Mundaun

GDLP

Emoji summary: 🏔👹🤌🏻

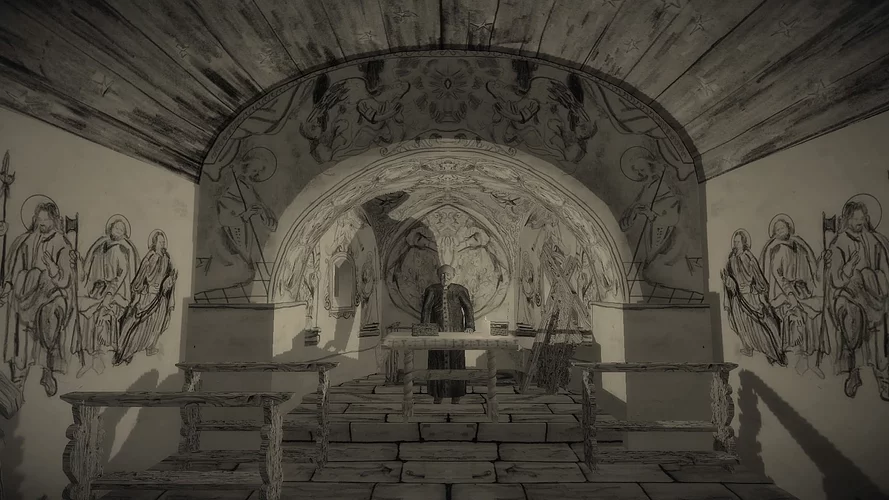

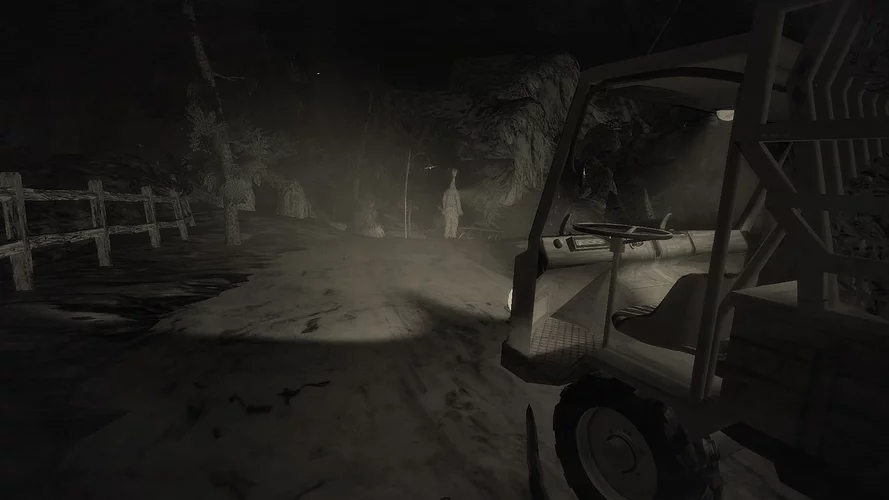

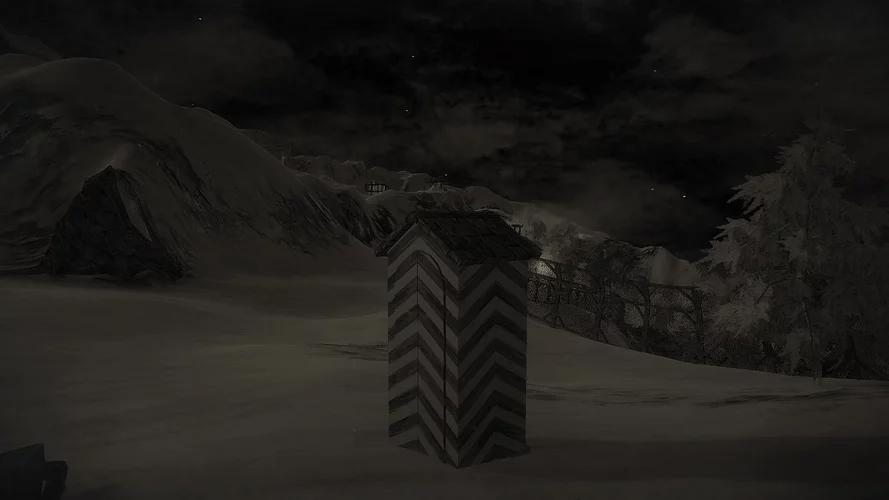

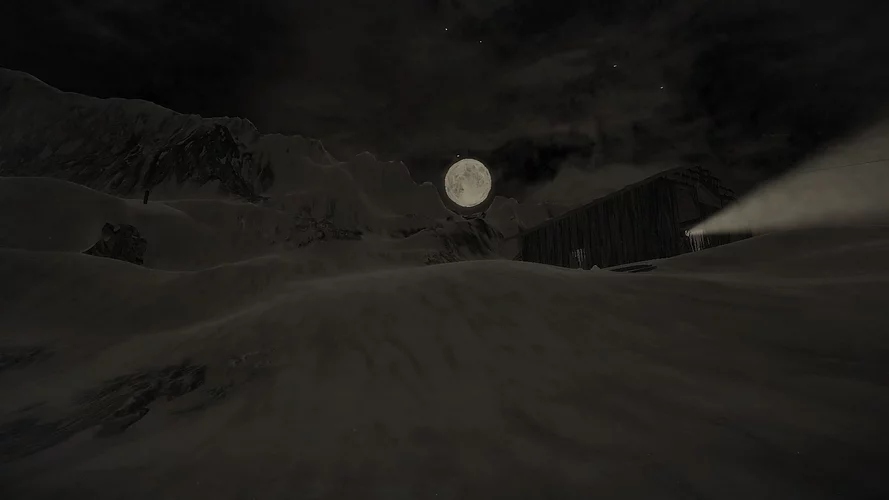

Mundaun, I’ve been to Mundaun. I’ve walked through barren mountains and into a glass lake. I’ve slept with spikes on my chest to protect me from the Devil. I’ve hiked under a full moon carrying a lantern that cast spiral shadows over the snow before me. There were scarecrows with broken ghosts inside their bodies and I tried to get away. The chapel, the angels on the walls — barns in the middle of nowhere. Basements, tunnels, bunkers. I’m still moving in slow-motion through them all, trying my best to hide.

It was just a story, one that had a beginning and an end like all stories do, but I think I might be haunted now. Even though I’ve finished the game, Mundaun has carried on in my dreams.

I love writing about the games that I’ve loved but they are also the trickiest texts to create. I know I need to find the other people who might love the game as much as I have, so we can share in the joy together, compare notes and recover. But I need to write about it in a way that means they can discover the game’s fullness for themselves. I try to use the space of the review to describe the mood and the imagery in an elliptical, whispered way. Edges only, scars; fingernail mark briefly on your palm. It’s hard to find the right balance of words when I’m writing about a game I have loved and I’m feeling that now for Mundaun.

Mundaun is a first-person horror adventure set in the Swiss alps and written in the area’s native Romansh language. It’s black and white, hand-drawn. The story is hard to face up to; it pulls on the stomach, the nerves and the soul.

It centres on a young man named Curdin. He returns to the canton of Mundaun after receiving a letter that his grandfather has tragically burnt to death. The quest is set: we play as Curdin, searching the valley to find out what happened. It is an investigation that screams and then unfolds through nightmares and other people’s memories. The gameplay is tense and sometimes opaque. It was the first game I’d ever played in the genre and it was the exact kind of horror I enjoy; quiet, gilded, animalistic, semi-religious and bleak.

The game’s creator Michel Ziegler took an old folktale local to Switzerland, gave new layers to the inciting incident and his own resolutions too; and then walked backwards and built outwards to create his own Mundaun. There is the overarching story of Curdin arriving on the mountains, and there’s the story of the myth within. A story within a story, Ziegler has locked the myth inside a thin cage like a terrible creature about to break free. The closer we get to it, the louder the horror becomes. It trembles, it speaks in tongues, and it moans to us in the language of the occult.

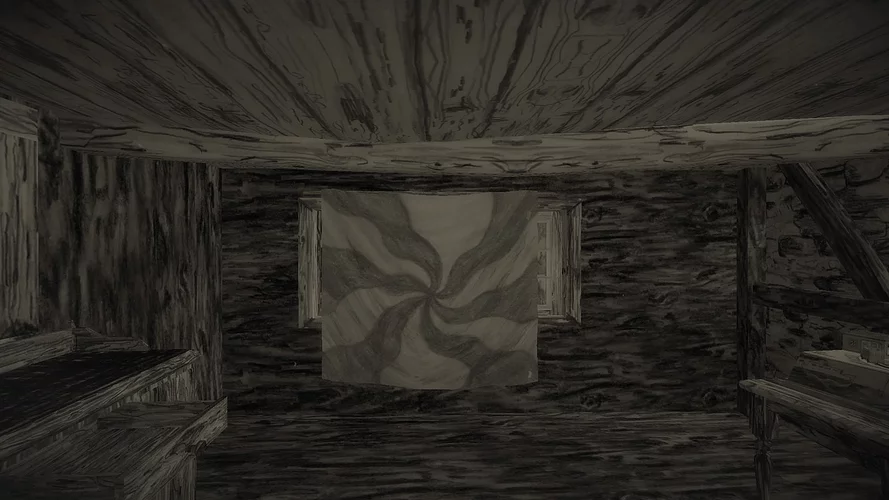

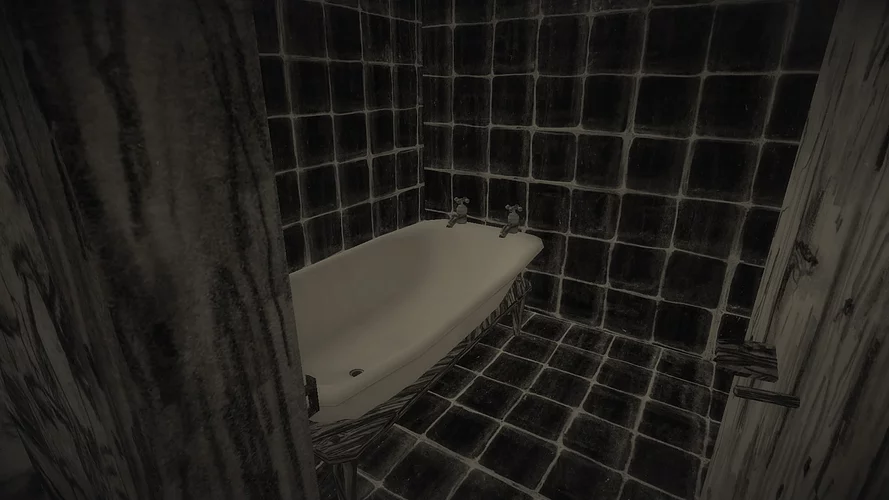

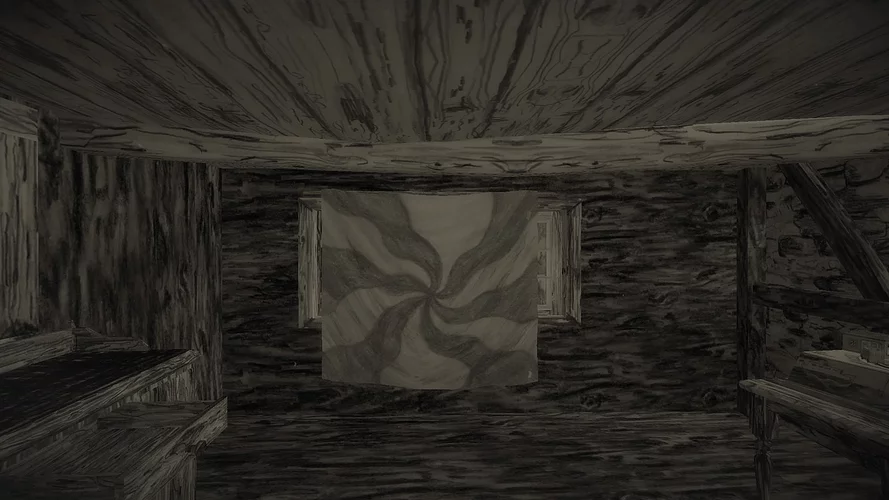

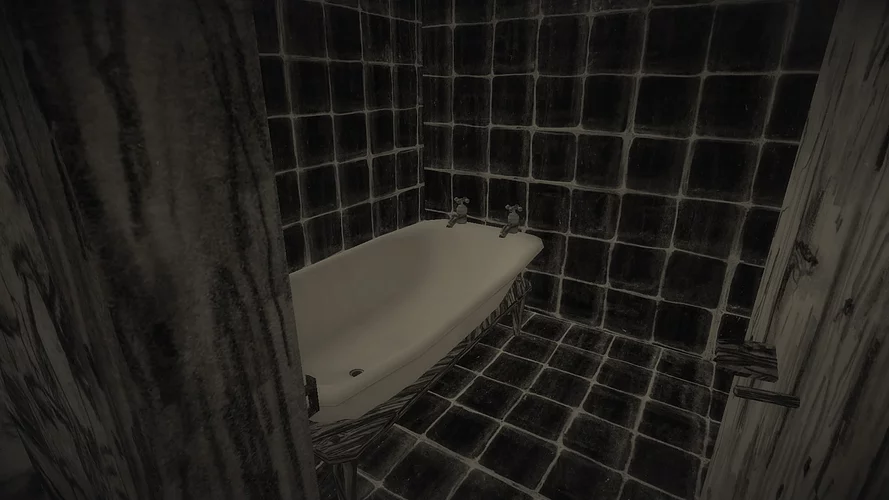

I can’t stop thinking about it. I can’t stop seeing it in my mind. I’ve never played a game with such a unique look. The whole game is hand-drawn and visibly so: monochrome, layered and worked. It is a feat. It is tangible. All of the characters, structures, items, interiors, effects and landscapes have been drawn with graphite on paper, scanned in, and wrapped around 3D shapes in the game’s engine. The way flat planes of hand-made marks and scratches have been stretched over natural forms only adds to the horror.

The drawing has emotion and movement. The curve of a rock becomes a vortex; the stiff face of a young girl looks old and new all at once (like the creepiness of a family portrait in early photography). It doesn’t look realistic, it can’t. But it gives a real aura to all of the details that Ziegler has packed in between the original myth and his own Mundaun. The symbols on houses and graves look painful. The mist in the distance rises up in spikes, and a two-headed mountain cuts against the sky. The jigsaw of different drawings feels dizzying, like we are walking through a helter-skelter geography; a dark sublime.

I think Mundaun is doing something similar here to the German Expressionist films of the 1920s, and I’m referring to titles like The Cabinet of Dr Caligari. They both use black and white designs to emphasise form, perspective, harsh diagonals, spirals, shadows and other patterns to twist and twist the mood. It is incredible to play a game with the same neuroses, and it is the perfect choice for this story. We take an oblique fall into the past and come face to face with an old curse; we meet elusive characters on the way to the truth; and we’re exposed to enemies so scary that at one point I shouted out loud alone in my room after turning around and seeing not one but two hay-men stood next to me in the dark.

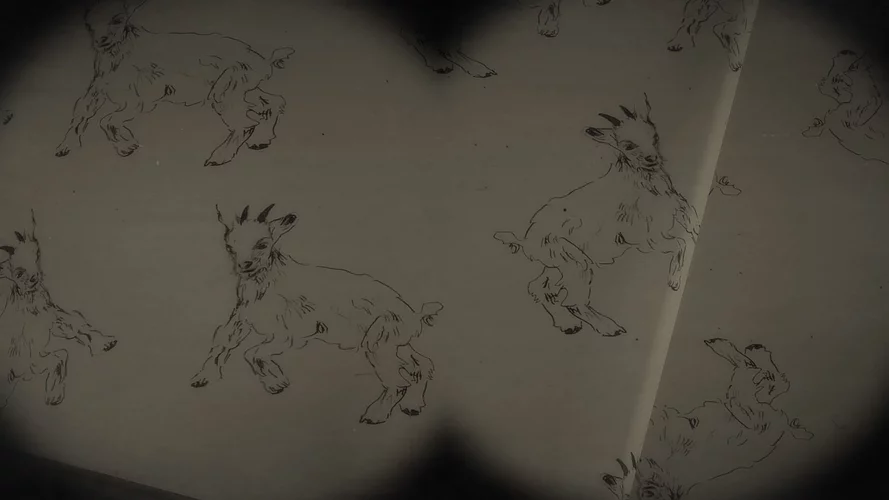

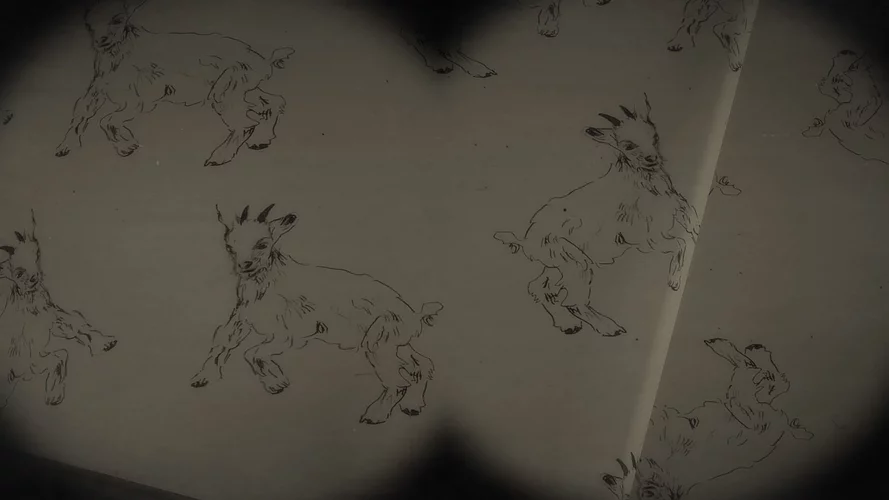

Plus, whilst the art style is unnerving on its own, the ragged atmosphere it creates is exacerbated by its place in time. We’re used to the smoothed out, commercial realism of other video games. We’re not used to this anxious, embryonic state. That’s not to say Mundaun looks unfinished; I think it wears itself very well. We can zoom in to see the carefully handled outline of a baby goat repeated on the blankets of a crib, or back out for the blushing graphite erased carefully into gradients for the skies. It is fantastic. It feels like such an achievement. And again, given the genre, it only helps that against every other HD full-colour sanitised game, Mundaun looks like an artwork that has deeply and consciously lost its mind. I was playing with the horror right there in my hands; I couldn’t pull away.

This review feels frantic. I just didn’t know where to start. I told you, it’s hard to find the words. I’m reeling off the back of it all. A review of this game feels too literal anyway, too day-to-day and narrow, when Mundaun goes somewhere else entirely. It goes somewhere thick and heavy, somewhere there is peril and divinity. Impossible to write about, better just to play. The words I’ve finally chosen for this review would all ideally overlap on the page, refracted and strange — I’d write them fast and backwards and hope you understand.

I hope other people play it. I hope the creator reads this review so he knows how grateful I am that he made it. The horror in the game is covered from all angles like a house of mirrors. After I’d finished playing, I dreamt about it over the nights and days. Rushed feelings, magic, elegiac space. Now that I’m coming to, I realise I want a piece of it for myself. Where are the prints, the figurines, the album releases and more? I want a memento of the dark arts, a fantasy keepsake, a little talisman to keep me safe. Mostly, I want ways to support more work like this being made. It was perfect.

Mundaun, I’ve been to Mundaun, and I already want to go back…

p.s. if you do want to know which myth the game is based on (spoilers, of course):

Mundaun takes inspiration from the folktale of the Devil’s Bridge in Switzerland’s Reuss valley. Legend tells of a bridge that was so impossible to build over the gorge that locals wished the Devil would make it for them instead. The Devil was conjured by their wish and offered the villagers a deal: he would make the bridge if he was allowed to take the first soul that crossed it once it was complete. They agreed but instead of a human soul, the villagers sent a goat across. The deal was sealed but the Devil felt cheated.

p.p.s. I've left pictures of the game beyond this point, mostly obscure and generic, but if you don't want to see them best to drop off now.

p.p.p.s. I've just posted a thread on twitter comparing game screenshots with film stills.

If you’re here at the end of the text, please comment a 👹 emoji on our Instagram or share the text with a 👹 emoji on Twitter

«««< HEAD

LAST 11 IMAGES ARE BLURRY

add-alt-text