Becoming A Disabled Game Critic

Review date:

Content warning: mention of suicide

I don’t know if I am allowed to say this out loud, and I don’t know if what I’m saying will even hold up under the scrutiny of keener eyes and clearer brains than mine. But I think that becoming disabled has made me a better game critic, and I think I might know why.

I say a better critic, not a great or perfect one, because I just mean it relative to what my writing was like last year when I was creating texts from a different body. I only began reviewing games in earnest when the pandemic started. I used to be an art critic but suddenly exhibitions were locked away. Games were there in my bedroom with me, ready. I loved them growing up so I decided to get to know them better after such a long time apart.

The texts I created over 2020 were a little forensic, though. Sometimes they came off naive, and even in the writing process I often felt as though I was grasping. That’s because I was trying my best to catch up on what games even were. Writing about art had been so easy because I used to make art, I knew it intimately. But writing about games felt like coming in through the back door and trying to pretend I had been there the whole time. The texts I ended up making were often less about the games themselves and more about me understanding what a game was in essence. I was holding that study very much outside of myself in the process, I think, and immediately turning both playing and thinking about games into a cold, professional thing.

It was mostly fine because I was having fun doing my learning on games out loud. And it was mostly fine because the first year of the pandemic was so acutely terrifying; learning something new felt normal in a comfortable, banal way. I was playing these games between job-work, life-work, and trying to survive (by which I mean staying safe inside and becoming an astronaut once a week to go to the supermarket). All fine, all fine. I made it through 2020 in one piece, one highly strung piece, newly calling myself a game critic with a tone that showed I didn’t quite believe it yet.

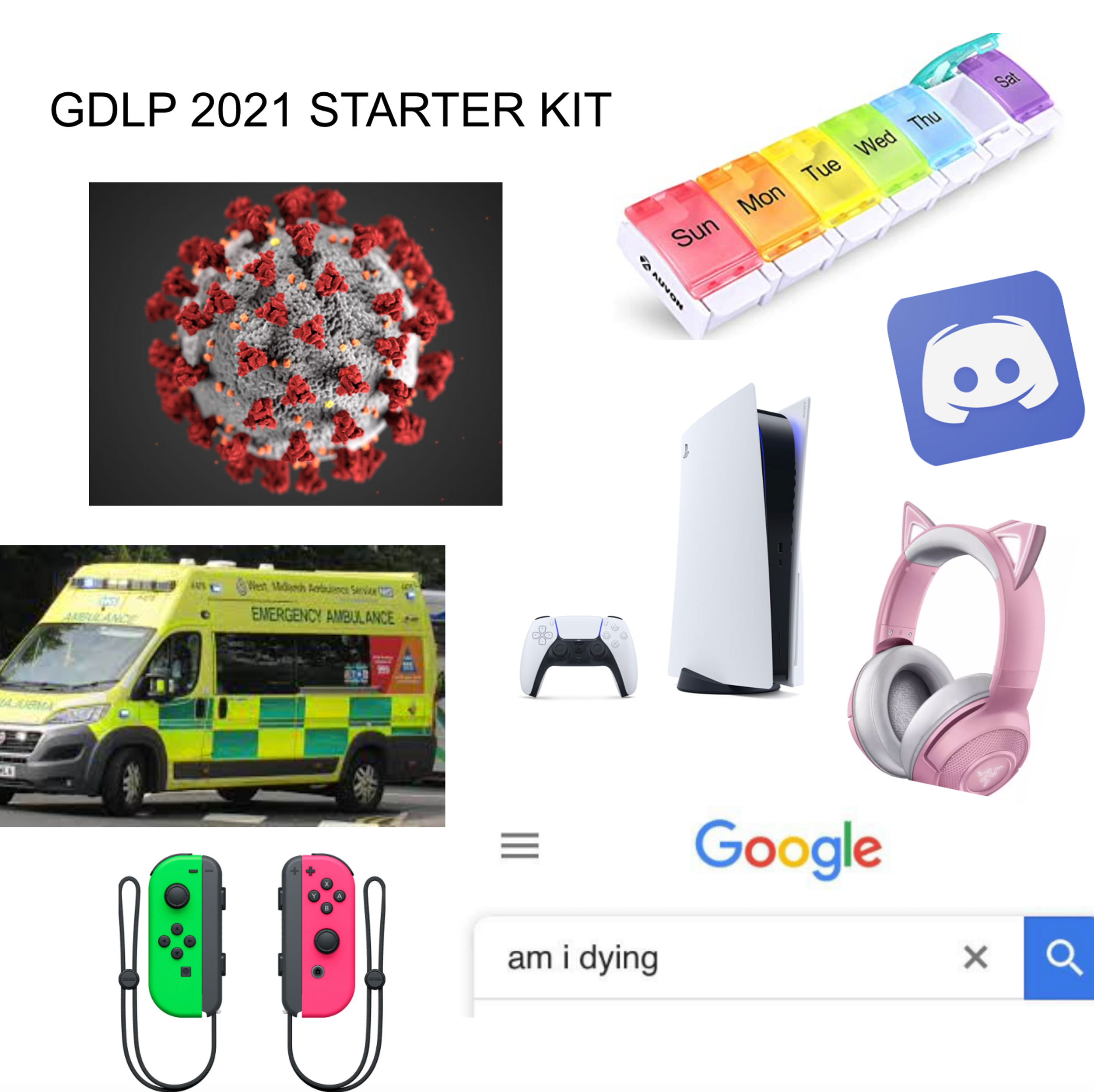

Then, on January 2nd 2021, I realised there was a crack in my astronaut helmet. COVID leaked in. I thought my symptoms were bad but they got worse. The initial COVID infection turned into the post-viral illness final boss, Long Covid. It has been a level with no end in sight. And the damage was done there and then but it would take the following months to see what state it had left me in. I was the aftermath of something bad; a slow-motion landslide, earthquake or storm.

I’m now housebound. Between the fatigue and the muscle pain, my body feels bruised right through to the bone. I can walk the 360 metres around my block very slowly with my stick. If I dare to do that though, life becomes even more impossible for a week. The virus has triggered a Delayed Sleep Phase Disorder that has sent me nocturnal. I also have POTs which means I instantly feel like the world’s been turned upside down whenever my posture changes. It’s all dramatic and excessive. The headline is basically that post-exertional malaise means if I do too much, I shut down. When that happens, I can’t move, think or speak easily. So, I have to avoid doing anything, lest I make myself even worse than I already am.

The stakes are high and the metaphors are serious. Approaching the one year mark, I’ve had to figure out how to cope with this. In that landslide, that storm, I’m like a tree blown over in the forest by secret forces. I’ve not quite fallen right down to the ground. Somehow, I’m balanced here, awkward, leaning on the things around me just to stay half-up. It feels like I could topple over at any moment, so I cling onto what I can: to the people closest to me and to the culture I still have access to inside my house. Friends and games. I think I am holding on to them but really, they’re holding me up. I hold on so that I can stay — stay here, stay breathing, and stay as normal as I can inside my head.

But you know, it’s all worth it because I’m a better game critic now. I’m kidding. I would sell my soul to the devil in a heartbeat to feel normal again, and my tachycardia means that’s really, really fast.

No, I’ve just been realising with this quiet kind of delight that maybe some good has come of this. And if it has, wouldn’t that be nice? Before I explain my workings out on all the game critic stuff, I want to pause to say the most important thing up here in the heart of the text. I only ever understood disability as taking things away from someone — as loss — and never as giving a person something new in return. But then, I wasn’t to know any different, looking in from the outside and now I know better. Approaching the one year mark, I’m finding things inside me that weren’t there before beyond this famous infection that changed me. It is a stronger kind of love for what I have been left with: for the people who have cared for me when I haven’t been able to look after myself, for the people who have remembered me even though I’ve had to withdraw from so much, and for the huge, constant culture of games that has kept me entertained and engaged and even social in spite of it all. I feel grown in good, hard ways. I feel grateful.

I’m glad I came back to games when I did. It happened just in time. And I’m glad bad change has led to good change in places like my writing. Even if I would never have chosen this path for myself, even if I did everything to avoid this happening to me, it still feels warm to see new growth budding carefully. There are small flowers growing out of the chasm of the earthquake and they are changing the colour of the land.

So, what made the flowers grow and what do they look like?

Nearly all of the things that I used to fill my time with have had to come to an end. I can’t stack the freelance work like I used to when I can’t even really have meetings. This time last year, I was living in a flat on my own, performing my disgusting girl boss life in a hyperactive world of my design. I used to have a lot more to do and a lot more on my mind. Games were quickly scheduled in when they became a part of that work. Press start, rush through, process, go. I was hasty and mechanical, and I know that looking back. But now, my time and my attention are my own again. I play a game from start to finish without interruption, more present, more open for what is about to happen. I have only the game in mind as it spirits me away and then I write about it with the same dedication, as if it’s the only thing that exists in the world (because sometimes that is close to true).

Maybe this specific disability has made me the perfect gamer, the ideal audience member. Where brain fog has ruined my concentration for most things, games have my attention in a way they never have before — and in a way art never came close to. The way I play games now is like I have the privilege of being a teenager again, like I’ve been sent home from school because I was too sick to carry on being there. I can’t do chores or useful things, and now the only responsibility I have is to rest. I also have greasy hair again, less money, and I’m more emotional than usual, so this analogy pans out. I even feel like I’m enjoying games like I’m a kid again, like games have gotten more fun here on the other side of becoming ill.

That could simply be because I desperately need to mainline fun in order to offset all these very serious thoughts I have. Is this me forever? Will I be housebound forever? Does chronic fatigue mean I’ll never be able to have kids? Have I seen all of the world I’ll ever see or will I be able to travel again? Oh, and what if my benefits don’t go through? Some Long Covid people have taken their own lives between the symptoms and doctors not knowing what to do about them. What do I need to do to not be one of them? I wring what fun I can find out of every single game apparently — that’s my answer. I cling to the story a game tells and I go with the cycle of joy it invites me to play through. I play games to overcome challenges I can actually beat, when so much else is out of my control. I need games more so I play them with a new fullness. It means the texts I’m writing now have gone beyond ‘what are games?’ to ‘can this game entertain me, save me, expand my world and my heart? And if it can’t, why is that? Let me figure out where things went wrong between us.’

When it comes to finding more fun in games than I used to, I think something deeper is going on. Yes, I am sick and yes, I have lost my independence and those are grave things. But because I am sick and because I have lost my independence, a growing part of me feels… free. Unburdened like I’m young again, there’s a freedom in disability that I was not expecting to find, and that freedom feels fun.

This is how I see it. As my life became more critical, everything became more surreal. As things began to really matter, they stopped meaning anything at all. And as my body has deteriorated, I have laughed at myself more often. It’s the whiplash, I think. It’s the nonsense of philosophy, consciousness, health, and the way nobody knows how we are alive in the first place. It means there is something funny about being in a body that has stopped working because bodies are supposed to work. As a writer, it is a little bit funny when my words slur out my mouth like typos because I am supposed to know my words. It is even funny that in 2019 I travelled to 30 cities around the world but now it’s a big day if I make it to the lamppost at the end of my street and back. I thought fun and disability were two ends of a spectrum — I didn’t realise that disability might summon fun closer like this. A small part of me is worried that writing about them together like this will be a bad performance of my disability, like it might undermine the depths of fatigue and chronic pain I have been suffering with. But I’m very much stuck in the 'sometimes, you just have to laugh’ approach to coping and at least I’m having fun with it.

This quality has come with me into gaming and into my writing on games as well. Playing with fun in mind sounds like an obvious goal for a game critic, but I came from art criticism didn’t I, and no one was having fun over there. With more focus on fun and how space for fun has been designed, I think it has sharpened my writing and just helped me make more sense of what my job is here. When I open a blank page, I have a place to write from now. And that’s true even if it means writing about how a game challenges what it means to have fun, especially when it comes to tough stories and violence. Or, why something doesn’t do anything for me but how it might work well for other people instead. There is a lot of intricacy in trying to communicate these thoughts clearly, whilst also writing in a way that keeps my own subjectivity front and centre and honest. But that’s another thing about becoming disabled — after months of struggling with my own comprehension and speech, I’ve never cared more about trying to make things readable and straight. And I’m sorry I didn’t care more about that in the past.

I am guessing that people who don’t read my work regularly will think that as a ‘disabled game critic’ I write about accessibility in games, and I don’t — and I should. I’m sorry I didn’t care more about accessibility in games until I needed accessibility menus for myself. I imagine that as I learn more about what I need for my body outside of games, I will know what to look for inside of them too, and then it will come through in my writing.

Sometimes, I feel so floored by these symptoms that I forget there are things in the world that can help me. I forget painkillers exist, mobility aids, baths, treats, reality TV. It sounds like a logical move that if you are sick you would do things to make yourself feel better, but it really does get that bad. I reach points where I think all I can do is accept this, and it takes other people with better energy to remind me there’s another way. I feel the same with gaming right now, but maybe I can aim to be someone who guides players with chronic fatigue in the games that they play so others can find comfort and fun in this state. What is inaccessibility if not the biggest buzzkill in gaming?

Well, disabled for now or forever, who knows. I write with stronger feelings in my chest than I used to because I need the culture I spend time with to really deliver; to do its best. One of my goals for this year was actually to try and get review copies of games and then release texts when embargoes were lifted in line with other publications. I do not have the energy and I do not have a reliable body that can keep up with that pace — and that’s okay. I realised that I don’t care about racing to play the newest games and I don’t care about having the hottest takes. After so long away, there are generations of games for me to catch up on, plenty of games to think about and find fun in. I’m working my way through them one by one in the reviews I post on The White Pube, and I’m really enjoying taking myself on this adventure. Here for a good time, a slow time, a time I’ll never forget. Becoming disabled has changed me but I hope you understand now that it’s not all bad.

If you’re here at the end of the text, please comment a controller 🎮 emoji on our Instagram or share the text with a controller 🎮 emoji on Twitter