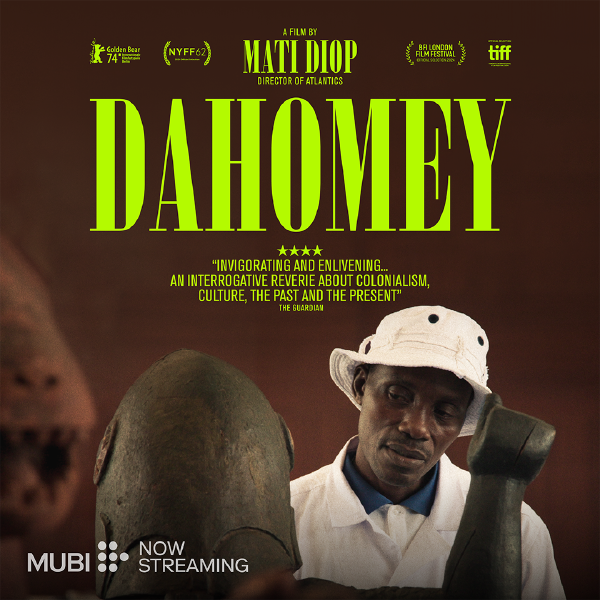

DAHOMEY (dir. Mati Diop)

ZM

The Kingdom of Dahomey was one of West Africa’s most powerful pre-colonial states, lasting from about 1600 until 1904 in present-day Benin. Over 300 years it became a regional power by expanding and conquering surrounding cities, participating in the Transatlantic Slave Trade and building precarious trading relationships with European powers. In 1890, territorial disputes with the French escalated into the First Franco-Dahomean War, which the French won, leading to the Second Franco-Dahomean War in 1892. A French Colonel called Alfred Dodds led an invasion of Dahomey’s capital, Abomey, and looted the Royal Palace. He took these stolen treasures back to France, to Paris — the metropole — donating them to the Musée d’ethnografie du Trocadero, the treasures were shifted to the Musée du quai Branly. They stayed in Paris for 130 years. Nine of the treasures were on display in the museum’s permanent exhibition, the other 17 were kept in storage. In November 2021, after more than 50 years of demands for their restitution, the haul of 26 royal treasures were returned to Benin. The 26 treasures included: anthropozoomorphic statues of Kings of Dahomey (King Ghézo, King Glélé, King Béhanzin) also known as Bocio or power figures, carved thrones, an asen (a portable iron altar), and carved palace doors. They were carefully taken out of the Parisian museum’s glass boxes, packed up into new special wooden boxes, wheeled into a cargo plane and flown out to Benin where a red carpet was waiting for them. Their departure, their journey and their arrival was documented — in a film by Mati Diop, called DAHOMEY.

The film starts shy. Tight glossy shots of the river at night, lights gleaming off the water and completely silent. The camera lingers on its way to the museum, avoiding direct eye contact until it gets to a heavy white door. A dark window at the top of the door, tightening in, plunging back into darkness. Then a voice. The beginning and end— or many voices speaking in unison across tone and texture, arcane, from some sci-fi speculative future, from some ancient past. I journeyed so long in my mind but it was so dark in this foreign place that I lost myself in my dreams, becoming one with these walls, cut off from the land of my birth. As if I was dead… There are thousands of us in this night. We all bear the same scars… They have named me 26. Not 24. Not 25. Not 30… Just 26. Something whooshes around this voice, an energy or the air around it. I can’t tell where it comes from — the universe or a spirit or a body or a vessel — I can’t tell if it is solid or immaterial, who it actually is, if it is singular or plural. But I know it is a voice that speaks for or through the 26 royal treasures. Maybe more, maybe older, maybe beyond. But for now, it is 26.

Then back to a bustling museum, technicians and object handlers wearing work gloves, masks and eye goggles. They have a crane, a winch, chains and tissue paper. They are lifting statues out of their glass display cases, very carefully wheeling them across the shiny floors, and depositing them into boxes. It is graceful, elegant, silent. It is like watching a weird ballet, bodies move and gesture and flex. No sound other than machinery and the scuffling of bodies, movement. All around the object, the object is central. They diligently document the object’s condition. They tie ribbons around them to keep tiny nails and chains in place. They are so delicately careful, gentle, even with their winch and chains cast round a statue’s neck, they have tissue paper wrapped around the chain to cushion the surface. But they treat these statues like objects, like corpses. They lie the statues down in specially made wooden boxes, coffins. It is like a balm, soothing something away. The otherworldly voice was like a knife and this is washing the sharpness off. The camera is boxed up with the objects, the lid is screwed on. Into the cargo hold, into a plane, to Cotonou, a port city on Benin’s South coast, overlooking the Atlantic. A crowd of photographers wait for the boxes to emerge from the plane. The truck they are loaded onto passes by a construction site and everyone stops to watch it go by. Women cheer, dance, clap, ring bells — it is like a parade, a wedding, a procession. Motorbikes surround the truck in a convoy, waving the Beninese flag. They arrive at the Presidential Palace and are unloaded onto a red carpet with a gun salute.

When night falls again, something magical happens. It is like that scene in Fantasia with the Waltz of the Flowers, a dream sequence where the land comes alive around the treasures. Something energetic or atmospheric in the trees and the shrubs, the flowerbeds, the shadows, the heavy silk flag rippling in the wind. The treasures are being kept in a temperature controlled room, under security cameras and the watchful eye of a guard. But then the glass door to the room opens and the net curtains blow out on the breeze of this huge gust of wind — something is escaping, something is being set free. The film could end here! This could function as an ending, a return from the wildnerness, a homecoming, full circle, narrative closure, resolution, restitution. Everything could be as it once was before, the wrong could be undone, something could be liberated.

Everything is so strange. Far removed from the country I saw in my dreams. Of course, restitution isn’t resolution, it isn’t an ending, it is just the beginning. Colonial legacies cannot be undone with a simple swap, ctrl alt Z, you cannot just put things back the way they were. It is like trauma — one thing that happens has a domino effect, complicating and mutating and happening, happening and happening and a million other little things happen too. 300 years have passed, Dahomey doesn’t exist anymore, Benin has remade itself in the absence of these treasures and it’s all different now. Not an ending, a beginning — this is an inciting incident. These treasures, these objects, how should they be received? The rest of the film is the treasures being unpacked, the museum being remade around them, the grand state opening with officials rolling up the red carpet in their fancy formal outfits. And then it cuts to a hall at the University of Abomey-Calavi, where students are gathered to debate through the perspectives on what these objects mean to them, in the present day, in the future — for the political and the social life of the country, for the people, for the culture, for France as well as Benin. That open debate is the best bit. They pull apart an attempt at understanding this moment as neat resolution or karmic justice. They question place, power, display, purpose — they are rigorous and critical. They chip away at what the 26 treasures actually are: are they objects, art, statues, are they spiritual religious objects, idols, icons, symbols, political tools, soft power gesture, geopolitical chess move — what actually are they? I don’t know, I feel like any attempt to box restitution away as an ending just unravelled, fell apart as they spoke. DAHOMEY gave us the happy ending upfront and then the film unmade itself.

The film had to be unmade, instability is the only honest option.

I remember being sat in the studio at art school, it must’ve been 2014, Duncan Cambell had been nominated for the Turner Prize for his film It For Others. I was trying to find a version of the film online, a shoddy bootleg, because I heard there was a dance sequence about Karl Marx. I didn’t find a Karl Marx dance bootleg, but I did find a full length version of the film it was riffing off — Les Statues Meurent Aussi (Statues Also Die), made in the 1950s by Alain Resnais and Chris Marker. When men die they enter into history. When statues die they enter into art. This botany of death is what we call culture. AH — we all know it, from seminars, from lectures, from the essays we are forced to read. The disembodied omnipotent narrator is inescapable. An object dies when the living gaze trained upon it disappears. AH — an object is part of a culture, part of a world. It lives as the culture and the world it is a part of lives, they are tied and they make each other. The stolen statues in Western museums are dead because the culture they were a part of is dead because the world they were a part of is dead because colonialism killed it. Now dead, they are consigned to the museum, country of death where all dead things go: dead, classified, ready to enter the history of art, paradise of form, where the most mysterious relationships are established.

The museum flattens time, flattens geography, flattens objects. We see things from Ancient Greece next to things from Renaissance Italy, Sumerian pots next to the Rosetta Stone next to little beads from the Indus Valley next to ancient carvings of horses made by Paleolithic people in a land now covered by oceans — the museum flattens it all by drawing it into glass cases right next to each other, giving it a taxonomy (whatever that is), the museum forces everything to become subject. We cannot help but see the proximity, we make it an object with our gaze and treatment, we are forced to become spectators to form, as if it had its reason for being in the pleasure it gives us and nothing more! No culture other than our own, no other world than the one we inhabit — these things become statues, become objects, become art in a world where everything is art. Forget the world they were once a part of — that is another world and it has been lost, or it is made invisible beneath the museum’s flatness.

Les Statues Meurent Aussi cycles through reasoning. Here, in the Western museum, they are corpses offered before the White God of Art. These statues are not art, they are meant to be more. They are meant to be part of an ancient otherworldly cultural cosmology that disappeared beneath a conqueror’s rifle fire. Everything is so strange. Far removed from the country I saw in my dreams. Mati Diop’s disembodied ancient sci-fi narrator speaks and something bursts. Something has come unbuckled, something was made in an absence. DAHOMEY has to come apart, unmake itself so that something else can be remade from the ruins. The statues being returned to Benin have suffered a death of purpose, the students at the University of Abomey-Calavi were re-wiring them — with new purpose, new lives, new understandings, re-training a new living gaze upon them. Of course the students didn’t agree, consensus would be too close to a Hollywood smooth happy ending. Culture isn’t smooth, culture is the making of unsmooth things, the experience of unsmoothness. Night again. 26 doesn’t exist. Within me resonates infinity. Maybe the voice remakes itself. Maybe the voice is the culture, or — no. Maybe it is something we don’t have a word for anymore, because it was lost but even unnamed it speaks with that eternal resonance. Not universe, spirit, body, vessel. Not object, statue, art, work, form, thing. It is some other word, some other entity. Whatever it is, it is waiting to be remade.

DAHOMEY is now streaming on MUBI, who have given us a link to get 30 days free – if you wana watch the film, there u go!! If you want to listen to MORE thinking about restitution and museums, we spoke to Dan Hicks & Sumaya Kassim for a bonus episode of the Whie Pube podcast – you can listen here. For full transparency: we asked MUBI if they’d like to pay us for this review and to make the podcast, and they said YES! which is great because i wanted to write about this film anyway. fingers crossed we carry this energy into 2025 woooo !