I'm hungry

ZM

I think it is boring to say Ramadan is difficult for Muslims who have or have had eating disorders. It is boring because it is too simple. It is also incorrect. If I have one special skill, it’s an ability to endure the experience of hunger. I can take pleasure in it, I can enjoy it. But I don’t think I should. So it’s a dark and secret kind of pleasure, a special one that only I can understand in relation to myself. I have this ability dormant within me, but now I am better I haven’t had to exercise it. It feels foreign or nostalgic, and in that distance I think I am able to see it better. It is aimless, maybe. Maybe we give it meaning, shape, endurance. Maybe it is empty too.

It’s been a while since I’ve been hungry. I eat my meals on time, clean plate ranger, even if I’m not in the mood for it. I eat as routine. Every morning I have 30g of granola in a little mug with some oat milk. I eat the chocolate chips first. If I run, I add 18g of vegan protein (chocolate flavour, of course). I have my lunch at 1pm on the dot. I put it in a little bowl my Mum got me for Christmas in 2020. She said it was a happy bowl I can only have happy meals in because it was very expensive considering it’s only one single bowl. I sat next to her on the sofa while she scrolled on Anthropologie, John Lewis, Arket, Habitat, Oliver Bonas. She showed me the options: Japanese rice bowls, hand thrown cereal bowls, a bowl in the shape of a lettuce leaf, stoneware pasta bowls with special textured glazes, dessert bowls with little cats hand painted around the side. She’d open them in a new tab and zoom in, each time saying * ‘how happy do you think this bowl looks? On a scale of 1-10?’* I have a snack at 4pm, without fail. I get headaches if I don’t, and I start to feel like a limp spinach leaf, wet and floppy against my plastic packaging. Mostly it’s an apple, but sometimes I have a little chocolate or 2 biscuits. Dinner is my favourite meal of the day. I try to make sure I have something I actually want.

I have stopped cooking for myself though. Recently, I have been finding that difficult. Maybe it is because I have slipped into routine, where there is not much space left for desire or joy. I just need to get meals eaten and out of the way. I tick them off on a mental list and congratulate myself each time for a hurdle cleared and a job well done. I don’t think joy has disappeared entirely, it has just become smaller. I still find happiness in little things. I told my flatmate I liked a specific kind of bagel one time, and now she silently leaves them in the kitchen for me every time she goes to the shops. We break off bits of chocolate to throw into each others open mouths from across the living room. My sister makes my favourite fried rice for me when I visit, she lets me have the extra crispy bits. They sell chocco pies in Tesco - did you know??? It’s been so long since I went on holiday, and the thing I miss most is having crisps in a foreign country. After my long runs at the weekend, I make a jarg vegan McMuffin with Linda sausages. I think about it at every kilometre and mile mark, spurring me on because - everyone knows - running makes you hungry. They call it RUNger, that next level post-run hunger and -

Ahhhhh, but it’s not enough. I know it’s not enough. I don’t want to cook for myself because it is such a silly and useless kind of labour. Such a time sink and I already do the hard work when I shovel it all into my gob at dinner time. I have to eat on time, regardless of whether I enjoy it or not, because I don’t want to be hungry. I am Fixed™️. I eat my daily 2,500kCals without even noticing or actively counting them. Hunger has no space in my life anymore, it embarrasses me. They say, * ‘recovery isn’t linear or finite!’* and it makes me want to scream because I want to prove it wrong. I want to run far and eat on time and bang out my ab circuit without ever thinking about how my ribs feel, pressed up against the soft mat underneath me. I will be linear, *my* recovery will be finite. I am an unstoppable force, I go only forwards. My body is a kind of butter; it can stretch out and slide along a surface, leave a trail like a membrane, spread thin against wherever it touches. I clock up the kilometres and the miles like they’re nothing and every time I stop I think * ‘but I could go further, still’*.

I can be hungry, easy. I am just scared of it. I am scared of hunger because I don’t know what it’ll do to me, mean to me, how I’ll feel at the end of it all. I am scared to test out the stability I have built up around myself, I am scared to find out how fragile it is. But now, and for the whole month of Ramadan, I am hungry all the time. Hunger used to be familiar and banal to me, and now it is this huge gaping unknown, and I’m scared of it. So I need to recalibrate my relationship to hunger. I need to puncture the skin around it so it deflates. It is a normal thing that people experience everyday, people write about it, think about it, depict it. It is a representable Thing. In representing it, it is something we can give shape to and understand.

In A Hunger Artist, Franz Kafka tells a sad short story about a sad life. It is only sad because it is on the edge of a sad truth. It tells the story of a hunger artist, a performer who fasts for an adoring crowd. He was once at the pinnacle of his craft, held back by the limits placed around him. Back then, he was watched by these fascinated spectators and constant observers, always on hand to make sure he wasn’t secretly eating. But they didn’t get it, he’d never cheat. There’d be no point, the only person he was really trying to prove anything to was himself. And anyway, he could fast for longer than they would let him. He was dissatisfied every time he was made to eat. Eventually the appreciation for hunger artists died out, and he joined a circus. In this circus cage, there are no limits. He’s finally able to achieve his dream of fasting for longer than he has ever fasted before. But no one cares. Finally a supervisor approaches, asks him why he’s doing this. The hunger artist whispers in his ear, ‘because I couldn’t find a food which I enjoyed’ and then he falls down dead. He is dead, dead and hungry. They clear up his body, and put a panther in the cage instead. The crowds gather around the animal, adoring and lingering, enthralled by its power and fury.

A wave swept Europe in the Middle Ages, women starving themselves and refusing all food except for the Holy Eucharist. Now they call it anorexia mirabilis, holy anorexia. Back then, they just called them starving girls. Refusing food was the only way women could experience the suffering of Jesus, and in this shared pain they could be closer to God. Saint Catherine of Siena argued that it was about the separation of body and spirit. Physical, bodily hunger was replaced by a hunger for God that could only be met by this act of asceticism. Columba of Reiti believed her spirit toured the holy land in starved visions, she was communicating with God himself. This was productive pain, suffering purposefully, with intent. It was a sign of sanctity and purity, godliness.

Of course, hunger is a political tool too. I’ve never understood hunger strikes, because I think it requires a powerful entity to care about your individual wellbeing. But every time I google HUNGER, the 2008 Steve McQueen film with Michael Fassbender comes up. I remember watching the scene where he speaks to the priest with slow quiet tears streaking down my face. Because although I can do it to myself, I cannot watch someone else starve. Maybe it’s not about a powerful entity being made to care. I guess there is also something about hunger being appalling to watch. It is sombre, but it also becomes embarrassing for the powerful entity, a grotesque fate that they are directly responsible for. It asks for silence.

I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about something I glossed over in Eat the Rich. That bit from Ruby Tandoh’s Eat Up; ‘when Judee Sill sings about the gap between her spirit and her body, and the hunger that seeps between, it isn’t some dream of a bodiless existence. Sill doesn’t want to let go of her earthly roots, or the unavoidable hunger that we feel as human beings: she feels every last pang of that hunger, and she cherishes it. The wonderful thing about allowing yourself to feel your hunger - whether that’s the hunger that Sill sung about, or a more physical gurgling - [raging] in my guts - is that it reminds you of the distance between where you are, and where you want to be. When you say ‘I am hungry’, you might think you’re just talking about wanting another pack of Malteasers, but what you’re really saying is that you’re alive, and that you want more, and that there’s no pleasing your soul until your body has been appeased. You are myth, intestine, splendour, fart, divinity and heaviness all at once.’ I don’t know if I understand or feel the extent of that yet. It feels like a kind of smooth, limitless fiction. Maybe I just have to lean back and hope it’ll be there to break my fall.

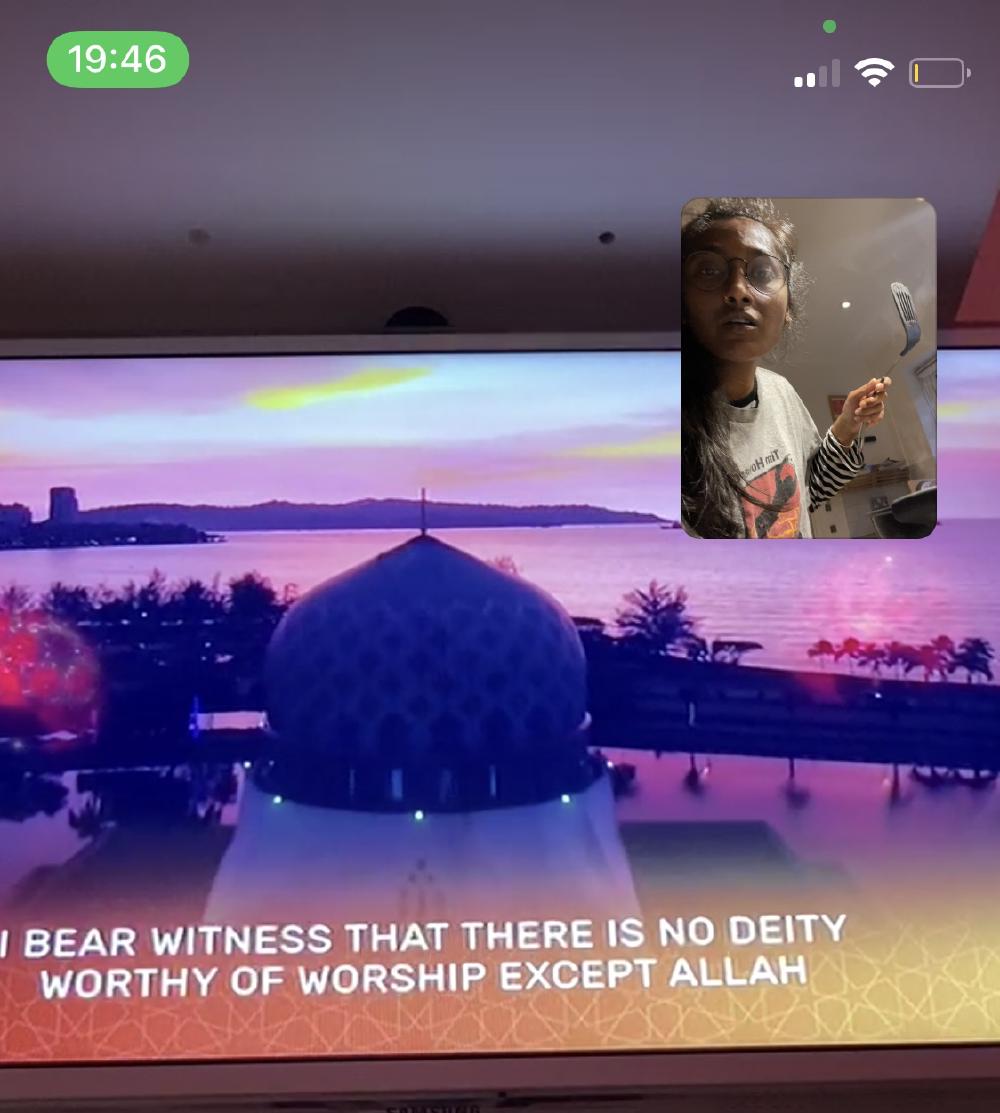

I fear God. When I am hungry and I exit my body, I am reminded of how flimsy this human form is. Bodies are fallible vessels and this world is an illusion, even though it is a beautiful one. Maybe there is something powerful and emotional in the experience of hunger during this month. Maybe there’s something in universality or ubiquity; we must all seek forgiveness in the same way, according to the same rules. When I wake up for suhoor, I look out my kitchen window to see if I can spot any other houses with the lights on. I am comforted by the fact that there are millions of us, all hungry together. My hunger has always been so lonely, but this is different. It’s a collective hunger; for food, yeah, but also for closeness with a higher power. The Prophet (saw) said that during this month the gates of heaven are open, and I have always wondered what that means. Does it mean that God can hear our prayers more clearly, now that there’s nothing between us? The Prophet also said that everything we do is for ourselves, except fasting. That is something we do for God alone. It makes me realise how aimless hunger actually is. How it doesn’t make sense on the scale of an individual. It can only become legible if it is in service of something higher, bigger, more than just us alone.

These kinds of mornings are my favourite: when the sun is high and bright, but the air is cool against my skin as I cut through. I can’t hear my feet against the tarmac path, but I can feel the force of impact in my thighs as they flex. 2.8 kilometres in, Coach Bennett tells me to remember my breathing. He says I should think about what that breath means. I am alive. I am in a body. Praise god and remember that body. It is incredible. If you have a body, any body, it is alive and incredible. What a miracle! God bless our bodies. The sky is pale blue behind the clouds, and I am alive.