For 5 years, we’ve been giving £500 a month to a creative in the UK whose work we wanna see more of. Grant #062 goes to yasamin ghalehnoie, funded this month by Holly Gramazio

bio

yasamin ghalehnoie, ghalenoii, qalenoii, is undecided by the incongruity of vowels in translation. born in tehran and intermittently based in london, they write (or not), walk (a lot), maldigest culture (everyday), make prints, perform and teach, among other things sweaty and silly.

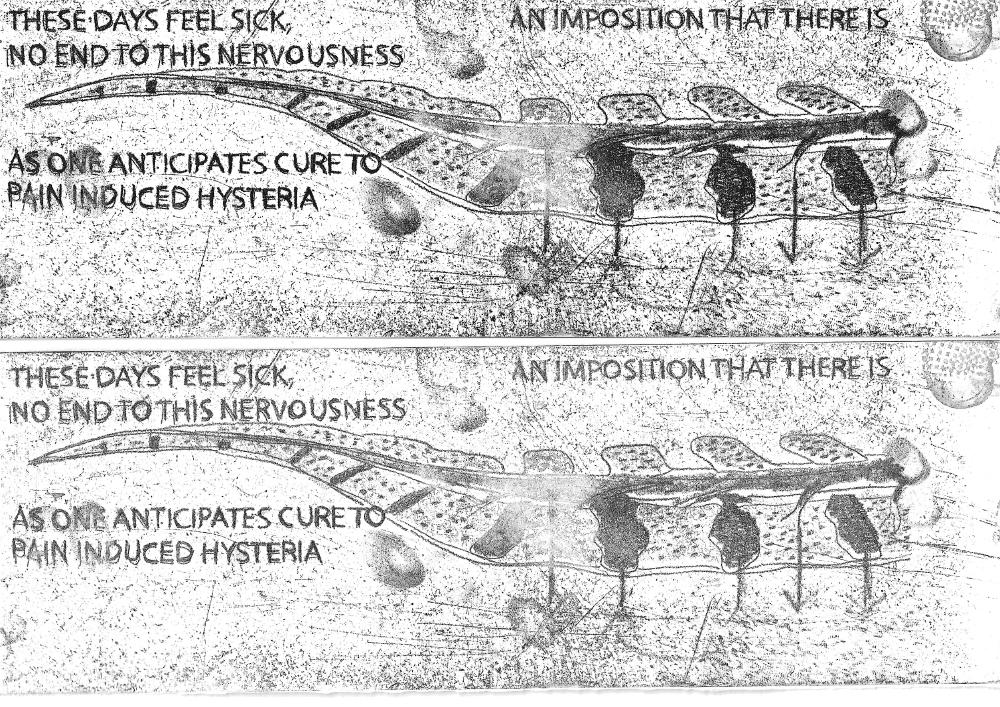

they are curious about the connections between nervousness & nerve damage and the biomedical underengagement with the distressed angels of history. affected by the inadequacy of words or meaning, or both, their most recent obsessions include staying on Santoor (iranian stringed instrument) after a decade long hiatus, and experimenting with etching (a printmaking technique using chemicals to bite into metal plates) to contain and corrode the residual mundanity of going mad.

their writing and works have appeared in Sticky Fingers Publishing, Errant Journal, common/play\grounds, RCA Cassette Projects, Weird Economies, Radio Alhara, IAWIS (forthcoming), Cafe OTO, Peer Gallery, Mosaic Rooms, among others. they have been a resident at Writers Room (forthcoming), Delfina Foundation, UNIDEE, pirate.care, Materia Abierta, 421, and Documenta Fifteen. they hold an MFA in Fine Art from Goldsmiths University, and are an associate lecturer at the Royal College of Art.

the grant

This month’s grant is funded by Holly. If you wanna donate to keep the grant going, please email us (info [at] the white pube [dot] com) & please find previous grant recipients plus FAQs here