Payal Kapadia @ Berwick Film & Media Arts Festival 2020

ZM

Emoji summary: ☁️ 🌄 🕟

I want to spend some time away; I’m embarrassed by how eager I am for our December break. I think I have had enough of this year, I think I’ve seen enough art and I have thought through enough. I’m old enough to know myself, know my body, and when it is full. I am full now, n I would like it to wrap up and finish already. So I feel like any artwork I turn to this week will have a tough time with me; I am not an eager or generous audience. I spent some time with the Berwick Film Festival program, because Gab signed me up for press access, and it was all nearly coming to a complete close. There was a lot, a lot, it’s a bargain of an offer tbh; like scrolling through netflix, but it was all actually good and obscure and clever and beautiful. I settled on the trilogy of short films from Payal Kapadia: <Afternoon Clouds>, <The Last Mango Before the Monsoon>, and <And What is the Summer Saying>. In my Friday 4.30pm feeling, I’m gona keep this cute n just relate to you how I thought and felt through the films as they ran on before me. No heavy thoughts, no shaking out higher meaning; first glances only.

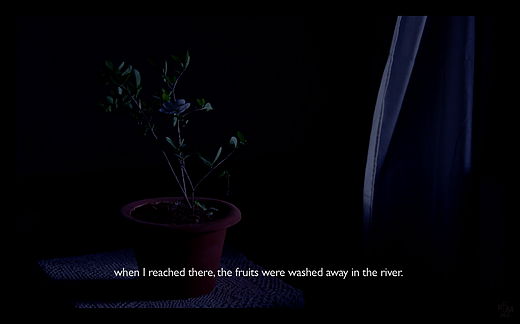

Afternoon Clouds is set in an apartment, an elderly widow and her maid while away an afternoon in quiet tedium. There are these flat shots, with background harsh up and perfectly set against the camera, that make those moments feel like a stage or a postcard. A lot of this film feels like a postcard tbh - the way that language is punctuated by heavy absence and interruption, clipped and brief. The scenes are cut with illustrated cards; little paintings by Arpita Singh. They have a loaded symbolism that I can’t quite read in relation to the rest of the film. Halfway through, Malti (the maid) is visited by her lover. We don’t know if this is a dream or real life, and they hold a silence between them that could be intimacy or sadness. He’s been away working on a ship, and she’s been stuck in this domestic role; it builds a sad silence that swells between them until they are interrupted by the pouring smoke of a fumigator. The widow, Kati, dreams of her dead husband; she tells Malti about it as they’re cooking dinner. She dreamt that clouds rolled into the house and carried her husbands voice with them; he called her to come and collect fruit from the trees. As she followed, she found the fruit was already washed away by a river. The fruit came and went around her, rolled over and passed her by completely. There’s a tense stillness to the dynamic between Kati & Malti, a widow and her maid; even if it’s only fiction, my heart hurt a bit for them. Alone in their apartment as the clouds, lovers and fruit passed them by. At the beginning of the film, Kati & Malti stand looking at a flower in a pot; it’s in bloom, but will only bloom for 2 days before it dies away. Malti asks, ‘why don’t you grow a flower that blossoms through the year?’ The widow never answers.

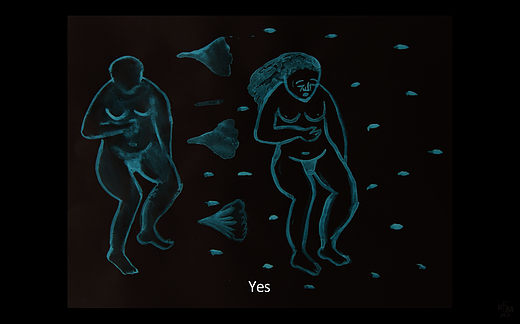

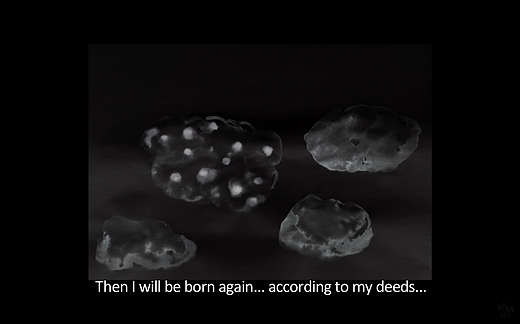

The Last Mango Before the Monsoon is like a slippery patch on the floor. The Berwick program description underneath it opens by saying, it ‘has no central character, narrative arc or clear progression. Its scenes are non-linear and flow freely into one another’. It opens still and sticky warm; an old woman sits and eats a mango in the hot dark, the light in a far room shifts behind her. Rangers wander through a forest, installing cameras to monitor the movements of elephants, they hope they can use this to track them, so the elephants don’t come into contact with humans. It cuts to the greyscale monitor footage; there’s a solidity to the isolation of that, as perimeter and distance. This heavy solid slips into grief; a ghost speaks, ‘I was wandering for a long time in the forest. But I failed to become a part of it in this form’. This speech is narration over watery drawings, villages and trees. The grief and loss voiced here is gristly and tough in comparison to Afternoon Clouds. It feels like the sinewy fat on a piece of meat; like it should be ~doing~ something, connecting or moving some other body, like it should be vital; but it just melts as you swallow it, so it was only small anyway. Chewy and soft, never quite spoke aloud, or summoned into full being. It all slips past, a moment away from itself, like dream or memory. The film takes place using (or only following) gesture; the illustrated moments reappear, but I get the feeling that this is a way of making a film that dissolves into the image and sound of itself. Non-linear cloudy scenes, cloudy progression, everything slips and slides into each other and falls away, apart. Voices call from nowhere in particular, never attributable to a body; the film forgets bodies tbh, forgets their presence and refocuses. Back to the slow forest, leaves stirring and mist rolling off the hilltops in thick curls.

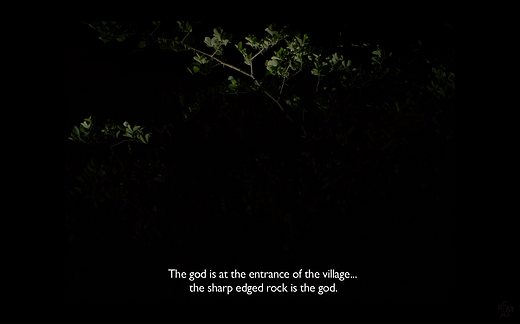

And What is the Summer Saying is the furthest and loosest one, set in a village and depicting life there from a separate distance. Torchlight shifts over the leaves and branches of a great bush; slow and sticky again, the narrative restlessly shifts into lyrical image. Bodies are described by the way they rustle the leaves of the forest around them as they move through, like wind or like ghosts. Voices call to each other, but they are shown from afar, from the landscape they sit within. It’s a distance, and a meaningful distance. The characters are all villagers; human, cow, donkey bees. The bees get a slightly special treatment; narrative cards appear and wind out a story of someone who’s intimate and close to them. ‘His father had taught him all about the bees / In the summer months / he collected honey by searching deep inside the forest / I thought of him, with his eyes fixed to the sky / If he stood silently, / he could hear them in the forest’. The bees are quite lovingly, achingly described through a kind of romantic fiction; ‘He told me / Bees always travel alone / Once mated, the male bee will die. / That is its only purpose. / As he grows older,/ he says, / He has begun to think more / of those bees / who must die when in love’. The illustrated cards reappear, but now they have a more mystical, magical role alongside this aching bee romance; surreal, in a parallel and shared village of their own. It feels like it’s working on the scale of the sublime; nature towers around us, we are shrunk before its imposing majesty; but then when you get used to that pace, it zooms itself down to the level of an individual human, lying half-asleep on a bed, or speculating about lunch. Smoke rolls off a landscape again; blurry dream folds into the narrative, quietly this time, like a whisper. A cow sits in the dark of a bush, nestled into its cover at twilight.

I am so glad for Makers; God! I appreciate Makers. This set of films has a poetic subtlety that I needed in my dismissive haste. It forced me to read it with care, because there was no other way to view it. I am glad for its watery slowness, the way it pressed against the scale of itself. I am glad that Payal is a Maker, an Artist with the insistence and skill to make something that is so finely and precisely crafted, but without the pretension or preciousness to insist on it being perfectly clear. The program describes it as being ‘between minor, ephemeral feminine gestures’, and I think that sounds like a round and wholly complete description. Minor ephemeral lyric - that is a happy shape in my mouth - like full fat milk, when it coats the lining of your throat.

Berwick Film & Media Arts Festival took place online this year, and it was on from Thursday 17 September to Sunday 11 October 2020. For some reason my press access logins still worked, but i should've written this much earlier so you'd have a chance to catch it in time - apologies for that!