I ran away to Spain

Gabrielle de la Puente

content warning: suicidal ideation

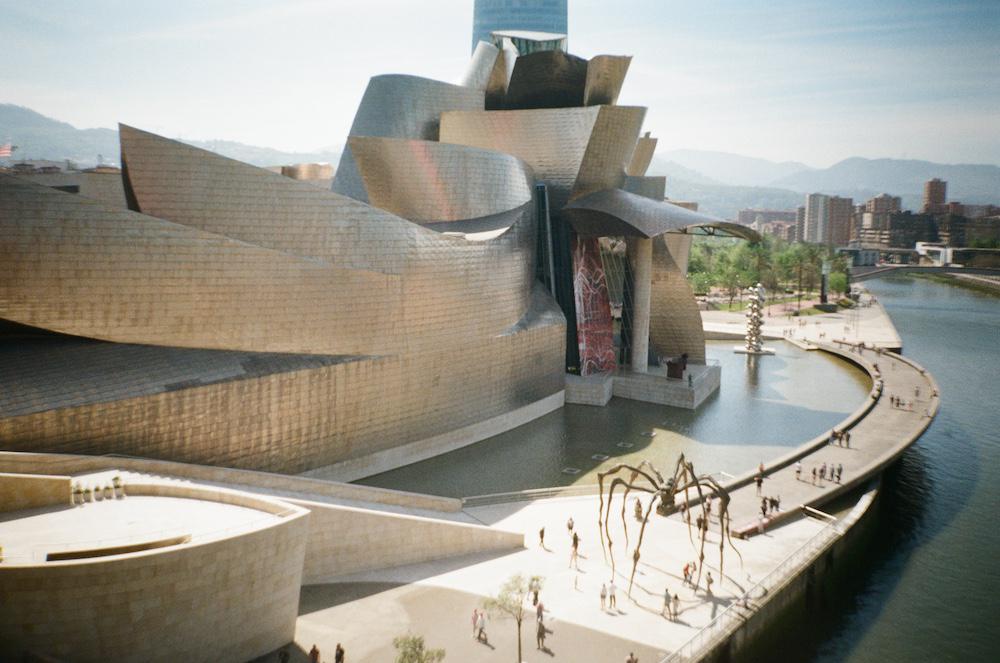

I’m sitting alone in a café upstairs in the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao on the northern coast of Spain. Very funny of me. I’m really not supposed to be here. I’m chronically ill, I speak bad Spanish, not Basque, and I should be saving every penny for a deposit on a house instead of taking myself on holiday. Not that I’m splurging. I’m staying in a £30/night capsule hotel with Russian tourists and a lone Japanese business man. The beds, which look something between bunkbeds and lockers, are like Tron-themed cryogenic chambers that deliver comatose bodies aboard spaceships in science-fiction films; I’ve never slept so well in my life. Bilbao, the coffin hotel — the whole thing is making me laugh. I’ve got that good giddiness that comes with travelling alone, or pulling off a really good surprise. I haven’t told anyone I’m coming here. No one! And that is the best part of the joke. It’s giving me the kind of giddiness that doesn’t appear and then burst, but is balanced and warm, lasting longer than it should; like tilting your head back to blow a Malteser in the air and rotating it an inch from your lips like a tiny sweet planet. Very, very funny. So funny that maybe I don’t need to own a house one day. I feel good enough right now, floating out of the spaceship and around this big tinfoil museum.

I’m happy, I’m dizzy, I’m fine. I bought the cheapest notebook from the gift shop downstairs so that I could start writing a review of the Guggenheim by hand in the café. Shaking hands. We’ve never reviewed anything in Spain before and our readers are going to want to feel what it’s like through all of these carefully chosen words. However, sat next to floor-to-ceiling windows, I’ve mostly been watching a child running through hot fountains below. She really looks like she could grow up to be me. I want to take my shoes off and stand in the water but there’s a heatwave in Bilbao, and the walk from the hotel to the museum singed my blood. I felt terrible. Arrived hours ago in a fever dream scene: there was a troupe of cosplayers outside the main entrance filming tight dance routines to a crowd of applauding tourists, and behind them, a 12 metre high sculpture of a dog covered in flowers, but nobody was clapping Jeff Koons.

I found the café. Found pintxos along the bar. Anchovies across globs of Basque-style ratatouille. This is a chronic illness exacerbated by heat; crab cakes with extra salt to recover. I knew then that I was going to have to wait in the museum until the heat died down, and that was a novel dilemma. To try being in a museum for an entire day, even as a critic. I’m normally in and out of these places because I don’t see art anymore so much as I see powerful choices being made. Which art, by whom, and from where? Who was it selected by, and for what reason? Oh and who paid, and where did they get their money from, and does anybody know why they are spending it on art? The real holiday is that it’s easier to play at being a casual museum visitor in another country where I don’t have the context to answer those questions myself. And it’s a freedom helped along by the body I have to lug everywhere; I have spent the past few hours walking through the knotted silver ribbon of this building in a bid to outlast the sun. I have seen every single piece of art on display and I have written nothing in this notebook.

Outside the windows, I can see a huge Louise Bourgeois spider poised over tourists. Fever dream continues. Behind, a river and houses blocked into full green hills. White floors reflect the sun below, and that wet Basque baby me is being picked up and dried off by its mother. I am a camera today, not a pen. I feel too ill to think. There’s only gas in the tank for looking and for laughing. Because it is funny that I am stuck in a museum, like a spider submitting to a glass, waiting to be transported and saved. Funny that, under the glass, I can’t do the job of a critic even though I’ve come all the way here — where no one knows I am. Deeply good, Malteser-spinning, to be so lifted by these absurdities that I am laughing alone in a café after the past three and a half years spent not finding anything very funny at all.

Covid scrunched my nervous system up like a paper ball, flattened it back out again, and my blood vessels lost all their fucking integrity in the process. I was left with a chronic illness called POTS and I’ve written a lot about that. What I haven’t spoken about though is how my periods were also crushed or creased or mangled in that change; how I graduated from normal, rom-com, chocolate-craving PMS to a different acronym that would never translate well into any sort of film besides maybe German Expressionism. PMDD stands for premenstrual dysphoric disorder and it it means that the day before I start bleeding, I am no longer a little bit sad but genuinely sort of suicidal. Loosely so, inactively. Physically angry, focused, hard, sharp, despairing, and stunned by just how hopeless I feel. If there was a button in front of me that meant I could instantly turn myself off, I would have pressed it by now. It would just have to be an easy way out, because I become so hopeless on those days that I couldn’t actually ever hope to act on it.

It took me a while to figure out what was going on, and it still does, because with a menstrual cycle that can sometimes take 40, 60 or 80 days to make its way around my body instead of the usual neat month, wanting to die always comes as a surprise. I worry the feeling is genuine and not anything to do with PMDD — but then I wake up the following day perfectly ready to live again, notice the blood, and the invisible drama is revealed; like blood over magic ink. I’m left with a sense that yesterday I was somebody else. There’s another sense of whiplash. PMDD is like somebody slamming on the breaks and I don’t have a seatbelt on because I don’t know I’m in a car or a metaphor, so I fly through the windscreen and play dead on the road, a poor stunt man who wasn’t expecting his body to go so far. Last year, one of those fateful car crash days, I actually booked myself a stint of private therapy. I figured I might as well spend some money even if I don’t have much to spare each month because money won’t mean anything if that big red nuclear death-button ever materialises and this thing tries to force my hand.

We were only in a museum heatwave a minute ago and now we’re logging on to Zoom therapy, but I promise we will go back to the museum eventually. I wanted the reader to feel their own whiplash here at the beginning of the text, because that’s really how it goes. And I don’t know if I should be writing about this kind of stuff when I’m applying for jobs at the moment, or when most people find it easier to pretend they are fine all the time, and they don’t think about wrapping things up. I know I could pretend too. I know that I am allowed to be private, and I am allowed to keep secrets, but I like telling the truth even more. When I write, I’m standing in that final section of airport security where travellers are asked to declare if they’re bringing anything especially interesting into the country. No one ever bothers. But every text I write has me stopping at that point, ringing the bell for someone’s attention, and tipping the contents of my suitcase over those stainless steel tables. It’s all dirty clothes and a few cheap souvenirs, but that’s autofiction I guess.

I went into therapy hoping for a way to know when my body is tricking me, so that I can rest assured that I only have to wait it out, like the sun that’s frying the world outside this museum. But I left with more than that because the woman I had selected off of an online directory did that nimble therapy-thing of identifying what a person expects from life based on how they have been raised, so that she seemed to know me better than I know myself after just one call. She raised something that might never have seemed exceptional if therapy hadn’t put my life into perspective: that I have grown up surrounded by wilful people who have always done what they wanted to do. And I mean, by hell or high-water, even if doing so wasn’t the most sensible thing they could have done. That means illegal activities here and there. Flashy presents even though I grew up in a house with a hole in the roof, and another over the kitchen, both of which were still there when I finally moved out in my early 20s. But the best example of this is that one time my Nan wanted to clean inside the kitchen cupboards two days before Christmas because people were coming round. We said we’d do it for her when we got back from Tesco and got a call in the shop that she had fallen off a ladder and broken her leg. We delivered Christmas dinner to her ward. But she wanted it done! So what did anyone else’s help have to do with it?

It was this day-to-day genetic determination that caught me out because I hadn’t realised it wasn’t normal. Not normal, but not necessarily a bad thing. A blood compulsion to be a juggernaut and do what I want even if it’s not advisable. To have total self-direction, even if being a self-employed, disabled, working class writer means I am Sisyphus on a shoddy ladder. Red, sweating, half-rabid and also sort of satisfied. I remember describing my job to her and telling her about Poor Artists, the book that we were still writing at the time. I described the premise. I said, it’s a book about how difficult it is to be an artist, but why so many people try anyway. I told her we thought about why we, as The White Pube, have continued writing even though it sort of evolutionarily makes no sense to not strive for a mortgage and a safe home and enough money to have a family, or whatever. I told her we interviewed other people in the arts to ask them the same question, and she just looked at me. Of course I had written a book about the folds in that stubborn knot. She said it made perfect sense given everything we’d spoken about and, because she knew me better than I knew myself, I was inclined to agree.

Therapy dropped a stone into the well to show how devastating chronic illness has been. Now that I understood the matrix of myself, I could see how POTS was like an insult to my body, and PMDD like being hacked. Both restrict me from doing what I want to do and being who I want to be. And that’s bad, and almost obvious. But in between sessions, I realised that at their extreme, the two conditions obscure desire entirely. At that point, I didn’t have words to explain that to someone who didn’t already intimately understand the experience of chronic fatigue. It doesn’t sound real when I type it, but: when POTS is at its most disabling, I’m not lying there wanting to get better. A lack of energy and an abundance of pain means I am not wanting anything, not even relief. I’m just lying there, ill, so worn down I’m suddenly accepting of the whole situation. It’s not because I let go of my self-worth, but because I let go of myself. I feel more like a body than a person. Someone who can witness but not participate; someone whose hands can shake around a pen sitting in a café in Spain, but who can’t think of a single thing to write.

What I did tell the therapist is that I had been struggling to pace myself. In lieu of treatment, energy management or pacing is the advice given to people with chronic fatigue. Say you have an hour of energy, you would only use 45 minutes of it. The idea is that you rest before you need to, and that way you might find the quarter of an hour you saved is longer now for having broken up the original one-shot hour of activity. It doesn’t always work, but to try you have to be careful and appropriate and disciplined. Rather than being any of those things, for three and a half years I’ve been experiencing boom and bust cycles. I use the whole hour, hit the wall, tap my foot while I recharge, before taking an inch and running a mile, again and again and again. But when I told the therapist apologetically about this terrible thing I was doing against my doctor’s orders, she asked if pacing was really in me. How could I ever play it safe when playing it safe wasn’t in my nature? I felt a pressure lifting that I hadn’t realised was there, and then she said something a doctor would never suggest: she asked if I would rather boom and bust more consciously, and even let myself enjoy it. Go into it knowing I will always push myself because an hour feels better than 45 minutes. And yeah. I can take the bust if I know I’ve had my fill, because that feels like a better deal somehow. And no, it’s not sensible or good for me, just inevitable. Ancestral.

There are going to be people reading this (and maybe they work for airport security, or the NHS) who will want the name of that therapist so they can get her struck off. I will never say. She has helped me more than doctors ever have by daring me to be myself again by hell or high-water, by crash or flare or fuck-up, and I needed that! To be asked what I want no matter the consequences, because I have never really cared for those. And I told her I wanted to travel and also to become fluent in Spanish. They’d both exhaust me but it’s not like I was going to die. I thought that, actually, I would probably live longer if I tried. I’d been paying her £50 a session so that she could help me safely exit the vehicle, but I knew I had to stop therapy so that I could spend those £50s on making other wishes come true. She understood and wished me the best and I felt excited and reckless and brave and —

god, I wish I could cut to Bilbao. Tell you I took all of her advice on board and self-actualised into my final form: sick girl speaking Spanish in Spain. But, and this is no exaggeration, I got so sick over winter that I forgot last year’s therapy ever happened. POTS hits my memory hard. Worn down, accepting, slow to react and hot to the touch like an iPhone pinging constant notifications that its battery’s health has significantly degraded — a notification I usually like to ignore so that I can boom on purpose, but couldn’t. Not until Spring let me move around again, and think, and read, and I happened to sneak a look at somebody else’s Advanced Reader Copy of the new Miranda July book, All Fours, which repaired me better than the Genius Bar ever could.

All Fours is a novel about a writer who goes on a mid-life-crisis solo road trip from California to New York. She thinks it’s going to be monumental, mindful etc. Except what actually happens is she stops in the first town she comes across, looks around a shop, gets some food. And despite the fact she is only half an hour away from the husband and child she has left behind at home, she decides that instead of driving all the way across the full-named United States of America, she is just going to secretly stay in this one place for the rest of those two, three weeks she’s told everyone she’s away for. The book is two cupped hands around your ear telling you what happens inside a good secret. And it’s very good because the writer lives a different life while she loiters. Untethered from all responsibility and context, she decides only to do what she wants; and like a wheel that has popped off its axel, she follows her own momentum, and knocks into things, and bounces off of other ones with this building spontaneous desire. It is great. It is like a story I would hear about someone in my own family — someone who does what she physically, immorally, irrationally wants, instead of politely agreeing to just always be doing the responsible, usual, heavily civil sort of things expected of a woman, a wife, and a mother.

The opposite of seeing the kid with my 1990s toddler hair and face running through the fountain outside the Guggenheim, All Fours was like reading a spoiler about who I am going to become when I’m older. Or reading it was like watching a spin-the-bottle turn land on me and quickly having to find someone to kiss. A big interruption. Like heading in one direction but suddenly turning down an alley just to see what’s down there. If the therapist had dared me to become myself again, Miranda July was doubling down. I didn’t really feel ready for it. It’s like, no one I know is really doing what they want to do in life. If work and money both evaporated tomorrow — if we all popped off our axels — I think it would take us a while to decipher our real desire and bounce with the same momentum. So greased into these routines that seem decided for us, because a lack of money stipulates where we live, how we work, where we go, who we know, and even the shit that we eat. I really like stories in which people veer off course. Cleaning the grease off their hands so they have enough traction to grab hold of life again.

I need that reminder to think about what I really (physically, immorally, irrationally) want the same way I need reminding to make a wish before I blow out the candles on a birthday cake. And what I really (physically, immorally, irrationally, possibly impossibly) want is to not be ill anymore. I want health more than language fluency or good legs for travelling, or a mansion, or a Devon Rex cat, or a successful career as a writer. I’m probably not supposed to jinx what I have wished for across my 27th, 28th and 29th birthday cakes. Secret commiserations in June, to be wished for again next month when I turn 30. But the wish is starting to leak out of me, and I want this state to change. Towards the beginning of All Fours, Miranda July writes a line of dialogue for the protagonist who is describing the difference between herself and her husband before she leaves for that trip that doesn’t happen. She writes, ‘I also don’t love getting in pools, by the way. Sunday nights! Packing for trips! Any transition. Whatever state I’m in I just want to stay in it, if that’s not too much to ask.’ She says it because her husband is the opposite, and so am I, vaguely flickering, craving variety. Or I was, or I still am, even as chronic fatigue tries to close the airspace around me. Turns music to white noise. Takes a single image of my life — the ceiling of my bedroom — and plays it on a loop behind my eyes (and also behind everybody else’s), just one maddening fixed state.

If therapy dropped a stone in the well, months later, Miranda July climbed down the well to retrieve it. In March I got an email inviting me on a residency in France, and it came from someone who didn’t know me body-first, battery degraded, to not invite me. I read the email and saw the alley I could turn down. The interruption and state change. An alley, or something brighter. Miranda July towering over my conscience, like a cooler, older, more beautiful and energetic friend handing me blunt kitchen scissors and telling me a fringe would make my face look less like a 50p coin — but kindly? So kind in fact (scissor handles turned towards me, not the blades) that I agreed. Booked my flights. I had probably always thought the same about the arrangement of my hair around my face. My Mum had figured it out first and I must eventually come to the same conclusion. But it was this private friend-to-friend word I needed to remind me it was my own hair, and I could do whatever I wanted with it. And what else did I want? Did I want France? To go there, or stay? Or to have more than that? Something like Spain? (How amazing that a book can take the place of more £50s for therapy. God, I think I was half-dead before reading and half-alive after).

It wasn’t going to be a very good idea for my body if I went… but that is why going was so fun. I slept a lot, sweat through clothes, and felt like I’d been beat up. It was illogical and good, the pain a new sign of resistance. I had a sense that yesterday I was somebody else, except this time I was making that decision instead of having the decision made for me. And by the end of that week, the premise of going back to England on the return flight I’d booked just seemed comical, like reading a book back to front. I started fidgeting. Legs rattling like they were revving up for something. Every night, I lay in my bed in the French countryside looking at maps. It was like checking the social media accounts of someone you fancy, imagining a life with them, or coming back to the same picture over and over again because it’s the best thing you could have on your phone. I kept eyeing the distance between my location and the border to Spain. It was only a three hour train from Bèziers to Barcelona. It’s two from London to Liverpool. Three from one country to another? Three. Three made me want to email last year’s therapist and tell her what I was about to do; Miranda July made me want to tell no one. Miranda July made me question if I should even be writing this text.

I saw white flamingos from the train. I saw one fantastical industrial building with solid bases and convoluted diagonal columns that looked like a doctor’s office toy dipped in concrete. I saw farmhouses further inland, and people parasailing on the water when we swung back out. The flamingos looked statuesque and totally incomplete. They made me think about this girl I used to go to school with. She wore three layers of mascara every day, and told me that she waited a while in between each layer because re-applying mascara to a dry surface built it up even higher. But she came in one morning with a completely bare face and it was more shocking than it should have been. Her eyes looked like they were caving in, as though mascara had become scaffolding to her body, and the two load-bearing walls along her eyes had folded. Now that literature has given me new language to understand the friction between me and the world, I wonder if I felt bad for her because she had locked herself into one state, and I would never risk doing something like that. I think she saw my jaw drop, and maybe other people’s did too. But she never came into school without her signature make-up again.

I had to tell the people I was staying with in France that I was going to Barcelona, because I had to ask them not to drive me to the airport. I told my boyfriend too, because he was expecting me home. I knew when I got off the train that I wasn’t going to be staying very long: there were too many people for my liking, a private room in a hostel was the same price as a hotel, every building was beautiful but the ground was filthy by the end of the day, and I quickly remembered how rude tourism was. Rude in how much a tourist expects from a place, and rude in the ways the place has to contort itself to accommodate those expectations. I had to pay a tourism tax of 7 euros a night to neutralise that rudeness, which is probably fair. I spent my time enjoying the most outdoor seating I have ever seen in a city, remembering some of the Spanish I used to know, doing a second-hand clothing crawl, stopping once at a fish bar for octopus, looking at hand-dyed yarn, and wishing I could have booked to see inside Gaudi’s mad cathedral. I was following the whim-schedule and it was already sold out. I checked the trains leaving Barcelona. I looked at flights and coaches too. I packed the low-cut top covered in flowers I’d found for 2 euros, and the skein of ultramarine wool and I woke up early the next day to get on an 8 hour coach to Bilbao.

Barcelona had been too hot and I thought if I went further north things would cool off. But in the rush of good, good whimsy, I never checked the weather, and it was only when I was watching the Spanish news at a rest stop that I heard the words for heatwave and — I didn’t even care. I was in such a good mood. I could have stayed on the coach forever. I listened to the entire audiobook for John Wyndham’s 1951 novel The Day of the Triffids while the landscape outside the bus windows rose up from flat burnt-yellow fields to Norwegian-looking forests. 8 hours was nothing. I could have gone for days.

On the walk to the capsule hotel, I passed buildings dressed in the red and white stripes of the local football team and I felt like skipping.The concierge asked if I wanted the tour in English or in Spanish, and I understood every word of the Spanish tour he gave me. I headed downhill to the river and found a Chilean Spanish tutor I could book when I finally returned to England. I also ordered a kalimotxo (equal parts red wine and coke) off a waiter who grinned when I asked for one. I hadn’t had a drink since I got sick, just felt like I finally had something to celebrate, more than I have on all those sad birthdays. My boyfriend called to ask what Barcelona was like and telling him I was actually in Bilbao kind of felt like looking at your bank account and having more money than you expected. Like the therapist, he knows me better than myself. Knows what I think about things, knows where I am, knows how I feel at all times of the day. Knows enough to clone my identity and perform the dance of Gabrielle. So, it felt like a gift to tell him something new.

I slept solidly in my capsule, locked away from the sun, and the next day I sought refuge in the museum. The museum! The silver museum. We are finally back where we began. I never told you about any of the art I saw inside the Guggenheim, because most of it didn’t register. Art I already knew, old feelings I’d processed before. I appreciated the huge Richard Serra installation that seemed an elbow away from tipping over and crushing the museum visitors, and that wasn’t fixed to the floor but balanced by its own weight and shape. But there was a better example of the same effect in a different piece upstairs in an artwork that I was still feeling when I got to my second go of the café; and was still there in my gut by the time I got home, and still there when I sat down to write this text. An Untitled piece from 1984 by the Italian artist Giovanni Anselmo, it consisted of a long row of white canvases leaning against a wall in what might have been the biggest gallery room I’ve ever been in. The canvases were slightly taller than humans, looming, and evenly spaced. Thrown over the top of each one, like a pair of shoes knotted together with their own laces and wellied over the phone cables that stretch across a street, there were two huge stones connected with a short piece of steel cable. One stone was thrown over the back and the other tipped over the front so that the canvases were weighed down and fixed and rigid and just buckling under the weight; the steel cable connecting the two rocks was visibly digging into each canvas, denting through the material and into the wood, so that every leaning canvas looked hurt.

I didn’t have words on that hot, sick day to articulate why that particular artwork was the only thing that mattered, but it all seems so obvious now. The canvas is the artist and the rocks are the real world. Made of the real world, heavy, mined in hell. The canvas is the body and the rocks are sicknesses that ground that body in one place. Police and imprison it. The canvas can change states but the rocks won’t let it. The canvas is the thing that can run away, and be proof of real imagination, and become something else, or someone else and — the rocks around its neck won’t let it. I think I knew that the blank canvas is free to do anything it wants and the cut in the wood by the thick steel cable are the consequences. It was the perfect illustration of my own stupidity, or my determination, or my family. Leaning in a diagonal against the wall, the canvas is my Nan climbing up the ladder, and the steel cable is breaking into the wood like the broken leg she once ended up with. An artwork between play and punishment. I never looked up what the artist or the curator thought of the work, because I like to create meaning too. And I didn’t need to write anything in that notebook I bought from the gift shop because I wouldn’t forget how it made me feel; all of this truth is just always inside me.

I think everyone should run away. At least once, or maybe more than that. Everyone should run away as much as they need to, and I reckon now is as good a time as any to try. Tell your loved ones you are driving across the US, and then don’t. My trip to Spain did something like displacement, or data collection. A stress test of my entire sense of self. Displacement as an experiment to see if I even wanted to return to previous levels. Displacement to see how far I could go. I had to move through the world, had to cut the steel cable and fall like a rock into the river outside the museum, fly away on the capsule hotel spaceship, dream on the 8 hour coach, ride the train over steel cable borders, change states, be therapised, be retherapised and take dares from good books, and go to a city where nobody knows me. Had to! Had to, had to. Had to do things I wouldn’t expect myself to do so that I could really see who I am, and how much of that self has been decided for me, or by me. Better than a mirror. More like an x-ray. Had to see if I like that girl. If I enjoy spending time with her. See if she is worth saving despite the POTS and the PMDD and the lack of familial wealth and the daredevil inside her and the fact she might never get better. In the giddiness of Bilbao, the answer is clearly yes.

> If you’re here at the end of the text, please comment a LADDER 🪜 emoji on our Instagram or share the text with the emoji wherever you share things

> for the film photography gang, I took these pictures on a Panasonic C-D426AF using Kodak Gold 200 ISO 35mm film

Our Patreon is on a downwards trend at the moment so if you are able to support our writing please consider signing up here and/or pre-ordering our book here