Sutapa Biswas @ Kettle's Yard

Emoji summary: 👅🎵↪️

This week’s review is going to be a bit of a different stretch for me. Gab says she writes with the audio in mind, so that her voice is the first and best way to experience her texts. I don’t really ever think about the audio until it comes to uploading. I always imagine my readers in bed on a Sunday morning, or on the top deck of the bus. But for this text I want you to listen. Close your eyes. I want you to imagine this exhibition while I walk you round, and you can conjure up the image in your mind’s eye, like an extended art guided meditation. OR, if you’re in Cambridge between now and 30th January, maybe you’ll go into Kettle’s Yard, and we can make our way round the gallery together. Wouldn’t that be nice! Either way, either format, let’s be friends. Let’s go on a lil art date. Maybe we’ll hold hands and get a drink after, and you can say ‘let’s do this again sometime’, and I’ll say ‘yes, that’d be so nice’. And I’ll mean it.

If you’re in bed, on the bus, or in the foyer of Kettle’s Yard, close your eyes and be still for a moment. I need to give you some info. This week’s text is a review of Sutapa Biswas’ show: Lumen, at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge. This show is one half, the other half is at BALTIC in Gateshead. That show at BALTIC is more moving image heavy, more contemporary. This Kettle’s Yard show has a more retrospective focus. I don’t know about you, but I find reviewing retrospectives so hard. There’s almost no point in doing it, unless the gallery has fucked up, or you’re discovering the artist for the first time and you want to impart the good news. It can feel like there’s no place for opinion when you’re cycling through the collected mass of a life’s work. So let’s just do away with opinion and have a nice time.

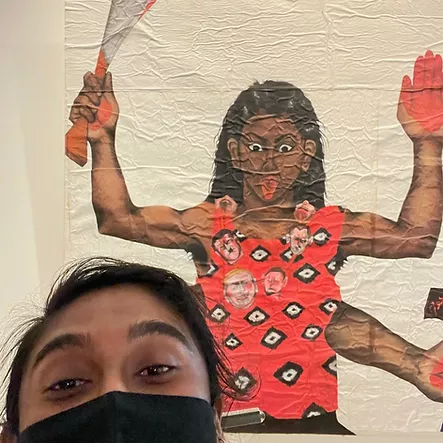

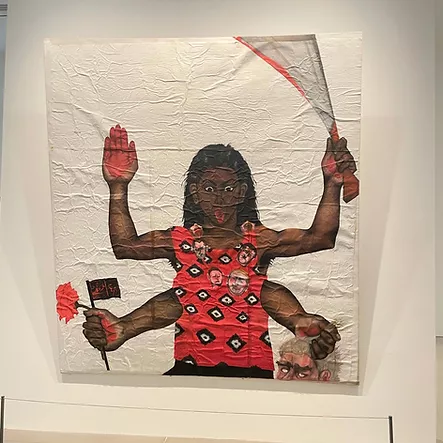

Sutapa Biswas has been an artist for a long time. Her work spans all the way back to the 80s, a heavy history against the backdrop of the Black Arts Movement. Maybe her name rings a bell? For me there is one specific bell: a painting that’s always hung slightly on a tilt, so it towers over you at eye level. If you’re in Kettle’s Yard, open your eyes and head down to the first gallery to go see it. It’s called ‘Housewives with Steak-knives’ and it’s right in front of the door. We’re looking at an image of a dark skinned brown woman in a red sleeveless top. She has four arms: two raised above her head, two drooping towards the bottom of the frame. On the right: one hand is holding a curved sword (the blade’s edge is lined with bright red blood), one is holding the severed head of a white man. His eyes are cloudy and white, lifeless. His eyebrows are knitted together in a thick scowl. On the left: her lower hand is holding a red rose and a flag, the upper hand is raised flat towards us in greeting. All four of her palms are bright red. She has a string of miniature severed heads around her neck like a cool chunky beady necklace. One looks like Hitler, but the others are indistinguishable; they’re just generic white men. Fun fact that I didn’t know until writing this: the flag in her lower left hand is a tiny little reproduction of Judith beheading Holofernes, that famous Renaissance painting by Artemesia Gentileschi. That feels significant, doesn’t it? A painting of a woman committing an act of violence, by one of the few female artists at that far end of European art history.

Anyway, the woman’s face is the part I always remember. Her tongue is bright red, poking out of her mouth like a tapered flag. Her eyes are wide and wild, eyebrows arched. The four arms might be a hint, but it’s the tongue that’s a giveaway: this figure is modelled on the image of Kali, a Hindu goddess. Her tongue is always out, dripping with blood, because she emerged from Shiva to slay a demon. In popular mythology, this demon multiplied every time a drop of his blood was spilled. So Kali pops out with a sword and a noose, as she slices him she drinks his blood to stop it from spilling. She sounds a bit spooky, and she’s sometimes depicted standing with one foot on her husband (Shiva)’s body, wearing a skirt made of severed human arms, which doesn’t help. But put all the iconography aside. I like to think she’s just a metaphor for time, which can get spooky if you think about it - its absence or its fluctuation. Time feels like a marker of civilisation too, this unwieldy thing that the civilised world has tried to tame by categorising and segmenting into neatly measured packages. But really, time is a bodily thing that must be experienced, that is ultimately unknowable. We just travel through it in one direction and its finer workings are completely opaque, we are unable to really truly perceive it. So she is also kind of a metaphor for this fundamental, uncategorisable knowledge; a deep knowledge, the experiential and the corporeal. So back to the woman in the painting: our housewife. It feels significant that she’s modelled in Kali’s image. Kali is a goddess that slays demons, that represents the divine unknowable, dark opacity, time’s absence and inevitability. That white man’s head she’s holding is a heavy demon. He was hard to kill, but she’s defeated him.

I can’t lie, I think I love this painting. It feels like a good joke, a happy ending. But I am sometimes a little cringed out by the roughness of its symbolism. I have this aversion to firmness, I hate when I am led with a heavy hand. If I feel like an artwork is steering me towards something overtly, I feel myself flinch automatically as reflex. Maybe that just says more about me: my sagittarius rising or the position I speak from and how easily I can read the painting, where it leads me and what that triggers. Maybe this is a more tangled image for you? idk, but I wonder where it leads you, and what that triggers in your brain. But for years, this painting has been the extent of what I know about Sutapa Biswas’s practice. The wall text dates this painting 1983-5, when Sutapa was still doing her BA at the University of Leeds. And I just think that’s crazy. That a painting an artist made when they were still in art school has become the most enduring and powerful image of their career, the one that sticks in all the heads and history books. Regardless of how I feel about its rough symbolism, I crack up a bit every time I see it in a gallery, whenever it’s trotted out as a loaded representative for the Asians in the Black Arts Movement. Because I don’t think the housewife in this painting is the art world’s god, I think she is mine. She has mad eyes, yes. But me and her, we share an agenda. Maybe I’m projecting, but I think she and I would get on.

Anyway, we’ve been here a long time. Let’s move on to your right and maybe hurry up a bit. There are two paintings in front of you and I think they’re like a spot the difference. The changes are slight: in both paintings there is an image of two brown women embracing. The woman on the left has her head buried in the woman on the right’s chest. In both, the woman on the right is facing the viewer, with two arms on one side. One is embracing the woman on the left, one is raising a weapon above her head. The faces in the two paintings are different though, one is more angular and worried, the other is rounder and wearing an expression that feels icy and cold. The weapons are different too. In one painting she is holding a gun, and in the other she looks like she’s holding a chunky three-pronged fork - like a trident, but hand held. The thing is, both figures are in both paintings. You can tell from their outfits: the angular worried woman is wearing an orange sari, the round-faced icy woman is wearing the same red top from ‘Housewives with Steak-knives’. They’re just flipped, comforting and defending each other in turn. Apparently the figures are based on Sutapa and her sister. I think you can tell that they’re sisters from the way they’re holding each other, but I don’t know who’s who. If I had to guess, I get that older sister gut feeling that the one in the red top is the older sister.

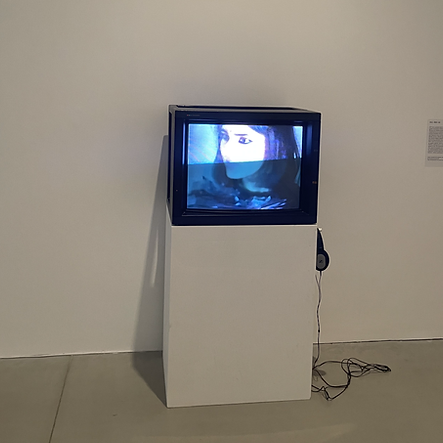

Round to our left now, there’s a lil cube TV with a retro looking film playing. If you’re there in Kettle’s Yard, pause this and put the headphones on. If you’re imagining your way round, I’ll narrate it to you. It’s a film called ‘Kali’, also made when Sutapa was in Leeds on her BA. I think you can tell because it’s got this art school aesthetic quality that I identify with and recognise. The film opens with a scene that feels like a newsreader clocking in with the evening news, a character sits in front of a union jack, reads out a lil primer for what you’re about to see. It also feels like they’re introducing it to you at a film festival or a showcase. I think it’s endearing. Then the scene changes to a dim lit basement. There are 3 characters now: two are wearing tunics made of bin bags, another is sitting on a chair with a white hood over their head. The bin bag figures tussle about, the camera stutters. It’s a handheld cam n it feels retro and homey, janky. Bass rumbles away. It ends with one bin bag figure standing over the other, who is crouched, hunched over on the ground. The standing bin bag figure slowly paints a line in an S shape on the crouching figure’s back, another line in an S shape across. The film stutters over itself and plays that part again. It’s a swastika. The figure is drawing a swastika on the other one’s back in bright red pastel paint, and the final cutaway image is very dramatic. The 80s were a different time, a different country. My Mum remembers being chased down the street by skinheads. And Kali is tongue in cheek, and young - it feels like its got that fresh and new confrontational energy, the kind that is a raw wound.

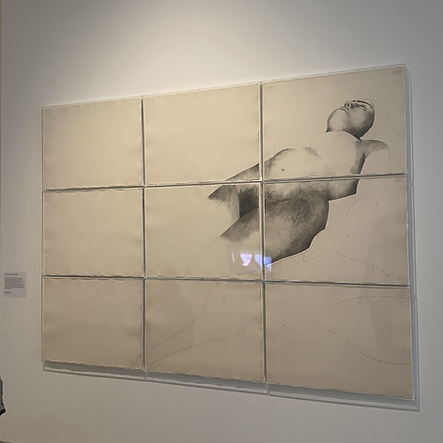

Behind you, opposite the cube screen, there’s a massive line drawing. The image shows a reclining woman, Sutapa’s sister again. The contours and shapes of her body are rendered from this jarring angle, flattening and compressing her. Now she looks like territory, topographical, a body that is also a landscape. The drawing is done in pencil, and parts of her thighs and stomach are shaded in. The rest is very thin pencil and along her outline there’s a long trailing sentence. We should stoop down to read it: ‘to murmur. To mutter. Heart, lungs etc., a rustling sound from the heart. Stream ~n. To run with liquid. To touch stone. To touch stone. Sound.’

Off to the side, there’s a series of three big black and white prints, the colours are inversed and wiped. A woman in a printed sari is holding a wide eyed baby, the kid is wearing a garland of flowers round its head. These three prints are hung in mid-air, hovering in front of a thin, wide print on the wall, showing a little letterboxed view of the lips of a statue. The image of the woman holding the child casts a shadow in its image over the lip print and the wall. To the right of that, there’s four black and white photographs, hung neatly on the wall in a line. They show the bare skin of a body, a stomach, with images projected onto them. A classical Indian sculpture, scaffolding cladding a building, flat rooftops and the rounded dome of a jutting tower, people standing knee deep in a flat body of water (there are trees lining the horizon). In each print, the image across the stomach is being cradled by two hands at the base of the image; like it is a precious unborn baby contained within the stomach’s skin. To the right of that again, there’s a navy blue kimono with embroidery unpicked and hanging loose, a neon sign with the words ‘silver green / against dark navy / swallow me whole / and spit me not out’ in white cursive handwriting. Back round to the right, two black and white photographs of a woman in the dark, curled up and lying across an Indian classical sculpture (it’s either a printed image, or the real thing and I can’t tell).

I don’t know about you, but I felt this surge of energy and excitement when I came into the room, and it has all just slowly dissipated. This is where retrospective feels like a format that knocks the wind out of what we’re seeing. Like, it’s nice but I think this is just a bunch of stuff and I have seen too much too quickly. I wish there was less; Greatest Hits only, with a slimmed down tracklist. I don’t know how to sort through the images I’m seeing and I don’t know how they relate to each other, if at all. I wonder what you think, standing in the room, or imagining it all in your mind’s eye; how does it make you feel? I guess this is just the way a retrospective has to feel, especially for an artist like Sutapa Biswas, who works through wide disciplines - photography, drawing, painting, film, the kimono piece is social practice, the only thing missing from this room is sculpture. Maybe it’s more about the conversation that’s taking place across the works? But I don’t know what that conversation is exactly and I can’t parse it in snippets. Maybe it’s about the body and history, or just culture as a vague amorphous imagined entity. Not ~discourse~ in the conceptual or abstract sense, maybe it’s just about communing with the past. History, like a splinter, under the skin of an image. I think in that case, the paintings speak clearer. The photographs have got a jumbled quality; the symbols and signs of what they’re trying to communicate is too buried beneath this film of slickness and pose. Either that, OR: I think painting renders a more complex understanding of the political sensibility held within the images. I hope that makes sense. Maybe photography needs a more subtle hand and I am tripping up over what I’m being told? Painting gets away with being heavy handed because it is an image conjured at the artist’s behest, it rests at a slightly different register, flattened or stripped back.

Ey - pull your phone out and google ‘SUTAPA BISWAS PAINTING’. There’s a really nice one: ‘Through Rose-Tinted Windows’. It’s made up of six panels, a horse’s upper body in a red landscape against a baby blue sky. I like it a lot, but I don’t quite know why. I think it’s because it feels like such a wide leap from the paintings in the room with us now. I just want to know how we got there. Go back to the entrance of this room and look at ‘Housewives with Steak-knives’, then back down at the horse. They’re so far apart, they don’t really communicate but they also make complete sense next to each other - don’t they? I don’t know why or how it works, but I feel like there’s energy or tissued mass between them.

Now we’re going to make our way to the second room, across the hallway. There’s a film playing, called ‘Lumen”. Maybe you want to watch it uninterrupted. I’ll describe it quickly for those of you listening from afar. A woman in a plain black sari, with her hair slicked down in a middle part. This is our narrator. She walks through a grand house, it has empty rooms and dark varnished floorboards. She is reflected back at us through circular mirrors and appears in doorways. She delivers a monologue that is cutting and barbed. She tells us about a journey, a ghost, a crow. Then a landscape; the sun sets over a paddy field, the sky is navy blue and pink along the horizon. The knotted roots of trees twist around the stone railings of a balcony. This is all intercut with archive footage: grainy shots of a white woman in a white dress walking across a manicured garden, a turbaned man walks across the screen behind her almost out of sight. The severe narrator puts glass marbles into her mouth: one, two, three, her cheeks are bulging. More archive footage, Mughal architecture, columned halls and courtyards, all empty. The script is long and winding, but it tells a story of a journey over the seas, to England and back. The narrator is rude at times, aggressive, confrontational. She questions things rhetorically, for dramatic effect. She speaks loud and slow and angry - good. If Kali is a raw wound, then Lumen is this rage from holding something in for decades. It is a mature anger, a slow burn. It taps into reserves, moves carefully. But I don’t think I like it as much as I like Kali. I still identify with that younger energy, the kind of confrontation that rips with clumsy but powerful hands. I feel a generational gap between myself and Lumen; I don’t see the point in looking back at the journey yet. Lumen zooms out in its focus, across time and country, but I am still stuck in that stage where this country and its limits are pressing in on me and making me unstable. I want to land punches, I want to laugh out loud in the face of something I can spit at. Lumen is more demure than that. It feels austere.

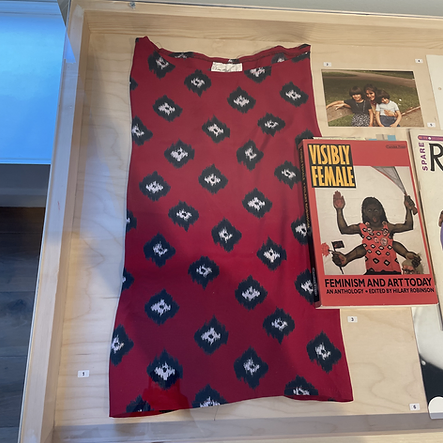

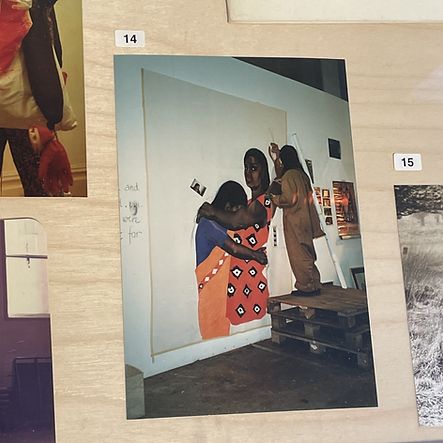

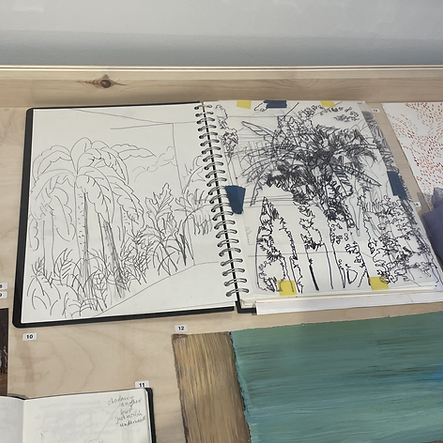

Back out of that room, we’re going to go upstairs to a little reading room or archive kinda set up. There’s a long table with some printouts and publications. But go to the little glass topped tables off to the side. And LOOK! There are loadsa bits n bobs. The ones on the far side of the room are best, because they’ve got the actual red top that the woman in ‘Housewives with Steak-knives’ is based on, the little Miss Selfridge label is showing - that kills me. In and amongst all the publications and gallery handouts there are pictures: of Sutapa painting one of the images of the two women embracing, behind the scenes, family pics. There are little sketchbooks with plans for paintings and observational drawings of landscapes, travellers notebook, scraps of notes. There’s also the script from Lumen, which I want to reach in and grab so I can flip through it. I think I’d have liked it more as a text, don’t you think?

Spend a bit of time with the bits n bobs, and while you do, let’s chat about our thoughts now we’ve been through the show. I think I have a lot to say and not much time to say it. So I’ll say it all quickly.

I think it’s interesting to see this show as part of a wave of retrospectives; artists from the Black Arts Movement are having a resurgence and over the past few years there’s been a move from institutions to recognise their work and practices, bring them into the fold through these retrospectives. It’s interesting because I don’t think its meant to make up for the relative distance they’ve been treated with up until this point. I think it does something else, and if we’re going to ever understand what that is, we could all do with re-reading Rasheed Araeen’s letters. Also, just really think about what that kind of neglect from the art world at large can do to an artistic practice - for better or worse, it has an impact. If you’re still at the glass top tables, go over to the one by the door. There’s a little hand-out from The Thin Black Line, an exhibition at the ICA in 1985, curated by Lubaina Himid. I’m not adverse to looking back at history, I just think I want my interaction with it to be careful and productive. I was shook when I clocked how young the artists included in that show were at the time. Sutapa was fresh out of art school; Sonia Boyce and Maud Sulter were both the same age as her too. Barely in their 20s! Lubaina, Claudette Johnson, Ingrid Pollard, Veronica Ryan - they were all barely 10 years older, in their 30s just about. But I just really want you to deep how young that is in the grand scheme of things still. Just imagine what would need to take place for something on that scale to happen again now? What kinda fate, what would we have to engineer to make that possible? I think I sound a bit jealous when I say that, but I don’t mean it in that way. I just want to think about what’s different now we’re post-Black-Arts-Movement. What dent did all of that make on the institutions of the art world, especially now they’re getting retrospectives and MBEs.

As well as that, I have got such complicated feelings about political Blackness. I’ve been trying to avoid getting into it until now, but I really can’t not mention it when talking about the Black Arts Movement, because that’s its entire premise. Political Blackness uses Black as an umbrella term to refer to people of colour widely, so Asian artists like Sutapa are part of the Black Arts Movement, despite not being understood as Black now. And I say complicated because despite the fact that it’s clearly just an incorrect handling of words that should (and do) have meaning, I have a huge capacity for generosity when it comes to the past. I think I understand the term as a contraction, kinda like BAME, but less external. Like… if you experience racial oppression, white violence, you have common interests and concerns. Identifying yourself with others through similarity, solidarity and what you share is a nice sentiment, and it makes sense in the context of the time, the activism and the groups that were active in the fight back then. But I think you can identify and enact solidarity through other means, that don’t obfuscate the position certain Asian identities have in proximity to whiteness. I don’t think you need to enact solidarity by collapsing a wide range of people, with very different experiences, into the same word. I think that point is really important, but in this show, there’s not really any handling of political Blackness as part of the backdrop Sutapa’s work sits against. And I think that might be a problem with retrospectives as a format: remembering important artists as individuals, rather than as important to the networks they were (and are) a part of. I don’t know if it would be possible to have a conversation about political Blackness in this show, with its singular focus. It would feel shoe-horned in, because the wider context of community is missing until you make it to this archival reading room space.

I don’t know. I guess that all just speaks to a wider need to remember through history, rather than accessing history through individuals and their singular output. And none of that really makes me feel a type of way here. I still enjoyed this show and the time I’ve spent with you. I wonder what you make of all that? Do you feel like I’m reaching with that point about political Blackness feeling like a missing context? What do you think we can infer from the wave of Black Arts Movement retrospectives? Where do you think this show sits against that wave? And I don’t know how to phrase this question, but I’ll have a go: this generation of brown and Black artists had such erratic careers in relation to institutions. What do you think they’re owed? By those institutions, by us as a public, and by me: an idiot baby critic that has had an easy ride, because there were people before me that fought for the path I walk. I’m being flippant, but I think I mean that question sincerely. How do you feel about that all? Tell me the next time you see me, because I’ve gotta go. Get home safe, love you, see you soon!

Sutapa Biswas's show, Lumen is on at Kettle's Yard in Cambridge until 30th January 2022.

This text is a commissioned review, we were paid £200 (+ travel). Kettle's Yard approached us about getting involved with the public program, but we suggested this commissioned text bc i wanted to go have a look and review it anyway. Please check our accounts if you're curious about this or any other jobs we take on!