ROTLI

ZM

I was raised by a single mother, so I didn’t grow up with men in the house. If there are ever men in the house, it creates an unusual atmosphere; the polite vibrating air of having a guest. And we should treat guests well, I love the novelty of hospitality, so it’s never heavy when men are served. But I can see the lives my aunts and cousins live. They have men in the house. Their worlds are flat circles with their husbands and fathers at the centre.

My Mum grew up in a family with four daughters and two sons. Her and her sisters would come home from school every afternoon and make an assembly line. They’d make the dough, and then: one would pull off handfuls and shape it into fat balls, one would roll the ball flatter into wide discs, one would slap it onto the tawa and gently press down as it filled with air and steam, one would pull it onto a hot pile, swipe oil or ghee across it with the back of a tablespoon. My Mum tells me that these aren’t bad memories, by all means they were a cheerful production line. But one time I asked where her brothers were when they were doing this, and she laughed without answer.

Rotli as technology, rotli as vehicle, rotli as utensil.

When I left home for uni, I didn’t go very far. I only moved from North to South London, but being on my own felt like the best kind of freedom and the most natural destiny. I had always wanted to be an island, I had always wanted to cut off my ties and run, I had always wanted to be a cowboy and cowboys don’t have cousins and sad uncles whose interior lives are unknowably shallow. As a teenager, my extended family represented a flat circle with husbands and fathers and sons at its centre. My new flatmates were strange, but my favourites were two white boys from some miscellaneous countryside. It wasn’t actually that weird having men in the house; I loved them and we were friends. They’d buy me glasses of rosé at the pub, little treats from Pret (just because), rolled my cigs when my fingers were cold, and took care of me in small ways that I’d never thought necessary. They were my little family. When I started to miss home, London felt awfully large and the river felt awfully wide. I bought a bag of atta, a velun and a round wooden board and I started a one woman production line. I pulled off handfuls of dough that I shaped into fat balls, I rolled the ball flatter into wide discs, I slapped it onto the tawa and pressed down as it filled with air and steam, I pulled it onto a hot pile, swiped dairy free butter across it with the back of a tablespoon. I texted my boys, we sat down at our sticky table, and it never felt heavy that I had cooked for the men that were in my house.

Rotli as the moon, rotli as the plate, rotli as the crumbling stomach lining that comes back up in hot bile, flooding your nostrils.

Mum used to make rotli saak most nights. My childhood meals were well portioned plates; saak (for vegetables), yoghurt (for protein and fat), salad (for salad), and rotli or rice (for carbs). We’d come home from school, and while we did our homework on the dining table, Mum would be in the kitchen. We’d clear the books from the table and all sit down to eat together, and only then were we allowed to watch tv. I think it must have been the summer before I went to high school, but something happened with the child support payments or the money from my Dad. Maybe the divorce just got finalised after all that time, but all of a sudden, my mum got a full-time job. Now when I came home from school, the house was empty, and I did my homework at the dining table alone. We ate at different times, I made my own dinners. I can’t remember what anyone else ate, to be honest with you, but I was able to eat what I wanted because I was cooking it. Sometimes I didn’t want to eat anything at all.

Rotli as a kind of social body, bread is a body, rotli is bread, rotli is a sociable extension of your body.

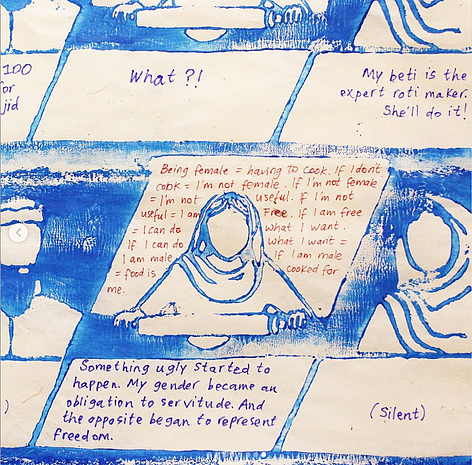

Seema is in Birmingham and I miss her and all my friends. She facetimes me as she’s going round ORT gallery; it’s Raju Rage’s show, Recipes for Resistance. She stands in front of a long wall full with a blue inky print; it’s an artwork by Sabba Khan. Sabba has carved the wood of a rolling pin, scratched in a long comic strip with three windows. From left to right: there is a window with a bearded shape of a man, a window with a young woman in a scarf (she’s rolling out dough with a rolling pin), and a window with another woman, but her scarf is draped more serenely. The rolling pin was used as printing block; to press blue ink to paper, rather than flatten fat balls into circles. There are three prints, comic strip style tryptic with narrative and plot. The first is oppressive, common for those with men in the house; a father orders more roti from his daughter without thank yous or pleases, a mother consoles but doesn’t question the directive. The second is discomforting, a state where change and upheaval are imminent; mother and father fall silent, fall back on absolutes and aphorisms while the daughter disintegrates in her centre. The third is naive and hopeful, the tentative future of an optimistic mind; the father & mother & daughter all pour out happy -isms that laud the rotli-maker as worshipped centre. It dissolves into fiction. I can’t see the words through the hazy resolution, so Seema reads one aloud in a flat voice. ‘Being female = having to cook. If I don’t cook = I’m not female. If I’m not female = I’m not useful. If I’m not useful = I am free. If I am free = I can do what I want. If I can do what I want = I am male. If I am male = food is cooked for me.’ I pause, I blink, I whisper: ‘it is the point in between, the liminal state of transition’. The circle bends at its edges. I feel it as it trembles.

Rotli as the verb - doing word, active, functional. Rotli as sinkhole, abyss, void. Rotli & saak — ah yes, the two genders.

I sit down to eat at our kitchen table. I always eat with the chair higher up than is comfortable, because I like to round my shoulders down, get a birds eye view of what’s on my plate. There are 3 little rotlis folded in half on the stainless steel thali in front of me. The saak next to it is still steaming gently, quietly. The rotli is soft and sad as it droops into its fold. I look at it, down on it, and in its silence I think it is looking at me. It scares me, even though I am above it at this vantage point. My ancestors had 4 kids by my age, moved across seas and mountains. But I am 26 and I am scared of bread. I don’t like eating alone because I dread the silence between myself and the food. I don’t like eating slowly because the silence feels longer. I don’t like eating quickly because I will feel sick. The rotli looks up at me, and I am sorry! Something passes, and I am overcome with a wave of sadness from all the tension that hangs between us. Steam, soft and silent, slow. I want to understand it, I wish it would speak to me rather than sit in this awful quiet. I want to ask it if it would cry for the hurt, when I move my hands to tear it in two.