the LJMU degree show

Gabrielle de la Puente

Content warning: graphic medical procedure

About a month ago now, I was on the bus home from town with my boyfriend when somebody got on holding a long thin wooden object. My boyfriend was on his phone and didn’t notice but I had made a decision a while back that instead of looking at images of the world, I should look at the 3D unpredictable vast wild thing whenever it’s right there around me. I should feel it. Short skirt, skin on rough bus seats, real dirt. See the clothes other people wear. Hair styles, no style. I have all the time in the world to go on my phone when I’m at home. But if I look up instead of down, I remember the city. Plus, I get to see things like this. Long wooden objects I have no words for.

I thought of the miscellaneous category for decorative items on The Sims, and how that is where I learnt what miscellaneous meant although I didn’t know how to say it for years. This item looked heavy. The wood was varnished, had a bit of shape to it, and was attached to more wood at one end. The person holding it had their back to me, swaying while the bus rocked them between a metal pole and their wooden one. I summoned my boyfriend to play a guessing game with me. We decided it must be something nautical because where else do you find wood these days. Churches? Schools? The bus climbed out of the city centre, passed under the big summer trees making a room of Princes Avenue and headed south. I was happy to conclude with the boat guess but my boyfriend needed confirmation. He stood up to ask for the answer, but just as he went to, the owner got off at a stop near the cemetery. The bus moved on and we forgot about it. But I remember my boyfriend put his phone in his pocket for the rest of the journey home.

Over the following weeks, I was very ill. Nothing viral or limited or easy. It was the seasonal chronic illness changeover from spring to summer, when everybody else gets lifted by new sweet heat, and longer days make people feel like they have all the time in the world and more money in the bank — and I feel none of that because my blood vessels go boom. Post-exertional malaise, malaise without the exertion. Bad headaches, orthostatic torture. Most afternoons have been spent sleeping and I resent it. I was in France and Spain and London just over a month ago and now an anchor has been dropped onto, and right through, my bed. It’s felt a little like sea sickness how nausea has been rusting my mouth. No more buses, no games. In lieu of the 3D world, I have been lying in bed listening to the audiobook for the 1920 novel We by Yevgeny Zamyatin. The book inspired Nineteen Eighty-Four, most probably Brave New World, Kurt Vonnegut, Ayn Rand, and much dystopia over the course of the 20th Century.

I’ve been making my way through a lot of classic science-fiction this year, fingering the 90 degree metallic angle where truth and lies are welded together. It has been a kind of political education. The way the world really is, the other ways it could be, the shape we think it has to take, the many ways it almost was. The reader experience is a bit like talking to somebody who you think is telling a joke and suddenly realising they’re being deadly serious. You have to sneak your smile back in your pocket, readjust. Get appropriately serious with them. But that joke you thought was coming still lingers like a camera flash on the back of your eyes, becoming a strange memory that only you were ever aware of. Every book is a camera flash like that. A solid and temporary state, like a bear hug from somebody bigger than you. Held by rigour and secret admissions that, given how things are going, it makes most sense to be mad. Holding me, we barrel roll off of the edge of the world and, because they’re on the outside, I rest knowing the author will take the brunt off the force whenever we eventually land.

Zamyatin’s book We wasn’t published in his native Russia until 60 years after it was written. He had to seek publication elsewhere because it was a story that criticised totalitarianism. The people who live in his fictional One State do not have names, they are called only by their number. Buildings are made of glass, sex is scheduled, everyone wears a uniform, and recreation involves marching outside in lines. The numbers live in a walled city, cut off from the rest of the wild planet Earth around them. They are made to believe they are happy because their freedom has been taken away from them; they are made to believe that freedom and happiness cannot co-exist. The characters speak about the old world’s fables, how ‘those two in paradise stood before a choice: happiness without freedom or freedom without happiness; a third choice wasn’t given.’ Adam and Eve chose freedom and were cursed with misery and sin. The numbers think the opposite is worth it for their steady, needs-fulfilled, auto-pilot happiness. So effectively neutered by the way their lives have been organised, the people of the One State don’t feel the need to tell jokes. They never so much as dream.

I listened to the book inside the imaginary bear hug. It was a cold hug somehow. I tried to drink water but felt too sick. Everything repelled off of me, including the day and I slept. I woke from a deep afternoon dream in which I had been giving my Nan glasses that I had designed especially for her. She died just over a year ago, but here she was in my dreams trying on gold-rimmed glasses right in front of me. And it was strange in a way that was normal. The lenses were huge and there were far more than two of them. There were many, each with a thin slot in the back in case my Nan ever wanted to drop her favourite pictures into them. She could have the 6x4 prints facing outwards for decoration or facing in, close to her eyes, for private contemplation. What I had made for her was essentially a photo album she could wear around her face. Her own analogue virtual reality. I persuaded myself to drink some water anyway, even though I didn’t want to, and thought about the memory where this came from.

When I was visiting my Nan in hospital in the last few months of her life, I asked her if she wanted me to get the real photo albums out of the attic. She was on a shared ward with a small TV screen mounted on the ceiling at such an angle that made it difficult to see. I thought it might be nice to look at relatives, parties, holidays. All the babies, all the christenings, all the joy. But she was sick, anchored. She could hardly talk and she was obviously depressed. My Nan was a matriarch who lived to be surrounded by family and now she was spending most of the day alone while we had to abide by set visiting hours. When I asked about the albums, she managed a very quiet yes to my face. I was glad to have a mission. But when my uncle visited the next day, my Nan asked him to make sure it didn’t happen. He called to tell me and I remember the conversation very clearly because it sounded like he was gloating, like I was so far off the mark with her care, and like I’d almost done something terrible but he’d gotten there in time to save the day. I felt bad. She was really struggling to speak during that time and it must have taken so much energy to stop me. Yet, in that sickly afternoon dream I had between the dystopian chapters of a dreamless world, I was still convinced she should put on the glasses and look.

The main character in We is a mathematician called D-503 who starts questioning why his life is the way it is. A few other people start wondering too, and there’s a burgeoning, infectious excitement to stand on tip toes and look over the wall that encloses their highly designed reality. The wonder does not last long. The dictator’s response is to order lobotomies for everybody in an aim to subdue the part of the brain responsible for imagination. Come the end of the book, D-503 finds his curiosity so terrifying and unnatural that he voluntarily walks into the doctor’s office and lets it happen to him too. Opting for empty happiness over freedom, he accepts a small, walled life over a full one. Between the book, the dream, and the state I was in, I felt punished. Wanted to wrestle out of the book’s hold and out of exhaustion, because I didn’t want to spend another summer living a small, walled life in this bedroom. A bad mathematician, I couldn’t square the space between the book and myself just then. Nor could I the following week, when my health got worse and I had to cancel a long-awaited trip to a book fair in Norway. I watched the plane take off without me in calendar notifications. I should schedule annual frustration instead.

I let my phone run out of battery. If I couldn’t see the real people on the bus then I didn’t want the timeline stand-ins either. Didn’t listen to anything, didn’t watch shit either. More time passed, and now I’m here, and I think this is how I felt about the book while I have the lucidity: I have a disability that means I feel worse the more that I do, the more I think, the more I move, and I was reading a book about a dystopian government that clamps down the more people do, the more they think, the more they move. I was understanding myself as living according to a totalitarian nervous system. I was hearing about weaponised lobotomies as a way to control a body. I was thinking that in this sickness there are moments when I already feel lobotomised. Subdued. Bad circulation means there is less blood in brain than there should be, so I’m slower to think and write these texts and remember things. My brain dries up like an orange peel in the sun. I want to lean into Zamyatin and whisper in his ear that I might have walked into the doctor’s office behind D-503. I think it would be fair enough of me, as I think it was fair when my Nan didn’t want to see the photo albums. I get it now.

It’s a new week and I have a doctor’s appointment in the city centre on a Tuesday afternoon. I can’t believe I have to go outside feeling this bad but I need surgery on my arm. The presenters on the radio station in the waiting room are discussing the general election that has just been called and while I’m sitting there I get a text from someone I haven’t spoken to in 17 years. They’re asking if they can join my 30th birthday celebrations. I don’t reply. I still haven’t. I won’t. What they don’t know is I don’t have anything planned. My birthday is in June so I’ll still be burnt. I am reeling when the doctor calls my name because I’m seasick again on dry land, I want Labour to win but I don’t want to help them, and also, I thought I’d blocked my Dad’s number years ago.

I met up with my boyfriend after I’d been with the doctor for half an hour. I’d been on a bed. The doctor had asked me to place a hand behind my head and the room was utterly silent which meant that when she began snipping the insides of my entangled arm off of the contraceptive implant, I could hear each horror movie sound effect centimetres from my ear. It was gnarly. I left tense, as though every nerve ending had been pinched into a spike. If anyone were to touch me, I thought I would ring out like a tuning fork. I wonder now which is worse: the sound of a body being undone (freedom without happiness) or Rishi Sunak threatening mandatory military service on the radio (his version of happiness without freedom). There should have been a third option and it should have been the doctor inviting me to put headphones in. I could have blasted white noise or just more science-fiction. I could have called my Dad and told him to fuck off.

My boyfriend said we should go straight home, and he was right, technically. I was going to take a big hit from venturing outside that day. But I didn’t want to. I was full of adrenaline from all of the above, and the adrenaline meant I could feel my brain inside my head again. I knew that the degree show at Liverpool John Moores University was closing that week. Real summer numbers still hadn’t kicked in so I also knew that it might be my last chance to see art in person for the time being. And I like degree shows. It’s a ticket to a hundred decisions. Artists can make anything they want to and I enjoy seeing what comes out of anything. It’s the imagination the fictional One state wants to cauterise; it’s the real shrinking of arts, music and humanities courses across UK universities. Degree shows tell jokes. They dream. Last chance, might as well. We got in a black cab to save me the hill. The right, safe, healthy, technical way to live with chronic fatigue is always so obvious. When I go the other route, I feel more like an author and less like a reader. My legs were shaking in the lift up to the art studios. But if I am driftwood, at least I’ve chosen to get in the water myself.

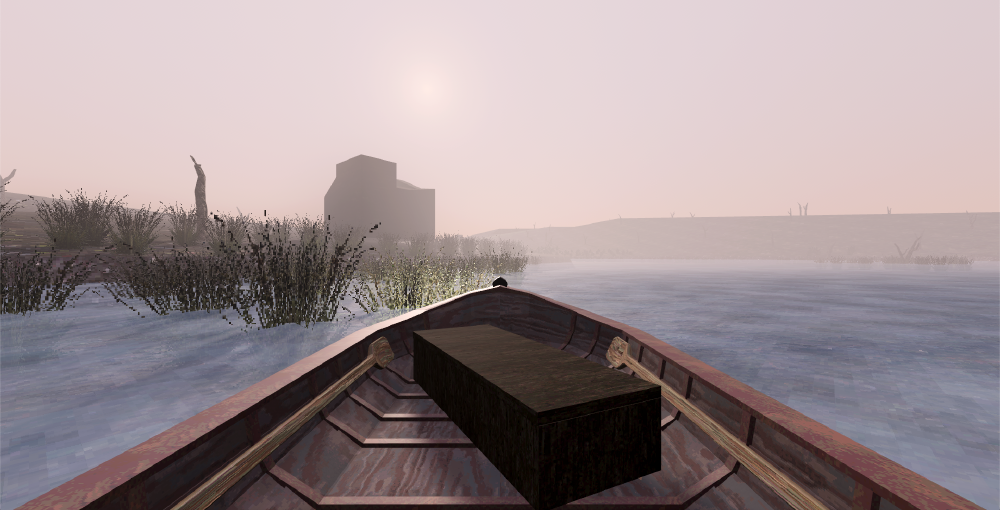

I remember symmetrical paintings by Katie Sadler that gave the impression of barbed wire, living vines or tattoos in the tribal Y2K category. Painted soft and then sharp as if with a spray gun, I decided they were sci-fi too. I had to sit down for a while in front of a piece by Lily Scott-Turner. There was a projection. Words coming in and out, body coming in and out too, crafted angel wings and a huge bird’s nest out-out on the floor in front of them. I could have climbed in there to rest but my boyfriend called me over. He was asking if I had seen the boat. The boat? He brought me to a small enclosed space that I had completely missed. Tucked around the back, there was a narrow room with a projection at one end displaying a video game. The game’s point of view showed somebody looking out over the hull of a small motorboat on misty, swampy water. Instead of a bench facing the screen head on in a typical exhibition format, there were two benches perpendicular to the game, so that the two of us sat down facing each other as we might if we were sitting in a real boat. And the simulation really worked because, between the two of us and set parallel with the floor, there was a long thin wooden object. A heavy object, varnished, attached to more wood at one end —

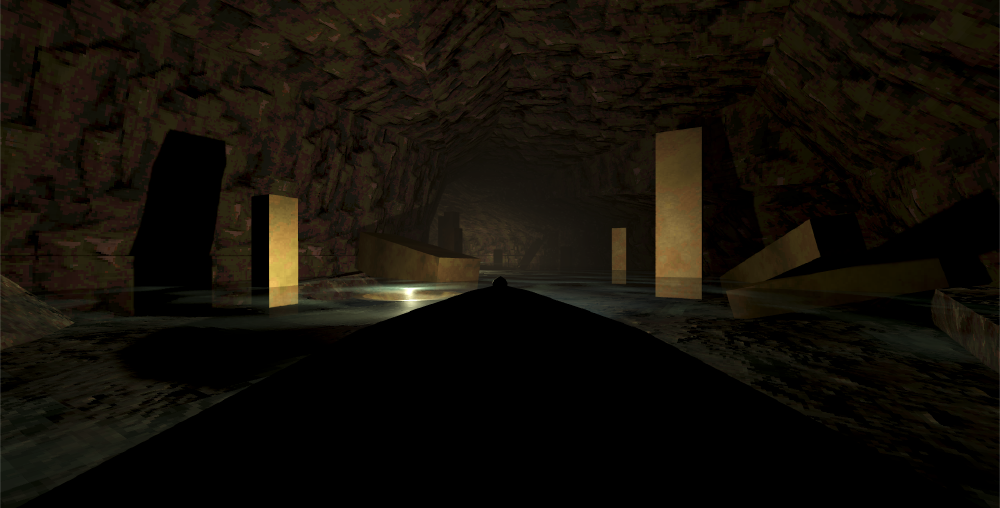

It was the thing! The mystery item we never figured out on that bus ride a month ago! It was a boat tiller. A tiller that had since been rigged up so that it acted as a very sensitive controller allowing the exhibition visitor to drive the boat in the game. We gasped. I was pretty ecstatic. Decided it was a reward from the universe — the earlier mystery solved, loose fiction transformed into something I could hold. Programmed, designed and written by Ada Null, with modded controller and sound design by Alex Brettell, we played ‘our boat, The Thread’ together from start to finish, taking turns to steer and, at one point, trying to steer together. The boat chugged over lakes, through a half-sunken church, into dark sewers and glowing caves. At one point, the player had to keep the boat straight across a tense waterfall bridge that stretched across blank space with no boundaries. We arrived into a starry globe where a translucent ghost standing next to a bonfire was waiting on the shores to meet us. I got completely pulled into the whole thing. I couldn’t really believe that this was in a BA degree show.

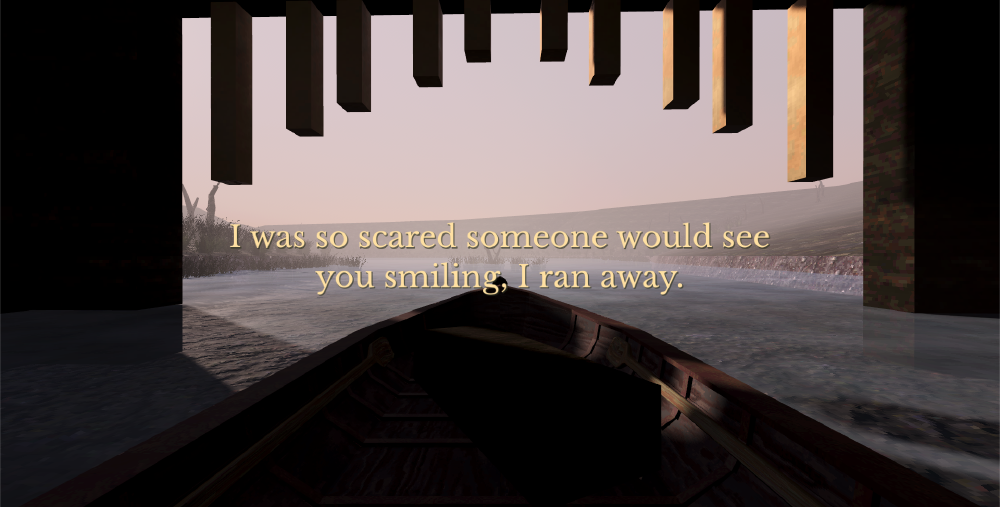

When the game ended, I thought I knew what happened. Brief, poetic text had glinted on the screen rhythmically like sunlight on water and implied we were crossing into the afterlife; that this was a love story; that the person in the boat would be meeting the lover that had died before them; that their lover was someone who had ‘replaced superstition with certainty’ and emancipated the living from all the bleary fiction surrounding death. If the Greek myth of Charon describes a ferryman that takes new souls into the underworld, then in this story, the people ferry themselves. Good for them, I thought. But I was delirious and still thinking about queuing for a lobotomy. I steer my own boat with cupped hands! I didn’t really know if it was good for them, or good according to the story, or if the game had tried to hem me into any single answer — any certainty. I couldn’t imagine choosing certainty over superstition when to do so feels like severance over an intact brain, walls over a full world, singular manufactured truth over endless possibility — over one hundred decisions in a degree show, and jokes and dreams and art. So when I arrived on the shore with the ghost and new text on screen read BONFIRE ENDING I was relieved to know there were other endings I’d missed.

I felt good. I also felt bad. It was time to go home. Later, I found the email for the designer and asked if I could get a build of the game so that I could play those other branches. Ada replied with the file and told me there were two other endings with hints about how to reach them. I opened the file on my computer as the title screen invited me to sit to one side so that I could row my mouse. I liked that, I clicked around — and then I got very sick again. I’m back in bed. In and out of sleep. I’m listening to Octavia Butler this time, and I have a new mystery to entertain me, not in the purpose of a long wooden object but in the secret paths through a video game when I’m next ready to play.

— please comment a boat emoji on our Instagram page, or share this text with a boat emoji wherever you share things. We do not check our analytics anymore so it’s a nice way to know readers have passed through 🚤

— ‘our boat, The Thread’ is available to play HERE