Mark Leckey @ Tate Britain

GDLP

Emoji summary: 🧙🏻♂️🛣🧚♀️

I’ve been having so many arty conversations with different people in different countries over the past 3 weeks that everything is overlapping, like my brain is now made of damp corrugated cardboard; days are hazy, and my thoughts can’t sit still. but I went to see the new Mark Leckey exhibition at Tate Britain and I’m at my laptop the same day because I want to write about the experience of it while the body’s still warm. i guess there’s definitely this slowness in my fingers from exhaustion that i thought I should mention; a sort of brain fog which, tbh, might make for good, loose writing - one-drink-in conversation, weird and vast.

bc I’ve seen a lot of Leckey’s work over the years in lots of different scales across the UK, and i have worked with him too, so i’m writing this text through a layer of familiarity which, more than anything, feels useful. i say useful because I’ve written about his art before but I think I have a better footing from which to write about it now, having lived a little bit more and spent more time with the mood his work gives off. it’s good exercise as a critic to circle back to the same artists and think about what their work means to you now; and it’s funny bc i say i am a mark leckey fan but up until this point, his art has always presented a nostalgia that really isn’t mine to remember. whether it’s the clips in his films of Merseyside, the inside of night clubs in the 80s, house parties, moon landings, and the older real-er fashion of that time - that’s all distant to me, something i’ve learnt to recognise from cinema and music videos. I wasn’t there. I was born later when the whole world was in HD and liverpool was slightly less of a shithole. but even tho my mum might feel closer to the content, i’ve still appreciated his films and reached towards them because they have style and I enjoyed being in their company. It’s cool art, isn’t it. Loud sirens and people off their faces is entertaining, and then it’s cut with pink skies, concrete, metaphors and road signs I recognise. it all has edge and focus, and i feel matched to it, if not from a different time. I think as well, Leckey’s work has felt good to me because so much other film work by artists is noticeably bad - i am convinced people make it because they hate me personally and want to see me cringe. u know the stuff: production quality’s always way better than the actual content, cheesy script, OTT drama student acting and clunky structure when it’s original / and then art that’s too obvious when it’s a tetris of found footage. So i’ve liked his work yes because I’ve trusted it, but with this new exhibition at Tate Britain, I now feel in on it. like the door’s been knocked open slightly for my generation, like his own sightline has caught up with today. now, I’m no longer the girl wearing an oversized Nirvana t-shirt and saying I love Mark Leckey’s work but now I know all the words to the new album (that is, if Nirvana still existed for this analogy to even land).

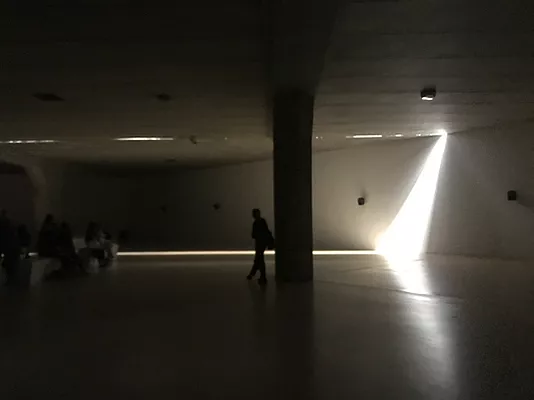

If you haven’t been yet in the whole 6 days the show has been open to the public, you are far away, or this exhibition costs tickets so u aint gonna go, I will describe what it is and what happens inside the show because it is - well, it happens. it is and it happens. it’s between exhibition and event. Sorry, i know descriptions can be the most boring parts of art reviews but i think I need to paint the whole picture so what I go onto say makes sense. It’s one big wide room in which the artist has built a massive motorway underpass (the structure, not the road below it). the ceiling has been lowered, one corner of the room is a rising slope, and there are three blocky columns holding it up in this weird fake concrete finish, as tho the whole thing is a giant architectural model that knows it isn’t what it’s supposed to be but that it’s close enough. There are two long benches in the same look at angles; the walls are white and lights are low. On the longest wall there are two projections showing the same thing far apart; adjacent wall has 5 TV screens hung portrait with wires coming out the top and disappearing into the ceiling; and on the next wall there is a square of posters pasted to it. the content of the projections and TV screens changes but obv posters don’t. they are what look like gig posters but are actually illustrating three different artworks by Leckey. those are ‘Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore,’ ‘Dream English Kid’ and ‘Under Under In’ - the latter is the title of the new work in this room. And then the happening begins.

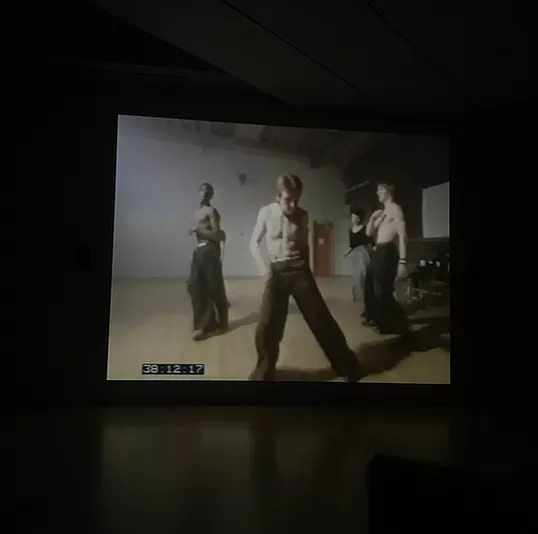

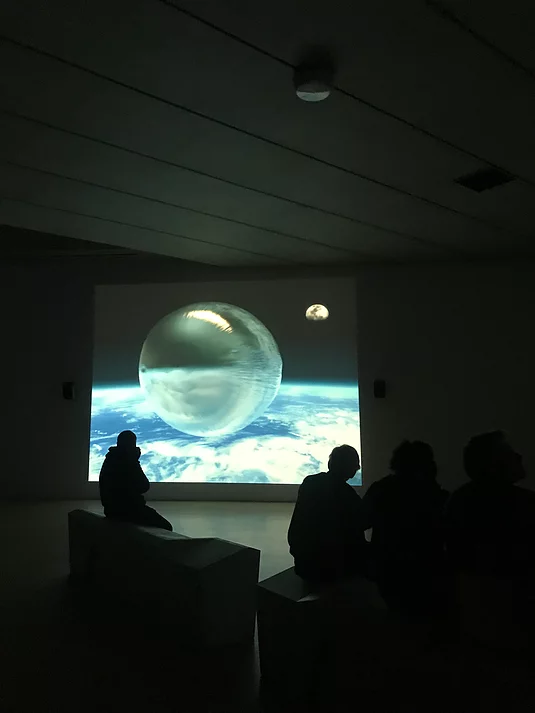

It might be helpful to describe it in acts, because it was kind of like different parts of the room took turns being the centre of attention. I know it’s all controlled by computers but it felt like Leckey was running round on top of the underpass ceiling to puppeteer the show. it lasts a whole hour. in Act 1, the double projection plays Leckey’s maybe best known work ‘Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore’ which is a 15 minute film from 1999 that takes the viewer through found footage of the 70s to 90s of people in dance halls moving in a way I can’t imagine today. they’re gurning, spinning, and their legs bend in bouncy, weird ways. between the bouncing, the film pauses on a few different faces so briefly but it makes them seem unreal. Act 2, ‘Dream English Kid 1964-199AD’ plays on the same projectors. This film is more recent, from 2015, and it lasts 23 mins. it’s wider in its reach; has a faster energy than the dreamy dancing sequences. it starts with a rocket countdown and silver things floating in space, takes us to Liverpool, electricity moving through the air, shadows, drawings, kids legging it, back to the club, and ends with solar eclipses. This is also where the recurring motif of the overpass comes in: both found footage and 3D visualisations with grainy filters. Why is it there?? why are we shown the underpass and motorway again and again? the video feels more personal, assuming the motif has come from his own life (which it has because I slipped and read the press release, it’s from the M53 where he used to hang out with mates / near where he grew up; and that’s what is re-built in Tate Britain today).

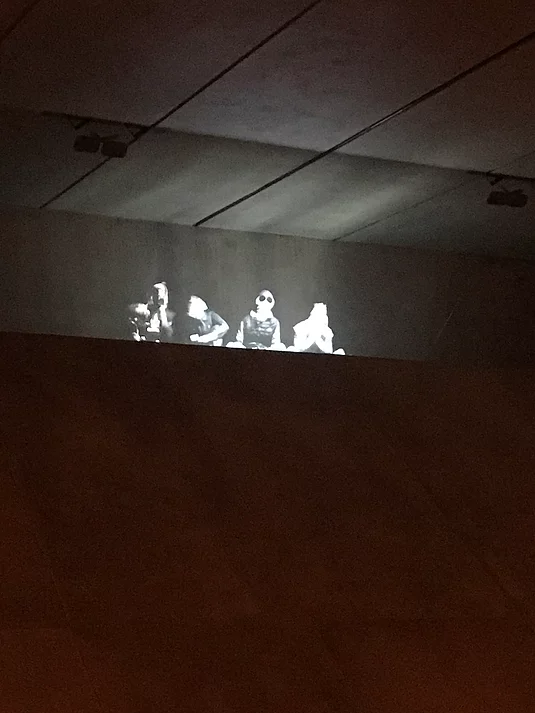

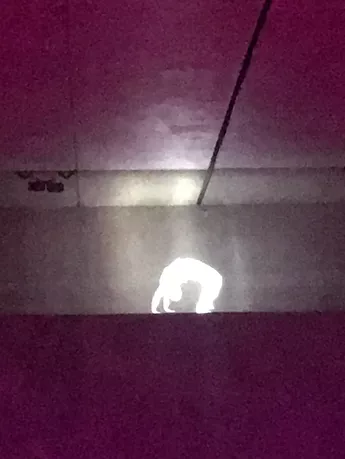

When this film ends, the tungsten yellow lights on the ceiling of the underpass wake up, and the room looks dim and rusty. i was sat on the benches wondering what was going on when a few minutes of music started playing far away, v muffled singing coming from the corner of the room where the top of the slope stops. heads turned and on my second watch through this whole event, i tried to get as close to the sound as i could to figure out what it was, but it was like trying to make out a conversation from the house next door. it sounded a bit… like a hymn in parts, clunky piano and chorus. I don’t know. not like u could shazam it. a few calm minutes of cloudy sound and intermission until Act 3 began, which is a mouthful to describe here now. A projection (or hologram? who knows at this point, i felt out of it but importantly I <wanted> it to be a hologram, for the vibe) appears at the top of the underpass slope of 4 lads in black and white, or infrared greys, hunched over and chatting, scouse and manny accents ringing out into Tate air. The way they speak is broken, overlapping and looping. It’s me me me back again, Ay la, what’s up, I wanna gerroff and leave this place I just want off. where. anywhere? London. Wouldn’t youse? Stuck stuck stuck think youre better than us. Ah listen. Bit mad. Take me out of this world. At this point as a viewer you’ve turned your backs away from where the projections are to watch the hologram boys. A woman’s voice in a london-blank accent says to the one wanting to leave to, ‘come up with me, come up in the world’ and he goes with her, he disappears. the sequencing is messy in my head but I think this is the point when a long white light cuts the entire room, through a split in the underpass I hadn’t noticed until this point, and it falls onto him - like he is the chosen one, holy and ascending. the other lads are wondering where tf he went. Give it all that. It was like av add enough of yous. In a bit laaaa. Woah. Now, the 5 portrait TV screens on the wall on the left show quick clips of actual lads, not just spooky projections, and they look so new and colourful after all the crinkly projections and previous found footage moving image works; they’re wearing adidas balaclavas and that reflective grey clothing that looks like a mirror or a cold sun when you flash a light on it. The lad who disappeared reappears and one of them is like Urgh his face has gone all wrinkly like an old man. Floated up. You trusted him? They’re quizzing him on what happened like, Them. Who. Them. Them that’s in the hill. The bridge. Whispering around us. Ah ees away with the fairies. Sometimes I think he can hear us. Can hear him listening. Sounds hollow. But it smells like something died down here. Across those 5 TV screens, the world goes down to a molecular level in grainy visualisations into shapes that look like caves, and that woman’s london voice is whispering TRESPASSER over and over. it feels like commotion is building, pace is picking up. suddenly the screens are showing flashing blue lights, the police are here (but they’re not here, just the blue and sirens) and they all start legging it. What do we do what do we do???? Stick together and then, and i mean, i didn’t get it at first either, they all start doing the crab. The crab. You know when you have your back to the ground and are raised up just standing with your hands and feet, back super arched and if you’re extra good at it you can walk? They are all doing the crab, on the videos and in a massive silhouette projection where the original two films played in the space. We see them hold the pose strong and deliberate, it’s all very serious, while the sound and energy in the room is waxing. All the noise stops, the crab is the climax, and the lads are happy and safe from whatever it was coming to get them - the police or the spirits or that woman whispering. it ends, everyone breathes out, and the whole thing starts again a minute or two later with Fiorucci back on the walls, from the top.

Whhewwwwf. I turned to Zarina and asked why they were all doing the crab and she said, ‘don’t you get it? They’re being the underpass.’ Well thank god she was there to appreciate what my dead head couldn’t - but that ending (and Zarina’s reveal) sealed the deal for me. I really enjoyed the experience. Partly, i got solid viewer satisfaction from being taken through a 1999 film to a 2015 film and finally a huge 2019 pay off. it was cool to see the chronological processes of how a single artist’s thoughts develop all laid out before me and not have that be in the boring and typical style of the retrospective that is often an end or a funeral. this feels like a retrospective that makes way for the future, and whatever Leckey goes onto make next. Partly, i loved the form and being wrapped up by a story in this theatrical rehearsed set-up: all tech, angles, and there being double projections of the same thing meant your periphery was always flashing, so full in the room and stimulating. But most of all, beyond form, the value i got here and the reason it had energy for me was the story. the content and language brought to mind this joining up of class, magic and music that i don’t often see together. I mean, I guess you could count certain moments of the Peaky Blinders storyline and soundtrack. but maybe Yank Scally is a better example - class, magic and music come true. Yank Scally is a musician from Liverpool who brought out an album earlier this year called ‘There’s Not Enough Hours in the Day.’ we had a chat once and i think we are the same age. The album cover is a vector illustration of a wizard at a piano before a starry sky, ciggies and a funny smiling candle. He’s a recording artist but in photoshoots in character he can be seen wearing a red cloak with white trim and a face painted white with thick black symbols that look cultish or something to ward off evil. There are a lot of collaborators on the album, and lyrics range from ‘I’m a nobhead depending on who you spoke to,’ ‘magic spells, can we be friends,’ ‘bulletproof wizard, go where the road takes ya,’ ‘aint enough hours in the day, aint enough stars in space,’ and there’s even a prank call to an american record shop at one point. All music is emotional but his swings from moody resignation to high fantasy, with piano, violin, and importantly, scouse accents rapping and singing, taking the stage in a way I’ve never heard them before.

With this Tate Britain show, I think Leckey is in the same field as Yank Scally. I feel like they’d get on together sitting in this messy electric fairytale landscape, and anyway they’re coming from the same place, literally. In my big opinion, what they are doing by instrumentalising the aesthetic of magic in their art and music, is making themselves and the working class feel less powerless. We do the crab as a protective stance and we are saved; we dress in red cloaks, paint our faces and become superheroes. When the fairies try to kidnap us, when the police come to get us, we can use magic words, poses and shield ourselves with reflective mirror clothes to escape their gaze; inhabit bulletproof wizard characters to feel better again, float away from reality, struggle, and go where the road takes ya. I can’t quite untangle the exhibition or the album away from one another because they both feel like whole spells. What i read in it, probably because I need this reading, is Leckey’s exhibition as a record of crossing class lines - all the confusion and fallout that must come from his own world beginning at the side of the motorway and leading down here to London, the art world, and now centre stage at Tate. what would have happened if he’d never left the north? do artists nowadays still need to leave Merseyside to actually have a career? and if you do leave, if you’re sucked up by the capital, do you need to make art like talismans to keep yourself safe? are you ever really the same? is it bad to change? and does anyone wish they could go back to the side of the road? i love talking about this stuff because it matters to me, and yep, i thought this show was boss. i’m glad for the feelings and glad the artist is looking back, and it’s all done so well, chef’s kiss. I couldn’t give two shits about the london reviews they feel irrelevant and I am not gonna read their boring writing, so i hope with all my heart Tate pay for northern critics and artists and lads and my mum to come and see what he’s crafted; i for 1 would love to know what everyone else who matters thinks about it and if they felt the same magic coming through.

You can find Yank Scally here