Doodle House

GDLP

I signed up to The Agency a long time ago. A friend told me about it. Her friends had told her and eventually, everyone my age had signed up, which just felt inevitable and sad, like good musicians dying or knowing you’re never going to win the lottery. The Agency served both halves of society. Homeowners, who were the only ones allowed to have pets now, were also the only people who could afford to go on holiday. The Agency was part-travel, part-petsitting. It sold the upper-half all-inclusive packages so that they could continue to become better people than the rest of us. You know, for having eaten authentically; for having year-round tanned skin; for having seen the seven wonders of the world in situ and not on Google Maps (and for knowing that there were more than seven nowadays, because if you were rich enough, you could simply build a massive mausoleum for yourself).

I was on the bus to another gig. Gig? It didn’t even contribute towards the gig economy — The Agency paid us fuck all. Homeowners whisked themselves away on holiday and we got to take staycations in their stead. Because we had the privilege of staying in their nice homes for free, we promised solemnly to keep their dear pets alive. That was billed as another privilege by the way, because otherwise the only animal contact we had as renters was hearing foxes shag, avoiding the silverfish that come complimentary of the tenancy agreement, and being jump-scared by mice in places mice should never be (dressing gown pockets, for example. Always make sure you check).

It’s a little bit embarrassing to be a voluntary housekeeper and yet, I feel more embarrassed when I am at home. Not my home. I mean the home I am buying for somebody else. I’m embarrassed at myself for just agreeing to support this person’s buy-to-let fantasy. Like, I really did just agree to live in a falling-down house, knowing that I can’t ask the landlord to put it back up again without the rent going up in line with my requests. I have to keep my mouth shut. I have to listen to the foxes. I have to stop myself going round their house and putting mice inside their dressing gown pockets. So, I busy myself with other people’s real homes instead. Real homes.

Liveable in winter, a harbour in the summer. Dry and quiet all year round. Real homes with big fridges that are actually cold enough to keep food fresh long past its expiration date. Homes with kitchen islands, empire beds, underfloor heating, Molton Brown, and rain showers. Homes with surround-sound, plants that stay alive in the domestic climate, natural light, matching crockery sets, and plugs exactly where you need them to be. I stay with The Agency because it is more restful to live somebody else’s hotel-pillow life for a week or two; it’s the only kind of holiday I get.

I mean, it just feels right when there’s breathing space between furniture, like the space between art in galleries. I was trying to be an artist but I don’t think much about art anymore. It’s all I used to think about when I was younger but it’s hard to think about painting, or animals, or leaving the country, or the future when I have my hands full propping up other people’s hopes and dreams. I don’t imagine much will change for me. I don’t see how. And so, I barely want to mention the art thing. Like, I don’t even go to galleries anymore, although I do sometimes see art in the hallway galleries of homeowners. When it’s time to leave, I sense the world closing in on me. I just bus it from gig to bastard gig and I try my best to forget about what it is I used to want from life.

I got off at a stop in Kent, in a small town called Tenterden. I had my head down, flicking between Maps and Wikipedia; England’s small towns blur into one if I don’t make an effort to learn something about the place I’m in, and even then, it’s always the same story. Tenterden looked like a conservation area, twee and clean. Not exactly one of the seven wonders but it did get called the ‘jewel of the weald.’ I assumed that meant world and I didn’t agree; I imagined a local resident adding it as a tidbit to the Wikipedia page with a really smug look on his face. Maybe a councillor. Maybe he made it up for shits. But actually, weald just meant a heavily wooded area. The town was built outwards from a clearing in the forest where Romans would collect acorns to fatten up pigs before slaughter. Still, twee and clean.

I headed for the house, expecting a listed building, possibly a cottage. An old cat left behind by an even older couple who were on their annual Mediterranean cruise. I don’t know what rich people get up to, or what I’d do if I was one of them. People with holiday property bonds. Bonds, full stop. I had a vision of this old couple lathering their leather skin with olive oil and just absolutely sliding around their cabin, letting the waves knock them into each other over and over again. If I was right — about the age of the homeowners, not the olive oil sex — I was going to imagine they were my grandparents like I always do when the decor is a bit dated. I’d imagine they were leaving the cottage to me in their will. I just had to bide my time until…

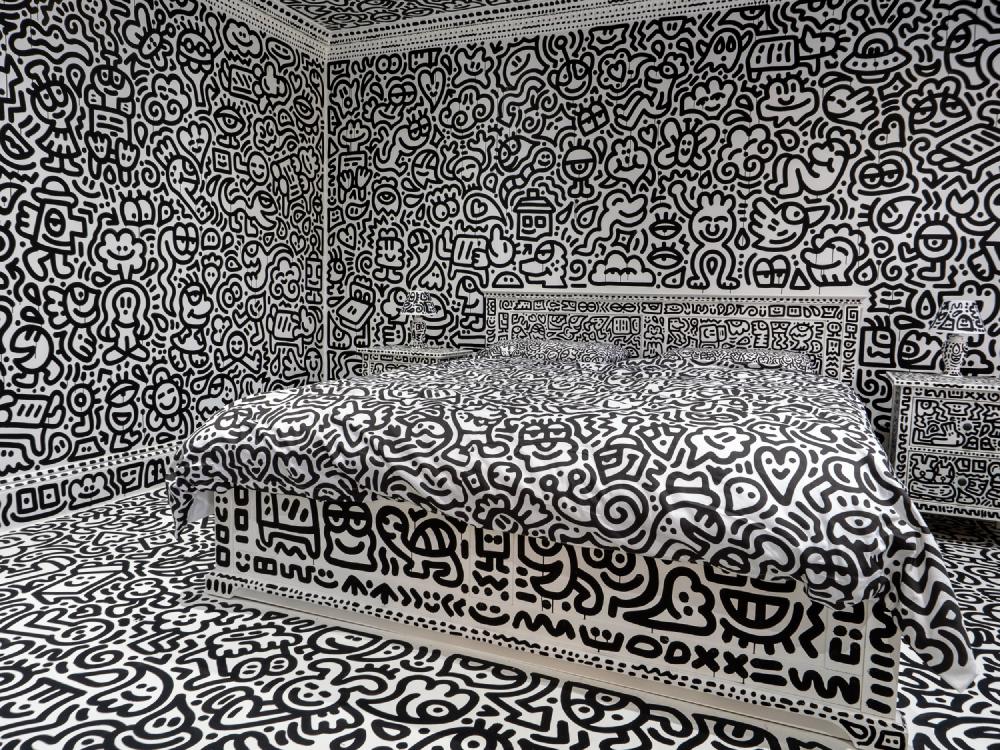

When I got to the end of the route and lifted my head, I thought I must be in the wrong place. This looked nothing like a home. It didn’t feel like one either. The world was now in black and white. There was a gated entrance and a thick layer of mottled black and white gravel over a drive leading up to a mansion. The facade was white, as were the garden urns, the front door, the step, the columns holding up the front-facing balcony, the window frames, and the Tesla parked outside. All white but the white was a base for an homogenous, thick black scribble over the top of everything. Everything. It was like a giant, intense toddler had gone ham while its parents weren’t watching. I could see hearts, spirals, clouds. Some arrows, crowns. Something that looked like a goomba — various shapes with legs and boots, and between them, more lines, more waves, more eyes. Mark, mark, mark, on and on. The brickwork had been spray painted close to the surface so that the ejaculate was dripping in places. It was a lot to take in but it also wasn’t?

I thought of Rola Cola, and with it, my guilt for only liking the taste of the real thing. Guilt without the commitment because I have not been able to decide if taste is a predestined thing inside of me (on my tongue and in my eyes), an acquired thing from growing up (I had parents once upon a time), or a doctrine I’ve agreed to (like paying rent, and looking after other people’s pets for no money). The style of the line-drawing appeared to be a knock-off Keith Haring, but it tasted wrong. My first thought was that the mansion must be a quaint Kent-based museum dedicated to the artist; who knows, Tenterden could have a decent Keith Haring fanbase. But then, that tidbit wasn’t on the Wikipedia page. Maybe it hadn’t opened yet? Maybe in preparation for opening, the museum had commissioned a graffiti artist to reinterpret Haring’s dense, modern-primitive style, which was itself a reinterpretation (or appropriation, or collaboration, or decimation) of the work of artists like Angel Ortiz; of molas textile designers; of Australian Aboriginal artists like Judy Watson Napangardi; and of French guys like Jean Dubuffet.

The drawing over the house got more bulbous the closer I got. The width wasn’t consistent, and neither was the spacing or the scale. That irritated me. Haring had always kept his balance, which stopped his artwork looking like it had come from the margins of a teenager’s homework. Walking up the drive, I spotted a duck and a flower in the scribble. Noughts and crosses. The edges of some walls had the suggestion of a meander, but the waves were interrupted by zig-zags and Unown-looking punctuation. I didn’t know what to think but I knew how I felt. I was unimpressed even though there must have been ladders involved. Unimpressed even though I felt like I should be — even just to be nice — because it was a mansion, and somebody had gone to all this effort to customise it. I guess I felt the same way you might react being shown an intricate, permanent and horrible tattoo. And then the person with the tattoo notices your silence, and they speak gibberish to fill the silence. The drawing was the visual equivalent of that; of stretching towards a word count. I wanted to turn right around.

I really didn’t want to sleep in a hypothetical museum but there was a pet inside waiting for me — and it wasn’t a museum. I checked the address. Somebody really lived here.

Inside, the drawing continued. Without the blue of the sky or the green of the grass or the scale of the air to offset it, the black and white was harder to bear. Every plane was drawn over. Every tile in the bathroom, patterned with the stuff. It was concentrated on plates in the cupboard, branding the cereal boxes and the bedding, and even vandalising the oven top. I had to look at the banal colour of my own skin to catch my balance. It was odd. The strict black and white design had the effect of a constant optical illusion, oppressive, meddling like a migraine aura; and yet it somehow achieved a camouflage effect, disappearing the objects in the house so that it seemed as if there were no chairs or tables, but only this constant drawing with the occasional shadow to frame it. It made the mansion feel very small, and it made me feel sick.

I just about managed to find a Sharpie-written note in the hallway that the homeowners had left for me. It was blending in with the table, and the wall, and the whole house behind it. The note read, Enjoy Doodle House. The dog is usually in the office upstairs. He doesn’t bite! Love Mr and Mrs Doodle.

I had to hold onto the walls as I made my way up there. I was scared the illusion was going to make me fall over, and if I did fall, I didn’t know how I would get back up. So once the stairs were over with, I decided to crawl; it was easier to look at one stream of dots and dashes, rather than having it flashing in my entire periphery. I crawled for ages trying to find the office, passing through one room where the lines had ordered themselves into clouds, another for splats, and a third for jigsaw pieces. I couldn’t find the office, and I ended up in the bedroom and then in the ensuite where I pissed bright yellow and decided not to flush, before slipping into the huge free-standing doodle bath for a rest. Didn’t turn the water on though — I was worried the paint would lift off the sides and dye me. No, I lay there in a cold sweat and got my phone out so I could google what the fuck was going on.

Mr Doodle was an artist. His name was Sam Cox. We were both born in 1994, which sort of made sense to me. The house was somewhere between Groovy Chick, etch-a-sketch, and alphabetti spaghetti, and it was shameless too; Sam Cox was a hardstuck millennial. I carried on. The man studied BA Illustration at the University of West England, which is where he began dressing in clothes covered in his own drawl. Art school is where he became this character. There were plenty of videos of him. He was very earnest in every last one of them. He spoke to the camera with the intonation of a kid’s TV presenter, often touching on his own man-made lore. As it happens, Mr Doodle wanted to doodle all over the world but his evil twin brother wouldn’t have it. Mr Doodle made a deal with the anti-doodle squad (lord help me) to leave the planet and draw somewhere else, but his evil twin brother chased him there. Something about his brother being jealous of him because he was just so good at drawing. I don’t know. But when Mr Doodle returned to Earth, all his doodles had gone, thwarted by the eraser laser. So, he decided he would have to create new doodles and trade them for things so that he could — again, I don’t know — build up the funds to go back to the paper galaxy or whatever it was called?

It came off like an act of self-mythology in order to make peace with the art market; I had more tabs open at this point and had learnt that Sam Cox was the fifth best-selling living artist under 40 in 2020. Naturally, he’d bought the six-bedroom house I was breaking down in for 1.35 million pounds — information that was easy to find because every major news outlet seemed to have done a feature on the building, including Architectural Digest and the BBC. All positive by the looks of things. Everyone just absolutely delighted by the novelty, with Cox explaining he’d been drawing on things ever since he was a kid so this was a dream fulfilled. The house had taken two years to complete. 401 spray paint cans, 900 litres of white emulsion, over 2 thousand pen nibs. He lived here with Mrs Doodle who apparently found the whole thing quite calming — this labour of love, this passion project!

I couldn’t stand it anymore. I closed my eyes so I could think.

I was obviously bitter. Taste aside, it seemed incredible to me that an artist could ever afford a mansion, never mind fuck one up for fun. The artists in my life are all people on the petsitting side of the deal. I almost forgot that rich artists existed. And I didn’t know if Mr Doodle came from money but either way, I was feeling almost betrayed — but it was a betrayal I didn’t know how to admit to, because it wasn’t fully formed in my head, just knotted like his drawings in my gut. I kept my eyes closed in the bathtub while I tried to catch the reason, and resented him for making me think about art. The feeling went a little like this:

When I was hesitating outside on the drive, it was because there was something dark about an entire building and its accoutrements covered in a wobbly black line, as though a great net had caught an animal that was, on closer inspection, already dead. I realised Mr Doodle had made a massive mausoleum for himself. But honestly, why shouldn’t he? It might be a better world if we were all granted a mansion of our own. Somewhere we could fuck up in our own particular way, with our own particularly fucked up taste. I was lying in the bath he had expressed himself in, thinking about how I am not permitted to stretch out with the same ease because the building I live in is not a building I own. The landlord won’t let me hammer into the walls to put up my family photographs because he only re-plastered it last year; the kitchen is one of the ugliest rooms you’ve ever seen, and the carpet is the colour of dried cat sick. If I had 1.35 million pounds to spare, I wondered how I would make a house my own. But I couldn’t remember how to use my imagination. It had been ground out of me. The inside of my head was empty, and that’s why I was so sad. I guess that’s one reason for the bitterness, and for some of the betrayal too. It hadn’t been worn out of him, I mean, his head was so full he had to empty its contents over en entire house.

This is when I got out of the bath so quickly I saw stars and had to resume my crawl. I was going to get fired from The Agency for doing so, but I also couldn’t stay here any longer without trying. I simply didn’t have a choice. I bumped my way down the stairs and went back through the front door. I shaded my eyes from the house until I found the garage round the back. That’s why the Tesla was parked out front. The buckets for the 900 litres of white emulsion had yet to be disposed off. I found some unopened ones on a shelf, a roller, and I hauled it back inside of the house. Dizzy up the stairs again, I went into the bedroom where Mr and Mrs Doodle dreamed, and where I was going to have to sleep tonight against my own will.

I just… I wanted us to all be in the same starting position before any of us got to make these kinds of elaborate, conspicuous statements. I know it’s just the way of the world, that there are classes of humans, and some classes of humans get to take up more space on the planet than others (a rock floating in space that belongs to no one) — and those others have to curl up small in a bath like a cashew lest they take up too much space. I mean, I was upright now. I was painting the bedroom, of course. Deleting the black lines so that I could see. All this indulgent shit seems even more indulgent given how unequal everything is. It becomes offensive. It becomes an intrusion on other people’s lives because now we have to know it exists; it looks so ridiculous that BBC News are obliged to tell the nation all about it, and the classes who don’t have mansions are cursed with the knowledge that an artist did this. It’s knowledge we already have, of course. We all know that some people own mansions, and we sort of know what artists stand for. But now it’s knowledge we have to feel, because an artist in a funny suit has taken the mansion noun and used his pens and his spray paint to turn the noun into a reverberating symbol. Into a material. A flex. An extension of himself. Like a god, an architect, a megalomaniac, Mr Doodle has made the mansion in his own image (never mind the fact it’s a borrowed image) and we watch the news from our rented homes knowing nothing of mansions or artists or gods. And we think, fuck off, and change the channel, and paint the bedroom back to white.

I lay in a trance, all the paint fumes, forgot to crack open a window. I thought about my bank account but there wasn’t much to think about, so instead I considered the right of artists, and people in general, to do whatever they wanted. I was flat on the bed now. Painting the ceiling had been really hard and I’d had to let paint drip over the bedsheets, which was fine really, because I wanted them white too. But now the floor was a wet paint-shop swamp and I was rocking around the room in all the liquids like the old people on the boat. Back was wet now on the wet sheets in the wet room, but at least it wasn’t a doodle room. I don’t know. My revulsion was useless, and also hypocritical. I would move classes if I could. I would let art help me in that move if it could. But I don’t think I would ever make the type of art that rich people would want to put in their houses, so where does that leave me? Covered in paint. Sort of satisfied by something I’d made. I should follow this man with my roller and reset the space wherever he went. I could think bigger. I could raze the house, and the whole town, so that it was a clearing in the forest again. Somewhere we could fatten pigs with acorns, and sleep under the stars instead of spray painted ceilings. My imagination was returning to me, and it felt like a surprise. I peeled myself off the bed and stood ankle-deep in emulsion to look at what I’d done.

My stomach dropped just a little; I realised I was the anti-doodle squad (as much as I cringed to myself, repeating those words in my mind). I didn’t think I should be angry with Mr Doodle for scribbling over an entire house he owned when ultimately I wanted liberation. I might cringe at the vernacular but actually, I don’t want to cringe at that or anything in fact, when cringing is just the body’s way of stopping us from doing whatever cringe shit we think will make other people think less of us. I don’t want class to exist! And if we did manage to live side-by-side instead of on top of one another, who the fuck knows what would happen to our sense of taste. I thought of the meme rhetoric ‘I am cringe but I am free,’ and how its sentiments might become redundant if creative expression ever became untangled from status. Maybe I should not have painted over the cringe, his cringe. But I wasn’t feeling well in my body or my head. I thought about how black holes pull things into them, irretrievably so, and white holes — which are only a theory — spit everything out, constantly, in a fast vomiting compulsion. Sometimes I feel one way but think the complete opposite and I don’t know how to make peace with that. That’s how I find myself in these situations, paint drying around my ankles, trying to keep me in place.

I think I infantilised Mr Doodle’s style — and his proclivity to emulate somebody else’s — in an attempt to knock him down a peg or two. And I still think that’s sort of fair enough. The work is childish and thin in subject and form, it’s obviously derivative, and it’s also basic in its execution. Doodling is very much about a mindlessness, and so it feels like an overextension to reward such an automatic mindlessness, even on this scale, with 4.7 million pounds in art sales and a big fuck-off house. It is like a kid being given a birthday card with more money than they know what to do with. But I say those things, and I feel them, like there is a right and wrong way to be and to be responded to, but if I was in that position… if I was the kid opening the birthday card with a hundred quid in it because someone was willing to give me a hundred quid — or if I was the artist selling doodles for a million dollars at a Tokyo auction because a buyer was willing to give me a million dollars for a simple doodle… Well, isn’t that one way to achieve liberation, even if it’s only for the self? And maybe that liberation looks like your own mansion and the right to cover it from top to bottom in absolute —

Shit. I’d forgotten all about the dog. It was dark outside. The Agency would be after me, and so would the Doodles. I couldn’t breathe for the paint fumes. I needed to get out of this room anyway. So, back on my hands and knees, I crawled towards the door in a panic. Oh god. I couldn’t remember what time this dog needed feeding, or if it had medication. I’d left it alone so long that it might have pissed all over the office or ripped up drawings and furniture out of frustration. God, why hadn’t it howled? I was sliding across the floors of the different rooms, back through the clouds, the splats, the jigsaw pieces. My head was banging but eventually I found the office: there was a doodle desk inside the Doodle House, and right next it, a doodle dog bed. It blended in with the rest of the room but I found it easily because I was so low to the ground. I started apologising out loud, and moving up slowly so that I didn’t spook the animal. It seemed fine. Sleeping. I got closer, ready to introduce myself.

The dog was white with black markings. And when I went to pet its head, I discovered the doodle dog was made of pen and paper. At least, I think it was.

For legal reasons or whatever, this is a story. Fan-fiction for the art world. If you’re here at the end of the text, please comment a dog emoji on our Instagram or share the text with the emoji on Twitter

thank you for reading!