Turner Prize 2024

ZM

I am on my own, in the Tate Britain to see Jasleen Kaur’s installation for the 2024 Turner Prize: Alter Altar. There is a long room in front of me. A long carpet, red, funky florals. It disappears into the misty distance. The room is so long it has its own horizon line. At the other end of the room, barely visible, there’s a long table with ruched lilac satin tablecloths. It is like an altar, wearing a shimmery skirt, so long, like the last supper but instead of disciples there are sculptures of enormous disembodied brown hands, wood-grained and gesturing delicately. Above me, there’s a suspended ceiling made of blue glass. The room is enormous, engulfing, an expanse that makes it all feel liminal. But the suspended ceiling is normal ceiling height and it is also a window, because the light pouring through is making the room glow baby blue.

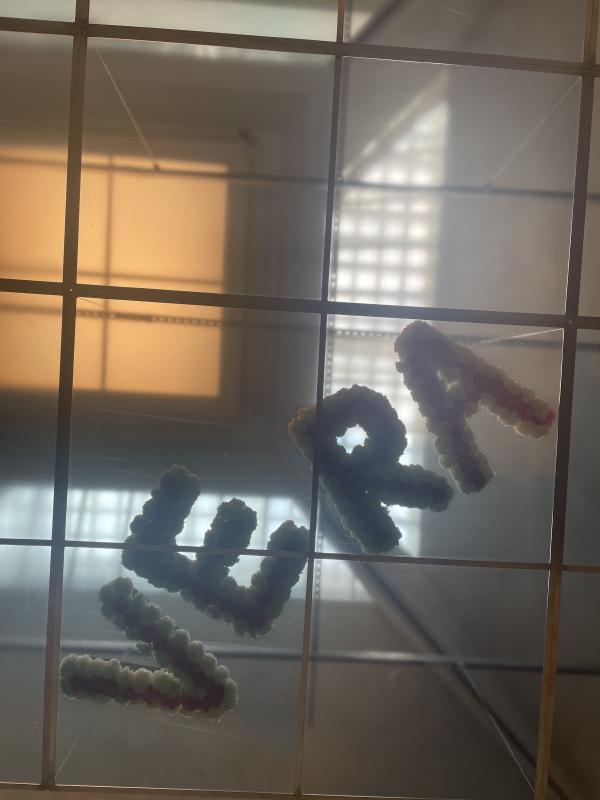

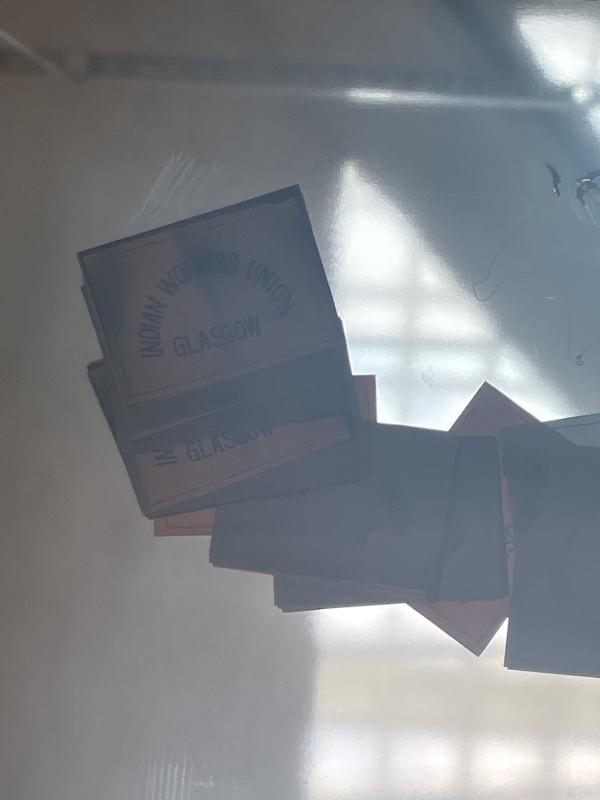

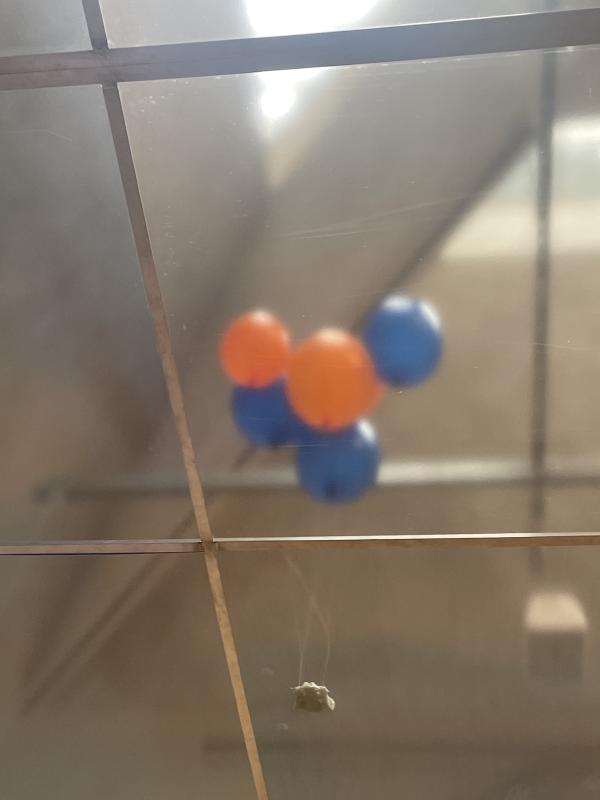

Carpet and ceiling, me in between, nothing else. I am sandwiched, stuck, in a tunnel and passing through. There is sound, a soft droning hum. Every so often something goes ping, like tiny cymbals are being clashed together, gently. I walk fowards, to the banqueting table. I look up. There are objects on top of the ceiling, and I can see them through the glass. On the other side: a bottle of Gucci Rush and a fake tongue, nearly empty 2L bottles of Irn Bru, an unmade jigsaw of Bhagat Singh, cash (Scottish £1 notes), fake vomit, casette player radio (and CDs, a Qawwali mix by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan), a very long wool scarf, fruit pastels, softmints, glow in the dark green prayer beads, flyers that read INDIAN WORKERS UNION GLASGOW, orange and blue balloons tied to a weight, a floral tribute with lilac and white flowers, spelling out the name VERA, orange tracksuit with an UNsmiley face and CAN’T DO IT lettering down the leg. I walk through, between the funky floral carpet and the blue ceiling sky. My head is tilted up the entire time.

I approach the altar and the wood-grained hands have tiny prayer cymbals perched between their fingers. Something to my left goes ping, just as I blink but I swear, I saw the hands move. Now I am at the long table, I can see the rest of the room. On the floor on my right there’s two enormous images printed on paper and laid out along the floor. One: Muslims and Sikhs praying together. The Muslims are wearing skullcaps and kneeling, the Sikhs are wearing turbans and standing behind them. Both groups are facing the camera, all bearded men wearing kurtas, their hands out in front of them. The universal oneness of God, la ilaha illallah, bhai-bhai-bhai. Two: this is an image I recognise. It was Eid in 2021, two men were removed from a tenement building in Pollokshields in Glasgow’s southside and bundled into an immigration van. People from the neighbourhood surrounded the van, blocking it in, yelling let our neighbours go. The police tried to disperse the crowd but no one budged, and they had to let the two men go. One of them, Lakhvir Singh, was an Indian national who’d been living in Scotland since 2008 — much longer than the five years required to be granted indefinite leave to remain. I recognise the image from Twitter, the news. Shot from the opposite building, police in fluoro yellow vests surround an immigration enforcement van, surrounded in turn by a crowd of masked Glaswegians.

It’s funny, isn’t it. Art is normally nailed to the wall at exactly eye level for someone of average height. This room is empty at that presumed and standardised eye level. Everything is up above me and on the floor. It cages every body in the same way, creates a kind of tunnel vision. Here I am, all alone in the Tate Britain, this bastion of British culture, home to the nation’s art in the nation’s capital. But I am also not actually in London. I am elsewhere, looking up at the Pollokshields sky. I am in British East Africa, the Colony and Protectorate of Kenya, or Gujarat, British India, Punjab’s new capital, Post-Partition Chandigarh, freshly designed by Le Corbusier. I am staring directly into the sun. The sky is a vitrine full of objects, cabinet of curiosities, you couldn’t have curation without colonialism because it is about hunting things, trapping things and displaying them like they are dead. None of these objects on the other side of the ceiling sky are dead though, they are actually alive and mid-use and they are lying around ready to be picked up — I am just on the wrong side of the glass. I am on the inside looking out at the world, where the world is full of life and objects: balloon, fake vomit, Trebor softmint, £1 note, Gucci Rush, fake tongue, Blessed Irn Bru. No, no, there is no vitrine. Only the ceiling sky and the floral carpet and this liminal space in between. There is no review, only the feeling that I am floating in this enormous middle with no sense of scale — feeling small because the room has me swimming, sublime.

I am three years old. I am wearing black polyester trousers and a baby pink crushed velvet tshirt. I have powerful baby hairs and a mini-ponytail on the top of my head, just like my idol, Groovy Chick. I am wearing silver glittery eyeliner and a pink jewelled bindi. I am in North West London, in a banqueting hall on the second floor, above a restaurant or a cash and carry, on the side of a dual carriageway or a slip road. The floors are carpeted, red, funky florals. There’s a square laminate dancefloor. The tables are large and round and they have long, thick, creamy white tablecloths. The chairs are wearing bodycon dresses made of the same fabric. They have sashes tied round their backs. There is a discoball, coloured lights sweeping across the room. All of the walls are covered in creamy curtains, ruched folds, grazing the floor. This room feels like an upholstered womb, I am an egg being incubated, I am floating and small, I am going to die of embarassment. It is my uncle’s 50th birthday and I am going to do a dance in front of everyone. No, it is my cousin’s wedding. No, it is my aunt and uncle’s 30th wedding anniversary. It’s Harrow cricket club’s yearly fundraiser. Diwali or Navratri. This isn’t a banqueting hall, it is the Navnat Centre. A man is holding a microphone, wearing a suit that fit him 20 years ago, with emourmous lapels, a grand moustache, aviator glasses. He is making a nice speech that no one is listening to. There’s an open bar. There’s a buffet with stainless steel tureens lined up across a long table. Oversized serving spoons. Everyone is eating kofta, dhal makhani, chilli paneer. It’s a dinner and dance. I drink blackberry and lemonade in a tall glass, with a straw. There is a 2L bottle of coke on every table, people are drinking from small white plastic cups, the kind that crinkle and crunch. The DJ is called DJ George of the Jungle, he’s playing Bally Jagpal and Rishi Rich, Juggy D, RDB. There is no DJ, and actually my uncle is playing the harmonium and everyone is singing bhajans from pale orange booklets with low res photocopied Baby Krishna and my aunt is at the front with a ringbinder. Disco lights, I am dancing with my cousin Nagina. She is 16 and she wears lipgloss. She put the eyeliner on me. She let me borrow her scrunchie. We are holding hands and she is swinging me round and round and you can’t hear over the music but I am screaming because I am having so much fun. I fall asleep lying on two chairs pushed together, music pounding. There is no review, only this feeling of being warm and small, falling asleep in the dark of a second floor banqueting hall overlooking the North Circular.