Death Stranding: The Final Walk

GDLP

Emoji summary: 🆘😭👶🏻

At the beginning of the story, I left Capital Knot City. I walked out onto new land and it was raw and barren. I dragged my feet up a hill towards a huge grey incinerator. It’s where I had been told to go but I wasn’t completely sure how I should get there. They told me before I left that the incinerator had been built up there in the mountains so the chiral matter released in the smoke wouldn’t reach any nearby settlements: but their words did not sink in for me, not yet, and I was so uneasy.

The route was mossy and hard. There was water streaming between rocks. A deep, wet cut in the land. I missed a step, splashed the water. I carried on, I just went up and up. I tried to find a way through and at one point I had to climb with my hands. Slow, bent over, heavy legs. I was carrying a great package with me: I was carrying my mother. She was dead and wrapped in a white body bag. She was strapped tightly to my back. I had my order, she was my order; dead weight making me tilt to one side and then to the other. I tried my best to keep my balance but it was difficult. Dead company in a dead country but at least she meant I wasn’t quite alone.

I didn’t quite know which way I should go to reach the destination; and I was unsure why I had to take her at all — and like this, on my back, on my feet. Secretive, desperate. I fumbled my way there.

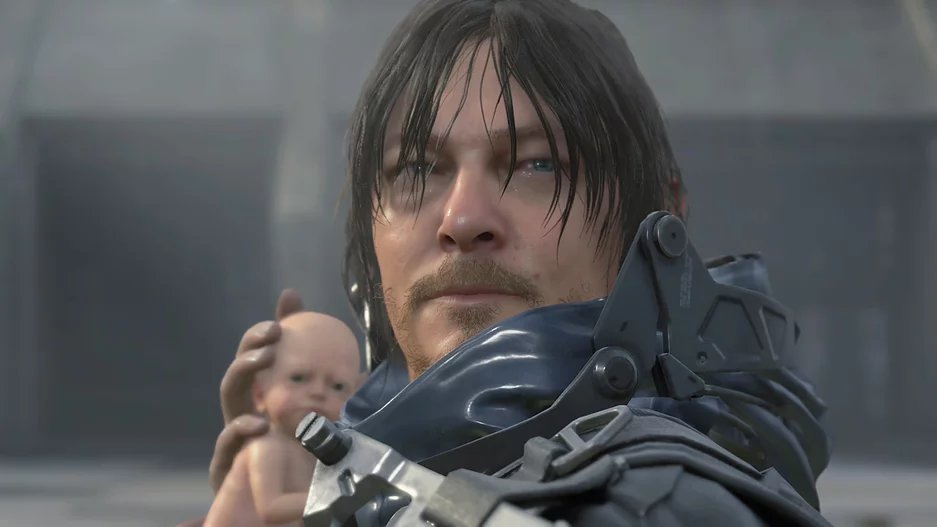

When I reached the blanched pyramid of the incinerator, I hurried inside. I checked in at the Access Terminal which slid up from the ground to greet me as I approached. I placed my mother’s body onto the cremation platform, making sure to be careful as I lowered her head down. The platform dropped and a transparent screen closed overtop. I watched as flames spiked along the edges of the tomb and nipped at her corpse. She was gone, the job was done, and outside it began to rain. I got a message to dispose of the other cargo on me, the Bridge Baby that Igor had left behind. But BTs had already surrounded the area — handprints slapped the glass and the floor around me. I needed this thing, BB-28, to get me out of here alive. I held my breath, I plugged it in. The Odradek spun on my shoulder and we got away, walking silently out of the storm that my mother’s burning body had summoned.

At the end of the story, I left Capital Knot City. I walked out onto old land and it was damp and barren. The area had only recently been flooded with the thick oily waves of a leviathan battleground. Dead fish had covered the place but now it was clear in the aftermath. I dragged my feet up the hill towards the huge grey incinerator. It’s where I had been told to go and I remembered the way — I had been here once before, a long time ago.

The route was easy enough but I felt sick. I had done hundreds of deliveries over much further distances than this — in the desert, in the snow. But this was the most difficult one yet because it was an order I simply didn’t want. It had me moving like a ghost up the hill. A silent, hollow drone. I was caught in the surreal state of a body moving on autopilot; a body acting in spite of itself, a body controlled by others. Yes, I was light on my feet but it was only because I was so empty. There was water streaming between rocks, making a deep, wet cut in the land. I didn’t miss a step and I didn’t land in the water because there were ladders where I needed them to be. I just went up and up, floating and in pain. The journey from here to there was a blur.

I had my order, she was my order; she was the dead, light weight that meant I wasn’t quite alone. Lou. I had been instructed to decommission Lou. I knew why the UCA wanted me to do this but I didn’t want to incinerate the baby that lay cradled against me. Her amber snow globe-home was glowing gold to signal an emergency; even in this state, she was the only sun in this sunless world. And I was supposed to lay her to rest? I was alone before and I’ll be alone again now. This can’t be happening. And yet I’m the one making it happen; I am inching my way up the hill.

When I reached the blanched pyramid of the incinerator, I paused before I went inside. I thanked Lou for everything. I thought about how far we had come to make it to this end. I remembered that she had saved me at this very incinerator when the timefall and the BTs had almost trapped us inside the grey tomb. But as I stood in hesitation, the game stepped in and took its fate out of my hands. I connected to BB-28 one last time and I fell into a long memory that showed me new truths.

I thought I knew my family but I saw how that family was not honest with me. My mother, Bridget, had stolen me and made me her own. She killed me when I was a baby — shots were fired through the body of my real father and then through me. She killed me when I was small enough to be held in just one hand. I saw her ka pick my body up from the beach and then drop me in the water so I would repatriate back to her ha on the earth. She changed me. She demanded I be kept out of my pod and she declared she would raise me as her own.

In that memory, I also spoke across time with my real father. He told me who he was. He said dividing people was the only thing he was ever good at; he told me I connect people instead. He said I was a bridge to the future. And from the past to the present, he touched my face. He held me as I held myself as a baby: a tiny, fragile doll in my adult hands. I knew who I was now, I knew why I was like that. I knew where I had come from and how I had been created. And in a slow-motion cellular wave, I felt myself catch up.

I came back to the present. In a dark flash, I saw flames close around the edges of the cremation platform. But the only thing on there ready to be incinerated was my cufflink: my connection to Bridget and the institution she had devised. At the edges of the screen, I saw fluid sprawling out onto the floor. The camera panned over to the mechanical womb that Lou had lived inside. It was open and she was gone. The glowing sun had been extinguished. And like a god watches over the living, I watched Sam try to resuscitate his BB. Limp, brittle, she was just a tiny, fragile doll in his adult hands. He tried to warm her up and move the blood in her feet, her hands, her chest, and through her tiny back as well. BB’s eyes were half open, completely blank. This really was the end. CPR did nothing. He just froze.

He didn’t want to be alone anymore; he didn’t want Lou to be alone either. He was supposed to be somebody that connected people. But time stretched out between them. Her umbilical cord faded into the undead pattern of BT anti-matter, glittering black in the air. He felt other beached things around them. He held Lou to his chest — to apologise, to say goodbye, to think about a life with nobody at his side — and then a small cry broke the silence and he gasped.

She would be safe. She would be his. They would both be free. Outside, the rain stopped and the sun came out. Lou was next to him, a quiet smile on her face. A rainbow arched across the sky, right-way up. Finally, their story was complete. The final walk was done.

There is a chasm between the two walks at the beginning and end of Death Stranding. At the bottom lies a vast story of human extinction and connection. Days, miles, drama, space, invented science and lore. I love it. I tried to pin words to the funny rusted aura of this game back in November and what I ended up writing was essentially a spoiler-free advert in an attempt to pull new players in. After countless messages and emails from people who trusted me enough to try it for themselves, I’ve been wanting to follow up with a second text: a spoiler text, a debrief, a chance to take our time and catch our breath.

I could write texts about how parenthood is represented in the game, or think aloud about its death loop and meta moments, and the aesthetics of the beach. I’m interested in the caricature of America it presents, and the rhythm of the gameplay as well. But when I think about Death Stranding, my mind pings straight to the same thing every time. The final walk. The crescendo of feeling squeezed in between the second and third credits. I want to write about it today to try and understand why that last sequence has been such a magnet for me since playing. I also want to write in order to honour the storytelling it achieves. That one walk bears the weight of the entire game like max cargo on Sam’s back.

An ending after the ending after we are made to think the story is done. We have already had our thesis, antithesis and synthesis. We have been given the mission to connect everybody, and we have gone on to a successful hero’s journey against the odds (against BTs, Mules, Terrorists, Clifford Unger, Higgs, and extinction). We have overcome the climax on Amelie’s beach by cutting her off from the rest of the network in order to contain the Last Stranding. We have saved those still living in quarantine on what remains of this country, for now. And so, beyond this point, anything that happens in the story is clocking in on overtime, at the very edge and the very end of five very long acts. Anything that happens is going to hit especially hard precisely because of its placement on the perimeter of the entire narrative structure — it is going to feel like too much.

By too much I mean, it poses a threat to the resolution the player has helped create. I didn’t want anything else to rock the boat. The game had started with some semblance of order, everything had then gone wrong, and I had bravely helped to restore things. Although the world had been saved, something still itched because I felt the story had resolved itself without resolving anything for Sam. When those first two rounds of credits had passed by on the beach as Amelie circled us and explained things, I opened myself up to the possibility that that was Sam’s ending; that he would be stuck here forever, a repatriate no more. It was a risk he was well aware of when he had come to try to stop the Extinction Entity… so, you know, maybe that was it. The end?

But the game continued. It entered its denouement. The word, from the French verb to untie, refers to the final resolution at the end of a story when complications in a plot are unravelled and loose ends are tied up. Not every story has a denouement — sometimes the climax is enough. But for Death Stranding, it comes in Episode 14: Lou, an ending tucked away like a body hiding behind curtains with just its feet poking out.

As the clock ticked over and the game carried on, I felt as though I was on the pinnacle of something. Would the game introduce a final threat that ripped apart the new world order? Or would it grant Sam the kind of peace that everybody else had received apart from him? I couldn’t ease the tension inside of me because I had no way of guessing which way the game would go — we had been thrown up, down and sideways into imaginary beaches, war zones, jungles, and underwater soul junctions. The game created a state in which I was well-primed to be oversensitive to any further goings-on… and then it handed me the final task. In Orders for Sam, there was Order 70: Cremation: BB. Please god, no.

The denouement picked at the scab that had formed over the whole story. I shuddered. I couldn’t kill Lou. We have just come all this way together, and she is only a baby. I have rocked her calm on mountainsides and kept her oxygen flowing. I have cared for her and she has cared for me. I so deeply did not want to believe Order 70 was real but all of the signs suggested BB’s cremation was exactly what was about to happen. There was no space for my own ideas of fairness, no space for ambiguity. The game was telling me it was time to lay her to rest and I had to quickly swallow that and get on with the job. I can talk now with hindsight on my side but at the time, I believed it was happening because the game made it seem that way.

First, it was an official order on the books like everything else had been. Second, when Deadman reunited Sam and BB at the exit to the isolation ward, their conversation did not sound hopeful in the slightest. Sam asks if Lou is dead, and Deadman replies that the ‘poor thing was never truly alive, not in this world at least.’ It’s not a yes or a no. He goes on to say, ‘The decommissioning order finally came through. Can’t risk necrosis. The body can’t stay here. I thought you might want to take care of it.’ It’s so casual — like, shouldn’t it be harder to talk about this stuff? He does add that, ‘You could try taking Lou out of the pod just to see what happens, but that would be in direct contravention of an executive order. And there are laws about that kind of thing now that we’re a nation.’ Deadman then ends by letting Sam know that his cufflink has secretly been taken offline so if he does want to try it, now would be the time.

I thought we might just do that, try breaking Lou out. Save our companion, finish the game. But a second later, outside the ward, Fragile appeared and the mood swung back to hopelessness once again. Sam rejects a job offer from her without a second thought. He says, ‘I’ve got no ties to anyone or anything. I might as well be dead. I felt like that when we first met in the cave, and I still do.’ She disagrees. ‘Don’t act like you’re the same person! You’ve learned how to touch. To feel. You’ve connected with people — with us!’ And sourly he replies that, ’Everything I touch, I lose.’ In those words, it is as if Lou is already lost — like she’s been hooked up in a private room and the computers have detected something beyond autotoxemia: plain death. It is as though Sam believes that as a concrete fact. It is as though it’s time we simply go through the motions and incinerate her at our earliest convenience, like any other order.

With this anxiety running through me, I left the Capital and made my way through the old streets of the city that remained. Was this really happening? Had Sam conceded a life alone? Was that decision out of his hands because Lou was already dead at this point? I didn’t know what to think. And then a song began to play that sounded like my soul vibrating. The lyrics and the softness of the singing made it seem, at first, like a lullaby: ‘See the sunset, the day is ending. Let that yawn out, there’s no pretending. I will hold you and protect you, so let love warm you til the morning. I’ll stay with you by your side, close your tired eyes. I’ll wait and soon I’ll see your smile in a dream.’ But it didn’t stay a clean goodnight, and in parts the song came off like an ethereal goodbye instead. ‘Feel the raindrops, the dawn without you. Watch that star rise, eons without you. I’ll stay with you in your mind every single day, I’ll wait and soon we’re stranded on the beach in our dream. We part too soon, but in our love there’s a truth to find. The end is new, and tomorrow we must reach far to be heard.’ It felt like the singer and the listener might be parted forever, not just for the night. Was Lou sleeping or was she really gone forever?

This song is propelled with a score that rushes and faints and rises and drums up a pure, distilled mood. It played as I made my way up the hill to incinerate BB and as I walked, the camera zoomed out. It was as though the camera was making space so the atmosphere the song had created could flood the screen. It lay down a completely elegiac mood and I did not feel optimistic. I felt like I was in mourning, and like the game was guiding me in how I should perform that state of being. I think a lot of credit for the emotion in the final walk should be pinned to this song, made for the game by Ludvig Forssell and sung by Jenny Plant. I feel weepy just thinking about it, even now. Like a smell can recall nostalgia, this song brings back the sadness of the characters in an instant. The specific strangeness of the game and its harsh values too. A lullaby or a funeral march? It isn’t clear. It continues the ruse.

I can be forgiven for thinking BB’s incineration was about to happen. All of this heaviness made it seem as though the best ending for Sam was no longer on the cards — that best ending being one in which he is set free from the grips of the UCA, and living happily ever after with Lou. Walking to the incinerator is a purposeful walk away from that happy ending. I found it so rough because in just playing and walking up the hill, I was actively betraying Sam and BB, the two characters I had spent the most time with and who I wanted the best for.

A life with Lou would have meant one in which Sam could have started to repair his soul after having lost his own family before the game began. Sam had married his therapist Lucy who was trying to help his aphenphosmphobia - the fear of both touching and being touched. She got pregnant with his child which meant she began to suffer from DOOMs by proxy, and this drove her to suicide. After the suicide, her necrosis caused a Voidout. As Sam is a repatriate, he survived while the whole area was obliterated. This made his phobia into a permanent armour or a repellant for forced loneliness, knowing if he ever were to fall in love again, he would not be able to have a child of his own incase the exact same thing were to happen.

Over the course of the game, Sam comes into contact with many people as he pushes to connect the chiral network. He spends most of that journey with Lou. But also Fragile, Deadman, Heartman, Die-Hardman, Mama and Lockne. He sees Amelie again after a long time apart; and there are other porters and preppers along the way. Eventually, we begin to see a change in Sam — he has a new openness to more people in his life. On the beach, he famously hugs Amelie to save the world. And once he is rescued from there, Sam hugs Deadman on his return.

This is why the final walk to the incinerator is a betrayal: the player physically moves the character forward as we feel the character’s life and their mind and their heart going backwards. We are about to be complicit in both Lou’s death and the metaphorical death of Sam, by taking away the child he needs. After all, he does not think he can have children of his own. But BB needs Sam as well. He has been the only one arguing for her survival. The worse case scenario here mirrors Mama’s death after the umbilical cord is cut and we learn that her BT baby had been keeping her alive. And in spite of this, I played on! I walked! I indulged the threat to the resolution, and the scab I had picked at once I started walking began to bleed all over me.

Once we have made it to the incinerator, Sam plugs into Lou — a final connection to say goodbye? In doing so, we travel through time into cinematics that reveal new details as final complications in the story are unravelled and loose ends tied up.

On the beach, Amelie had said to us, ‘Listen Sam, I was the one that brought you and Cliff together again. There was something I wanted you to know. You were never abandoned. And you’re not alone. Don’t you see Sam? You have to live.’ She brushes over this statement about abandonment and it is only in the denouement that we learn she was only able to bring him back from the beach after he was sent there by her own bullet. She never mentioned she killed his father a second earlier with the same gun. And yes, her words are true, Sam never was abandoned — the truth is, he was stranded instead. Cliff tried everything he could to keep Sam alive once he learnt that Bridget was planning on turning his child into a new form of technology. Cliff didn’t abandon Sam even after his death, though. He was so intent on keeping his child safe that his ghost was stuck searching for his BB ever after; and so tormented was he that he ended up hunting for BB in war zones that he felt matched the volume of his loss.

By making Sam’s past clear, the story reframes his future — it presents what it is exactly he should be fighting for. Sam saw what his father went through to try and save him as a baby, and now he knows what he must do to try to save Lou. He isn’t going to incinerate her, he is going to try to break her out of the pod. Otherwise, that metaphorical death will come true, and like Cliff, he could become a ghost missing his own BB and haunted forever.

These memories might also help explain Sam’s aphenphosmphobia and rejection of other people in general. Maybe it isn’t so much DOOMs-related as it is a condition that stems from this violent beginning to his life when his father and his stillmother were killed with him in the same room. He was then kidnapped by a woman who saw him first and foremost not as a son but as fulfilling one part of her extinction vision, however subconsciously she was operating — she also straight up drowned him as a baby to make him into a repatriate in the first place. It is unthinkably dark.

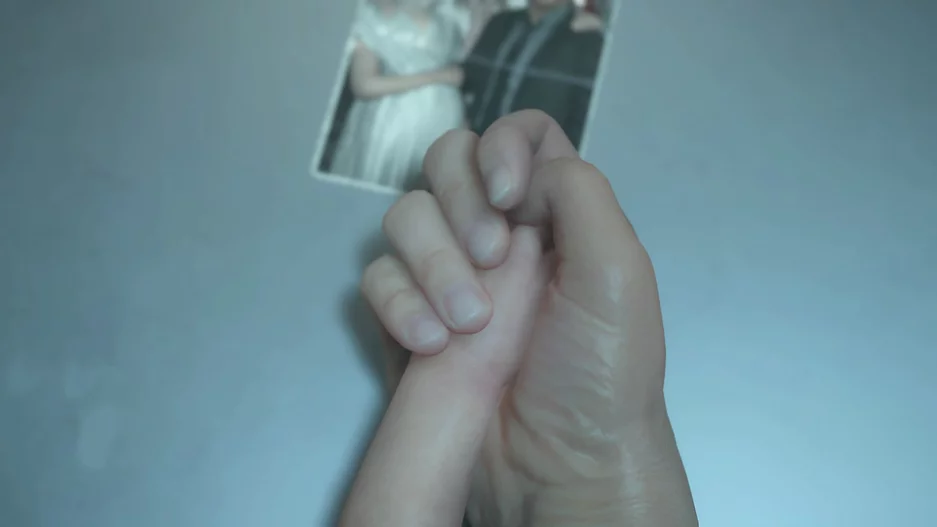

And so, when we snap back to the present and we try to revive Lou there is even more at stake. We finally understand how brittle and beaten Sam’s soul is. It is terrifying when BB is unresponsive because it teases at the imminent collapse of Sam’s character; and it is then the biggest relief when we hear her finally cry. It is warm and validating and a long-awaited true resolution for the both of them. It’s like finding something you had accepted was lost forever; it feels like coming home. The very final shot of the game looks down on Lou’s tiny hand over Sam’s as it rests over an old polaroid. The picture shows Sam smiling next to Lucy when she was pregnant. He finally has his family now. This is the end he deserves.

I finished playing Death Stranding last year but the final walk has stayed present in my mind like a strange burning memory. It is a huge pendulum swing between love and fear, hope and hopelessness — and it comes to us almost out of nowhere.

I was so attached to the weird world of the game that I read the novelisation afterwards as a way to spend more time with it. I enjoyed the books (the story comes in two parts) mostly because they helped me better understand the intricacies of the lore which, at times, had been a lot to digest. But I did wonder about people reading this version of the story without having played the game, because I felt that moments like the ending did not have as much momentum behind them having lost gameplay and participation.

I think the final rush of narrative is so intimate because it is delivered to us in the form of a game. Players (more so than readers) can note the difference between the first and final missions. By the end, players have gained hours of experience and they know how to move Sam correctly — how to walk, run, stop, balance, climb, and even jump when necessary. Players also get to a point were they know which way to go without having to look at the map; and an invisible network of others’ games mean there are ladders and climbing anchors to navigate the terrain more easily. Sam changes, so does the player, and therefore so does the game as well. By the end, we also have a better sense of the rules of this world and the value of places like incinerators. Early on, we don’t know the world or our mother well enough to feel attached to that initial incineration; and so, an awkward, empty walk makes sense. The final incineration is blasphemous in comparison because we are now moving with a confidence that further adds to our complicity. Readers would miss that; players, on the other hand, have to bear the unique consequences this medium can make us feel. The final walk presents a specific dissonance between what we want to do and what we have to do and it is a terrible complication that both the player and Sam share at the exact same time. It guts us. It is why this ending is so memorable.

The walk itself happens despite the reluctance of the player. We drag our feet through the wilderness of the rocky open world. But what happens next compounds everything. Once we are up the hill, the game switches from gameplay to cutscenes. We enter these flooded memories. I, for one, was glad the game took the wheel because I was just about to drive us off a cliff. Watching cinematics after playing through the terrible final walk takes this slippery moment away from us and dries it off. Cinematics confiscate our control. The story becomes more confident, already animated, written and decided. The story takes agency away from the player, and I would argue that that move feels good because it therefore takes any blame away too. This switch from playing to watching is part of the pendulum swing — it happens not just in the direction of the narrative but through its changing form as well. After the stomach drop the big swing puts us through during the gameplay side of things, the movie-style cutscenes that follow with famous actors and changing camera angles signals a return to familiarity and self-assurance in its actual storytelling. I think it eases us into the resolution. It gives us permission to feel relieved, and to let go.

All of this happens in roughly 45 minutes at the end of a 50+ hour game. It is so pressured and critical. It is dangerous, enlightening, and rewarding. I sometimes think about how low completion rates are for games, how much lower they are when games are as big as this, and how many people have gotten through the first walk and never made it past that point. But we have. If you have made it to the end of this text, I know you know the whole story. Like the ladders and signs and timefall shelters we share across our games, we get to share in this together. We made it to the end: we saved BB, we saved Sam. In spite of everything we faced, we connected them and as we did so, we connected with the game as well. I can’t wait for the Director’s Cut. I’m very ready to play this game again.

If you’re here at the end of the text, please comment a baby 👶 emoji on our Instagram or share the text with a baby 👶 emoji on Twitter