Manifesto, Ane Hjort Guttu

Emoji summary: 👩🏾🎨🖼🎨

I remember when I told my parents I wanted to go to art school. My Dad started ringing me every day, because he thought I was In Crisis and acting out. My Mum would sit me down at the dinner table and ask me to think about this all reasonably and practically. She took me to go see a religious man, who told me the stars weren’t in the right place for this decision. ‘What’s the PLAN??’ they’d both ask. To them, art school was somewhere you went to avoid making plans. It was Dreamland, a chaotic void, an abyss.

I went anyway, because I hate being told what to do. I applied to Central St Martins because (I swear to god) that’s where MIA went. I wanted newness to just pour out of my open mouth, like I was being violently and uncontrollably sick. If art school was a chaotic void, I wanted to enter that void with my hands in the air, screaming.

St Martins was a weird place. I still look back and feel like it was a fever dream, because those were the wildest 3 years of my life. It had its quirks, and they formed me. Like… Every month or so, someone would start a rumour that Kanye West was going to do a secret gig in the Platform Bar. I remember the day he walked around on a tour of the building, and everyone lost their fucking minds. I remember that everyone would keep an eye out for Antonio Banderas because he was doing a remote-learning MA, and everyone thought he came in at the weekends to use the library. I remember the drama students walking into the canteen barefoot, and Gab whispered to me ‘if they’re late back to rehearsal they get sent home for the day, so they don’t even have time to put their shoes back on.’ I remember finding out that one of my classmates was a LITERAL Baron, and laughing because he’d seen my tits on a photoshoot in 2nd year. I remember being in the smoking section of a club, and a lad came up to me saying ‘you were in that Pharrell Williams video!!’ I thought it was a shit chat-up line, but he pulled it up on his phone, and there I was, walking across Granary Square, on my way to go get lunch from Pret. I remember being sat in the studio, watching First Dates on someone’s laptop, when a delegation from North Korea came round on a guided tour. They waved, took pictures of us all hunched around the laptop, and then left. This is god’s honest truth.

I went to Berwick Film Festival a few weekends ago. On the whole, it was unexpectedly chaotic, so I wouldn’t know where to start a review of the festival itself. I just had a lovely time on a mini-break I wasn’t paying for; I went for a run along the beach, went on a boat trip, and thoroughly enjoyed an all-you-can-eat Full English Breakfast buffet. So: 10/10 had a lovely time. The programme itself was good, but out of all the films I saw, Manifesto by Ane Hjort Guttu was the one that stuck with me. Manifesto is a film about an art school that has recently been absorbed into a large national university. It flicks between interviews with staff and students, wide shots of the new university building, and little bits where it follows people around while they narrate problems or ideas to do with the building.

The film opens with a scruffy looking middle aged man in corduroys and a V neck jumper. He stands in a clean concrete corridor, in front of a heavy metal door. He points down at a brick and says, ‘they’re quite essential’. He shuffles the brick over with his foot, to prop the door open. He looks back at the camera, like his point has been demonstrated. ‘It’s so simple, so beautiful’. Two people sit at a desk and show us photos of the old art school building. It was ratty and a bit old, but it had a free open vibe that worked well; a proper art school. One photo has paint splatters across a wall in the background. ‘This is how an art school should look. But if you leave a paint stain like this here in this school, there’ll be such a commotion. It isn’t allowed.’ As the film unfolds, it becomes a bit clearer. When this art school was absorbed into the larger, slicker university, something essential began to disappear. Something else also started to emerge. Their old building had a normal door, with normal keys, and an entrance that wasn’t policed. There was a communal kitchen to cook meals and be together in community. Now there’s a huge and frightening glass entrance, with keycards that can be used to track movement through the building. They now have to buy meals from the cafe, as customers rather than ‘active subjects’ enacting care through cooking. Students speak about the anxiety of feeling like they’re being watched in the studio, it made them start acting like they think an art student should act, rather than actually just being art students. A title flashes up, it reads: ‘we don’t recognise our school.’

I remember walking into the wide open space of CSM’s main building for the first time. It was like being in a big old cathedral, or the slick corporate headquarters of a massive conglomerate. It was 2013, I was 19, and it scared me so much, I nearly cried on the top deck of the bus back home. Everything was chrome, concrete and natural light. The floors were buffered and polished, you couldn’t open the windows because there was a centralised air circulation system. You needed keycards to get into the studios, and your keycard would only open the doors of the studio you were assigned to. I remember they experimented with ~opening up~ keycard access, to foster a more open cross-curricular environment, but they had to shut it down after a few weeks because someone’s laptop got nicked. One time, my friends used their keycards to sneak someone who didn’t go to CSM in through the entrance barriers, and they were stopped by security. Their keycards were confiscated for the day, and they were told that if they tried that again, they’d be banned from the building permanently.

I went to art school in 2013, and I was one of the first years to pay £9k a year for the privilege of higher education. 2013 was a weird and sticky time. Things felt transitional; we were halfway in under the coalition government, we knew things would get bad, but we didn’t know the extent of what was to come. CSM was an art school in the stomach of a huge bureaucratic beast, and even though my little certificate says UNIVERSITY in big letters, the bones of a radical art school were still in the process of being dissolved in all that bile and acid. We were being taught by tutors who didn’t quite believe in the professional development modules they were being made to deliver to us. We were made aware that we were in an Arts University, rather than an art school, and we quickly realised the gulf of difference between those two things. We saw little exceptions peek through, in ways I don’t think would be possible anymore. Now the gulf of difference has widened, or maybe it’s harder to convey the existence of a difference in the first place. I think the exceptions have disappeared too, or it’s become harder to interject with them.

That same year, in 2013, the Undercommons by Fred Moten and Stefano Harney was published. I can’t lie, I still haven’t read it, even though I know I probably should. I think the gist of it is: neoliberalism is obviously a headfuck, but specifically, universities have become corporate and professional entities. This means universities are structured and funded to serve the interests of Capital and the state. Moten and Harney denounce this professionalisation of knowledge, and define the basis for ~new oppositional solidarities~ that ~defy easy categorisation~. The Undercommons describes a space away from that Capitalist Pipeline, inhabited by people who have been denied resources, excluded, fugitive. Moten & Harney use the term ~maroon communities~. The Undercommons feels parallel or related to Spivak’s subaltern, and I think it’s interesting that academia has so many different terms for the different kinds of people that are purposefully kept outside of systems. This fugitive space feels exciting and live, because it contains everything that doesn’t fit neatly into the institution’s bureaucratic structure. So all these split ends, these odd shapes and hangnails just filter across into an underbelly. I don’t know what comes next. I don’t know what happens once that underbelly is inhabited. I don’t know what the new oppositional solidarity, according to Moten & Harney, looks like in practice.

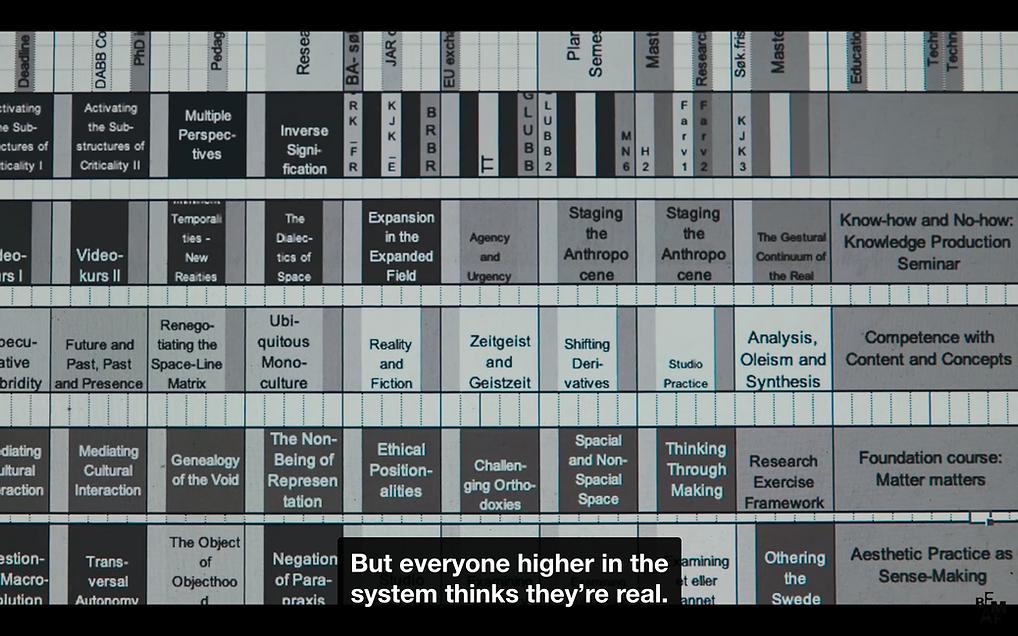

Back to the film. Frustrated by the imposition of this new bureaucratic and professionalised structure, the old art school goes underground within the national university. If they take away the communal kitchen, the art school builds a contained mobile kitchen unit, disguised as a temporary studio wall. It’s complete with worktops, hot plate stove and running water. The camera watches on as they unfold the kitchen, demonstrate how the pipe system for the sink works, and show us the fixtures that keep everything secure and hidden. They fold it out, and back in. Now it’s just a gallery wall again. If the closed air circulation system means windows can’t be opened, they make copies of window keys for everyone, and disguise them as USB sticks. There are fake courses for the digital system, and real courses on a secret booking system. The real courses are disguised as an artwork, and it hangs in the programme co-ordinator’s office, just behind their desk. The fake courses don’t actually exist, ‘but everyone higher in the system thinks they’re real’. The fake courses have names thick with artspeak, descending away from clarity; The Non-Being of Representation, Challenging the Bio-political, Othering the Swede, Znorking the Znork. Another administrator casually reveals that the names were made using an online artspeak generator, which made me snort out loud in the cinema. He smirks, but it’s serious. The university requires courses be taught by practitioners with an MA, but the art school can give you credits from a course called ‘Disgusting Mixtures’ taught by 3 students. Most importantly, the art school elect their own management. There’s a fake Dean of Students (a Pseudo-Dean-on-Paper), who goes to some meetings and sends bullshit reports to keep up appearances. But the real elected Rector is the building’s cleaner. She maintains an overview and keeps things running, while the admin is just sorted out at arm’s length. The bureaucracy that is meant to be so central to everyday operations within this corporate university, is just shifted off to the side. They get on with things, away from the prying eyes of ‘the system’.

Moten & Harney describe the conversion of students and staff, from insurgents into state agents. The university is a kind of pipeline for transformation; it takes unstable quantities, and makes them solid and bankable. In the 3 years I was there, I realised St Martins (the art school) was dead. The place I thought I was going, where MIA and McQueen went, that place didn’t physically exist anymore. It only existed in the memory of some of our tutors, who would at times be complicit in our conspiracies and rebellions. They would say, ‘remember that you’re in an institution…’ Cryptic crossword clue, they’d melt back into the fog they emerged from. Eventually it clicked. We were in an institution, but we were also being trained up in how to fight back. Nothing as material or significant as the interventions in Manifesto, but in small ways. Me and my friends robbed our tuition fees worth in library books. We befriended print technicians and bar staff who’d let us use their staff discounts. We gossiped with our tutors. Best of all, we started writing about exhibitions in our fightback voices, and people started to listen to us.

My problem with theory is that I always want an example, something to demonstrate it all in practice. While I don’t know what Fred Moten & Stefano Harney intend ~new oppositional solidarity~ to be, I know what Ane Hjort Guttu thinks it could look like. Manifesto isn’t real. As uncanny as it all looks, it’s not a documentary, it’s fiction. But in that fiction, it breaks through to the other side of something that could exist. It doesn’t pine after the old, dead art school, or fall back on romance or nostalgia. Instead, it presents us with a vision of a para-institution, running alongside and underneath. To the structure that asks for its compliance and complicit participation, it responds with disguise, sleight of hand. It is funny, because ultimately this is an art school, not a spy thriller. These people are tutors and administrators, not moles or actual literal insurgents. But I think that’s the fun of fiction. It has the ability to expand and stretch out, present us with something new in extremity.

A title flashes up, it reads: ‘we have to organise’.

Imagine this model of a para-institution. Everyone in the main institution, who is required to act in compliance with those interests of Capital and State, is secretly acting against those exact interests. They play pretend bureaucracy, pretend to be state agents, but really they’re all double agents acting to undermine the system from the inside. Now apply it across another institution, one that isn’t an art school. Maybe instead of a huge national university, it is a huge national museum. I don’t normally believe in one person’s ability to change things from the inside, but maybe it’s a collective effort. Maybe all the curators, administrators, registrars etc, they’re all in cahoots with the artists and front of house staff to make sure they’re able to have a good time, get paid well, do good work and have job stability. Imagine if we all just played fast and loose with the admin and bullshit, if we all decided to game the fucking system. It wouldn’t be cheating then, if we all did it. If we were organised, it would just be the way things are.

I know I always whip this quote out, badly paraphrase it, but it’s just the best wording of something so complex and unwieldy. In Morgan Quaintance’s essay, <Teleology & the Turner Prize>, he locates the specific and loaded value of arts education: a rigorous conceptual training, where critical ability is developed through discussion, group critique, lecture and written assessment. It produces ‘critically engaged actors’, who are aware of the governmental, financial and ideological forces that move to co-opt their output. They produce art that problematises and draws critical attention to its modes of display and exchange, as well as the culture, society and politics that made that display and exchange possible. I keep whipping that quote out because it’s a comprehensive way of saying; it can get meta, complicated, sticky - but art schools produce people who know how to handle that complexity, and how to make that complexity something potentially dangerous for the interests of Capital and the State.

I think anyone that went to an art school would agree that those were the 3 weirdest fucking years of their life. We are all bound by the experience, an insider logic that’s defined by being part of a structure that repels you while demanding your participation (and also requires your dissent). It makes me laugh, because I know how this sounds, but I think art school radicalised me. It only works if it changes you, and I think that I was changed for the better. I went into a chaotic void, and in Moten & Harney’s words, I plopped out the other end of it a fully equipped insurgent. The film ends with a vision of this para-institutional art school in full swing. When the sun goes down, the students and staff wheel out the mobile kitchen, and gather to make a meal together. They stand about, laughing and chatting and singing and being together in community. Capitalism loves alienation, it loves individuals as single units, but this is a vision of a social body made up of so many moving parts, all relating to each other, caring and intertwined. Manifesto is a good name for this film, because theory is all well and good, but I want examples. A para-institutional model that demonstrates a practical example for new oppositional solidarities in action - it’s a mouthful, but now at least I know what it looks like.