The Problem with Bad Art & how the game industry could help us

I don’t think we talk about bad art enough -

[When I say ‘bad,’ I mean poor production quality, low power, no presence. When I say ‘art,’ I’m thinking specifically about the art that flows through institutional structures, made by artists that opt into this industry; the full package of public exhibitions, opportunities, funding, touring, careers and… the discourse]

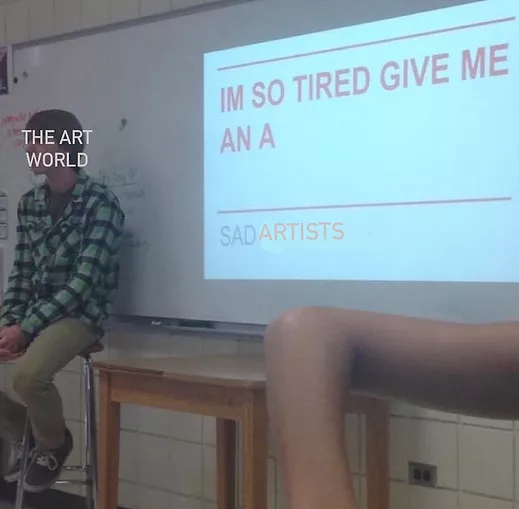

- it’s mad. We’re so well exercised when it comes to all the spicy institutional critique around the stuff - can talk for hours about money, power, abuse and so on - but we really skive when it comes to evaluating the actual material thing that has brought these structures together in the first place. And like, I know why. Art is often made in isolation or shown to a handful of family, friends and yes-men before it goes out into a world that’s broken. Access to finance and visibility is a conspiracy that favours only a few, and with scarce funding and the stressed artists it leads on, people are just happy enough when something finally sees the light of day. They have no steam left for criticism even when the artist has made something that’s… just a bit shit. I sympathise. I understand why our industry’s position is: pretending everything made is good because isn’t it good it’s been made. We are the meme of the student sitting on a desk in front of their class presenting a PowerPoint titled, ‘I’m so tired give me an A.’ And then on top of that, artists, curators and most writers won’t dare offer up any criticism less than neutral - publicly or privately - because they don’t want to risk severing ties with anyone in the very social workspace we find ourselves in. It’s easier for people to just not Instagram a shit exhibition than bother saying, ‘I think this could have been done better.’ For most people, it’s not worth the heat.

The bad art stays up, and artists and institutions stay getting away with it. And I’m not talking about taste and stuff I don’t personally like, I really do mean quality in the most common sense of the word. There’s plenty of art I could have liked if it was a little more ironed out, and stuff I should have liked but it was raggedy. That low quality bad art is my short hand for things like: exhibitions where it looks like they ran out of time and fucks to give. Exhibitions where they put everything in the show without a moment to cull and figure out what they should take back to the studio. Bad art is in iffy compositions, unplanned awkwardness; an unpracticed performance that is lifeless, endless, adds nothing to the world and entertains no one. Crap drawings underneath traditional and digital paintings or embroidery that need better foundations of drawing or all of the work on top has been a waste. Short ideas, wide absences between artwork and audiences; and visitors left wondering why they came all this way to see something that should have been the first draft and not the only draft. Do you get the gist? Like, how many times can we see the same hurt idea in its shoddy little form? I see artists hammer styles together in a way that seems careless, especially when the skill isn’t there to pull all these different styles and forms off: like jarg graffiti that undermines the work of graffiti artists. Artists just want to ‘have a go’ but you still need to try hard, don’t you? I think what if it was bigger, brighter, smaller, clearer, better? It could have been so much more than it is and now it’s too late. The artist never sought out the conversation that could have helped them get there - and that’s the way it almost always goes, because nothing is set up for supportive interventions, crits, a quiet word, some new ideas and encouragement. In the rare crits that take place after university-level, I watch people get hung up on the subject of the artwork, the airspace around it, and everyone congratulates the artist for starting a conversation. But what if it looks a bit slapdash? What if they could have practiced more? Most of the time, the artist doesn’t want to hear it and nothing gets resolved.

At this point in the text, I imagine some readers will be convinced I am evil and I should just let people make what they wanna make, however they wanna make it. Part of me agrees with that sentiment but more of me thinks there’s too much at stake. Bad art in the public eye risks public value and thus even less funding than we have now. Bad art validated by the art world shits on the mental health of artists who care deeply about what they make, have actually honed their skills, and stay honing - organising their own development, mentorship, refinement and growth. I don’t like that those people have to sit on their hands while they watch others with less magic pass them in the queue to a career. And then ultimately, obviously, most importantly, that public I mentioned deserves meaningful experiences with thoughtful art now more than ever. I couldn’t have made it through lockdown without stories, TV, films and games keeping me company in the dark. We all need strong art in our lives, like, we literally need it, so we should care more about trying to make some very good stuff.

But if artists aren’t going to seek out rigorous critical input for themselves, if the curators who work with them aren’t going to say anything at all, and if art critics aren’t going to catch it when it’s even further down the line, what are we supposed to do? Professionally gaslight one another forever? Why can’t we talk frankly about shaping things up? And why is art still fumbling when other industries have things in place to make criticism an embedded step in the process between creation and release? Some people who write books have an Editor - a close one-to-one relationship with somebody who tries to keep their work tight, clear, and ultimately helps to evolve the creator’s vision towards its final form. The worlds of music, fashion, film and TV all benefit from more chefs in the kitchen, with producers, managers, teams and crews to keep the standards high. Artists are just emos playing hide and seek with the mirror. So anyway, the point of all of this rambling, is that I’ve been thinking a lot about the game industry as a source of inspiration because even though it has its own major issues, there are specific roles in place that are dedicated to criticism while things are still in flux. I think I am jealous. I envy the way critique is inherent to game-making before, during and after the work is developed. I want to run back to our art-audience in particular and shout about two roles: Games Testers and Community Managers. To me, both signal something optimistic and open, and even though art-equivalents would work very differently in practice, I think they could do us a lot of good.

Let’s start with the more culturally known Games Tester, whose work sits within Quality Assurance. The Games Tester’s job is to stress test a product to find where the game starts to tear, crash, get buggy. Testers show the developers where these problems occur, developers try improving things, and then the tester follows up to try and recreate that problem again so that everyone has peace of mind that it has now been fixed. The problems might be moments where the game’s integrity falls apart like walls you can work through or items that do strange things. For example, I was playing Death Stranding last week and when I dismounted my bike it floated. So part of the job measures practical bugs like these, but there’s also testing on the playability of the game as well. That might be controls, difficulty levels, the game’s map and directions, and the player’s general reactions too. Is it fun when they want it to be fun? Is it scary enough; how does the combat feel; is there enough for the player to do or to look at when they have to make it from A to B? In bigger game studios, testers play alongside one another in booths and they are often recorded as well which means the developers get to watch people play the thing they’ve made before it’s even been released yet. Isn’t this so efficient? Games are delayed private theatre where directors can’t be in the wings to hear the audience clap or boo, and even then it would be too late to do anything about it. Games Testing is like an ultrasound that takes check and gets ahead. I like it.

It is a fun exercise to map all of this onto the artist and their art and I can dream big here. There are no rules, I can say what I want. So imagine if you could put up your new series of paintings in a private gallery space or big emptied-out studio, and wire it up so that when a varied team of chatty visitors walked in, you could see and hear exactly what they thought of your new work. The faces they pulled, initial comments, brewing words and afterthoughts. Imagine if you could do this twenty times in different places around the country or world with different groups of people covering all sorts of life experiences and proximities to art-chat too. Imagine if alongside this, there were people who would write up more detailed thought-reports about your new paintings; writing about the size, colours, materials, compositions, subjects, memories, references, relevance to them as individuals and relevance to the world at large. Imagine if they could suss out what it was you were trying to achieve by making them in the first place, and measure you against your own attempts. An annotated report with a circle around the bottom right hand corner they thought looked hurried. And then, once you receive all of this data, imagine you had more time to go back to the studio and work into some of them, restart a few completely, and add something new in to complement the series. Get closer to whatever it is was you were aiming for - a feat now enhanced by the expanded generous reception of others. In my fantasy land, you’re doing this with the support of an artist salary or universal basic income. In my fantasy land, there’s no rush, and you can fold this information in before it is ever made public. In real-life-2020-land, a website matchmaker could work. Something that put invested strangers into groups so they could meet and have a crit over video or text-chat. No personal allegiances only an allegiance to a better (art) world. The groups could constantly be shuffled so you heard from a lot of different people. There could be a section of the website for anonymous feedback too so you could roll the dice and get an uninhibited live sense of people’s reactions. An Art Smash or Pass but with other sections for a more detailed, organised, network. A local face-to-face equivalent could work if it was well mediated I think, but only if everyone agreed not to suck up to each other or hold grudges or take the conversation as being anything other than a discussion of the work’s quality and value and not the person’s quality and value instead.

A collision of art and gaming at times, there is a Discord server I learnt about via a thread from @amberbladejones. If you aren’t familiar with Discord, it’s the umbrella for many different chatrooms organised by communities and set up around different subjects and purposes. Amber writes about Gestalt, ‘a background art based discord server with a mix of people from various stages of their art journey spanning across several disciplines, primarily in illustration, games, and animation with a mix of industry professionals and hobbyists.’ There is an #ask-for-critique channel on here that honestly feels special, full of people asking and answering questions on how well the subject matter is understood, the image’s perspective, focal point, texture, suitability of brush sizes, colours, shapes, tones, palettes - everything. Amber tweets that ‘Art is a visual language we are communicating. I feel critique should be visual as well,’ and so some of the work is discussed via annotations which is a directly helpful and pretty dynamic approach to critique that is rare. Between their willingness to share with one another, the annotations, and the organisation and reach, this is a great solution for the problems I’ve outlined in this text and I only wish it were more common. Maybe in quarantine life and especially for artists who are trying to navigate a career outside of educational institutions, Discord is the way to go.

But I mentioned two roles, didn’t I - Games Tester and Community Manager and the second role is something new to me. I didn’t even know it existed until I made a twitter account exclusively to follow game people, and suddenly I was seeing this job title everywhere; partly because that’s where the Community Managers necessarily hang out. I’m pulling a description for the job off ScreenSkills's website because it is more succinct than I could be, so here you go: ‘Community managers are responsible for the community that grows around the game. That means they attend events, write newsletters, organise social media, set up live streams and find the best way of dealing with criticism too. They are the people who know the fans best. They speak on behalf of the fans to the game designers so that the game can be improved. When community managers do their job well, sales of the game increase.’ Games Testers help work as it is being put together, and Community Managers are there for the aftermath when the Games Testers are now the players. Community Managers are the ones running the social media channels so they’re the first port of call for highs, lows and input, feeding notes back to the developers who can choose, if they want, to listen to people’s requests and send out downloadable updates once the criticism has been absorbed into the game. A recent example for reference might be in Mediatonic, the studio behind the viral Fall Guys, who listed patch notes ranging from ‘Improved in-game store purchase dialogue to avoid accidental selections’ to ‘Tweaked round selection algorithm to select a Team game only if the team sizes can be equal.’ The first is practical and the second is something that drove me mad when I played and I’m glad they’ve taken the frustration many of us had on board.

A Community Manager equivalent for art seems most viable to me as somebody attached to galleries, big and small, who can give a face to institutions where there isn’t one. Like a digital visitor book you could have an exchange with - and this doesn’t need to stay digital, the person could be there in the foyer to chat to of a weekend for example. Imagine having frank conversations with someone in a gallery where your criticism didn’t sound like a threat to anybody’s ego, but some points you wanted to put forward with careful thought. You would think curators and the engagement and education departments might cover some of these responsibilities but the framework and their own incompetence means they can always dodge the criticism offered to them. I sent this text to Zarina to read through and on this subject she reminded me institutions aren’t really interested in changing - why would they be? It’s not in their interest at all, and the standard of the art inside might not hold too much weight anyway if the funding’s locked in and evaluations for funders allow obfuscation of art and criticism anyway. Just, in my dream art world, a Community Manager could do the work of collating all the feedback so that something could actually be done with the comments - artists could see through the looking glass.

The biggest takeaway I want to put forth through my inclusion of the Community Manager though is it could be a call for us to have a more flexible relationship with artworks, which are more often than not seen as untouchable conclusions once they reach the exhibition stage, and not as things that could still evolve in the way that games do. Wouldn’t it be good if we could loosen up around artworks and curation too? Imagine if the Community Manager was hearing a lot of noise around layout and the team paused the show to reshuffle? I’m in my fantasy land again, don’t mind me. Imagine if the artist did a take two of their show in another city based off the reception of the first one. Games journey from private team development with Testers to a beta that people can get a feel of (like a pilot TV episode), to release, commentary collated by a Community Manager, and occasional updates afterwards that soothe and adapt. There are whole Remasters as well, and Games re-released on new generation consoles - imagine this but for exhibitions that move up the ladder. It sort of happens but I still don’t think the push for better standards is there. And again, I know Gaming has its issues but the shape of this process seems a lot healthier than the awkward rush the Arts is committed to. No one is demanding we stay like this; we could work together to change it all if we really wanted to. Plus, I bet the public would have a new closeness to the art world if they saw they had some input into what happened within it, even slightly. I bet artists, critics and arts professionals would too. They could know they were visiting an exhibition they had helped shape. I bet it would all be a bit better as well.

Ah, I want what they have! Criticism is a given in gaming in a way this strange British art space avoids. Even here with The White Pube, I’ve written about exhibitions for years and years and heard back maybe a handful of times from artists. Over my lockdown-months of game reviews though, I have almost always gotten a response from the studio the game came out of. Reviews of games I found problems with still get retweeted, which means I feel validated and more encouraged to carry on writing in a space where critic and user reviews are actively received. It’s prolific across podcasting, YouTube, and the livechats alongside announcements streamed online. Gamers are invested and I know some people get intense with that, and angry, but the fact that there are whole legions of fans in constant conversation around this stuff is honestly lovely to see. And I’m not saying that because of the Testers and Community Managers, all Games are therefore good - and that’s good in the sense they are unarguably polished, as opposed to bad by which I mean unambitious and shoddy. I just think this all adds up to a culture where the majority of games are good in a way I can’t quite grant the arts. There isn’t enough push from the inside or outside to make that happen. The push is in some individuals and it’s rare, and those people cannot rely on the institution selecting them like the claw from Toy Story and giving them a career. So it’s hard and those people get lost by the wayside, left applying for other jobs that actually mean they can live. I understand the difficulty of critique as well and respect that it’s something the maker can always take or leave. It might also be that the maker chooses to reject it completely if they do not think the person really wants them to improve or speaks in a way that isn’t very nice. But… the devil on my shoulder thinks it can all be part of the stress test of figuring out what you want to keep as is and what can change or go. I hope execution and the culture around criticism in the arts gets better but until it does, I’m happy to stay over here writing about all the games instead.