Abbas Zahedi, <how to make a how from a why> @ South London Gallery

ZM

Emoji summary: 🌹💧🔄

Every morning and every night I wash my face with a small muslin cloth, and then I mist it with rosewater. I let the rosewater sit while I brush my teeth, and once I’m done I pat it in to my skin gently with the tips of my fingers. I don’t know if it does anything, I don’t know why I do it, or who told me to do this; but I’ve done this twice a day for at least 10 years now. I buy it from the Indian shop 5 mins from my house, I call the shopkeeper uncle, and I decant it into a little glass spray bottle (i don’t remember what it originally contained, the label was soaked off a long time ago). Rosewater is not a foreign object to me, it is not exotic, it is not romantic or beautiful; it is functional, practical, it is applied in a mist and it has a ~thing~ to be doing, regardless of whether I know what that thing is.

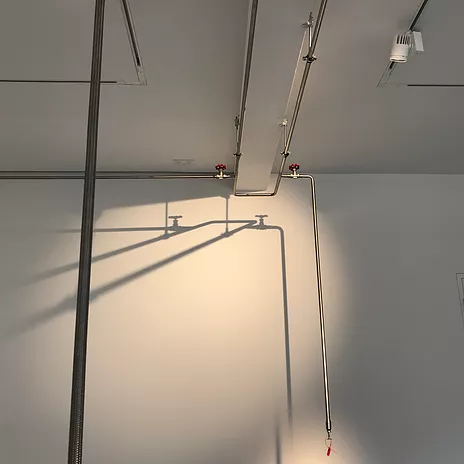

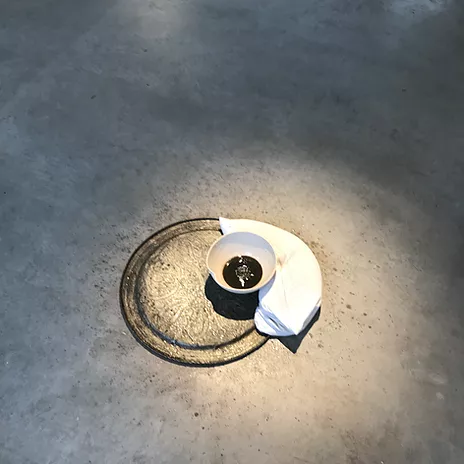

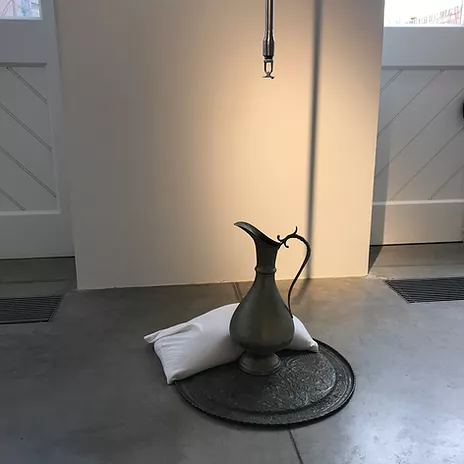

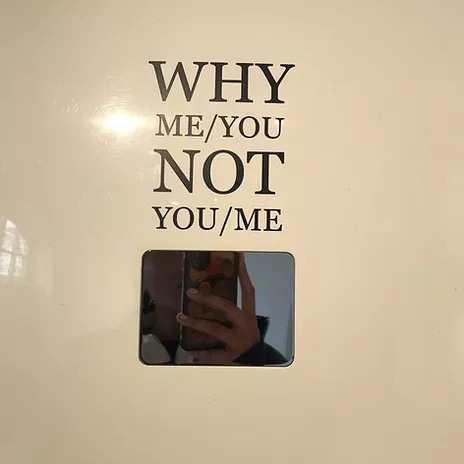

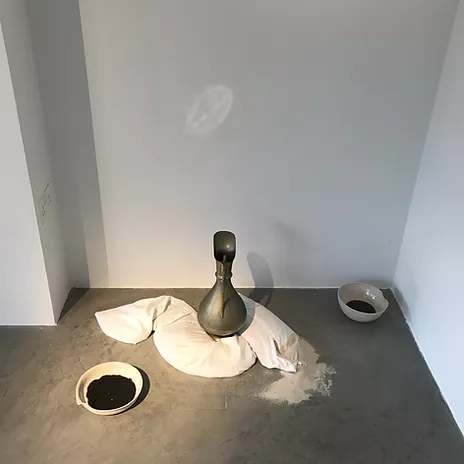

I went to see Abbas Zahedi’s show at South London Gallery the day after it opened, under better circumstances and sunnier skies. <how to make a how from a why> is the public moment that comes at the end of his 6 month postgraduate residency at SLG - in the Fire Station’s front room, with its folding window-doors and high ceilings. The work is slight, resting on that tender vibrational level: alongside circadian rhythm and dogwhistles. A stainless steel sprinkler system has been installed against the room’s high ceiling, some of the sprinkler nozzles jut down precariously to eye level, and they all leak. There’s a collection of brass jugs on circular platters, handmade bowls with finger shaped indents; by the time I’ve got there it’s past midday and there’s already a small pool of silty liquid in the bowls. On the far wall is a hand towel dispenser; one of the ones with the circular handtowels, the kind that are almost exclusively found in public buildings, where the towel is a fine, gauzy cloth that loops back up into the machine. There’s a mirror on the front of it, and a message that reads, ‘WHY ME/YOU NOT YOU/ME’ - I note that that isn’t posed as a question. It takes me a while to notice the cistern in the middle of the room (i get swept up in the intervention of the sprinklers above me), but when I do, I am alone in the room. There’s a hand pump screwed onto the top of it, so I push down on it with all my weight. I think I was expecting the water to come flying out in a rush, I was expecting something monumental to materialise from this, but the sprinklers only started to drip. Slowly slowly, I place my hand under one nozzle, for the drip to hit my outstretched palm, wait for a small pool to collect, and bring my hand to my face - I smell rosewater. Fresher, more concentrated, purer than what I mist my face with every morning and evening. I lick my palm; it was sweeter too. And slowly slowly slowly around me the bowls and the jugs were filling up with rose water, there were sandbags around one bowl, soaking up a spillage over - and the smell fills the room. Against the folding window-door, there’s a mad contraption wired up between the window and the shutters, playing a droney instrumental track. I stay for longer than I needed to be there for, in a haze, literally just vibing with the smell and the sound and the slow and consistent dripping of the sprinklers; but as I turn to leave I made eye contact with the exit sign - the same green panel but with an outstretched arm reaching down, hand waiting to scoop you up.

My friend, Amrita Dhallu, is my most favourite critic - we share a disdain for theory and a hunger for something real and tangible. When she says she values something, I listen intently. She said this was her show of the year. We speak often about my reviews, and she tells me truthfully when I write a flop (it’s my favourite thing about her); when I told her I was writing about Abbas’ show, she said ‘ok, but don’t talk about opacity again’. The backstory here is: when I wrote about Ima-Abasi Okon’s show at Chisenhale, Amrita thought I had used a conversation about opacity as a cop out, a way to avoid unpacking the work and interrogating it on a deeper level beyond face value (I agree, and I hate that review, for myself & for the artist). I am aware that this show (& Ima’s), happy on its vibrational plane, is further afield - a bit past the grasp of a first glance. It works in metaphor, symbol and signal; it conjures <something>, but it’s a something that’s abstract or a surprising and jagged shape. I’ve never ~pulled an artist for a chat~ but in my wanting to shed the skin of a badly written text in the past, I spoke to Abbas halfway through writing this.

We spoke around & though the work. About rosewater: his family back when were drink-makers - a ceremonial n spiritual role, for grieving or for ritual - and how rosewater is used to wash bodies before burial (so though the gallery smelled like clean-ness to me, to others it smelled like death). He spoke about how he wanted some of it to spill over onto the gallery floors, cleansing it, priming it, anointing it as a kind of corpse. Beyond material, into the personal and the political; SLG Fire Station used to be an actual functioning Fire Station back 200/300 years ago, when Victorian firefighting was a system rigged to protect property for those who paid an insurance; 10 years ago there was a fire on the Sceaux Garden Estate across the road, 6 people died, an inquest identified the council’s failings but Whitehall government didn’t commit any money to aid local councils in fire safety improvements; it is impossible to talk about fire in London and not think of Grenfell and the repeated failings the state engineers to ensure the neglect and murder of a specific kind of citizen; it is cruel and unusual to install a sprinkler system in gallery that used to be a Fire Station for the affluent, but to rig it so that it will never put out a fire, only drip drip drip the smell of rosewater and death and cleanliness onto it.

And then we spoke about lament: this work as a kind of monument to lament, as a lamenting body in its own right. Abbas said he wasn’t afraid of making something didactic, which I admire, but I don’t think this felt didactic. It might be a firm hand, planted feet, this work might be ~intentional~, but I don’t think it carries the stability of didacticism. In grounding this work as a work about lament, it is tied to an instability in its subject. Lament: a kind of passionate sorrow or sadness, but a verb. Maybe in its excess it is tied to the irrational body; racialised, gendered, made radical or unstable. Maybe it is exactly that; that instability; lamentation is that abstract feeling, the volatile rather than the quantifiable solid. Maybe that is what I would’ve relegated to the lumpy opaque; an unknowability in irrationality, grief, spiritual or mystical excess and transformative anger. On the back of the handout is a quote from <on lament and lamentation> by Gershom Scholem, n tbh skim-reading the essay only made this feel more tangled, but there was one bit that stuck: ‘lament is nothing other than a language on the border, language of the border itself’. Lamentation presents us with a phantom category, a new and sticky liminal language that obliterates as it moves. Whether this show laments the failings of the state in the face of individual liberties, needs and assurances // or whether this is a more discrete focus, of personal alienation within the 4 walls of an institution - I don’t think having a fixed vessel to receive this actually matters. It provides a system to bear the weight, to cleanse yourself through it, to ascension, to death.

There is something about this work as a whole and complete system - hand-pump/leaking-faucet/hand-towel. It requires the body of a viewer, not just to activate it, but it centres the body of its viewer into a primacy. You are the centre of a system, it functions because of your touch, presence and weight, the art work’s entire system serves you (the tender service of drying hands), and at the end it reaches its hand down and offers you an exit. At first glance, its sparseness could (COULD) read as sculpture-bro minimalism, an austerity that only ever emerges at the sharp end of haughty condescension and a lack of generosity; I am glad to have burrowed through. This show takes these formal considerations of space, minimal-and-partial-liminality, obliterated-object, and it supplants them. It waves a firm hand at formal expectation and exits canon without turning. It centres a willing, consenting body; it doesn’t deploy you to its own end, it presents you with heavy affect, and it gently tells you that there is more than this - exit. I think that is the height of generosity and care: it is a tender fix, a warm hand, a sweet ghost, my show of the year too.

I went to see <how to make a how from a why> in early March, so i don't know it'll re-open when lockdown is over (whenever that is). I hope it does, and I hope you get to see it too.