, collapse into this country’s bad vibes and try and dig out some happiness amongst it all. Tbh maybe that’s the content of those hidden conversations. Maybe that’s the point.

Gut Feelings Meri Jaan was commissioned by UP Projects in partnership with Touchstones Rochdale. It is on at Touchstones in Rochdale, it closes on 13th Feb (so the day I’m posting this :S) but you can peep the trailer for the films here.