The Unbearable Lightness of Forgetting My Name, Noorain Inam

ZM

I am on the bottom deck of the bus and my eyes are closed. I can feel the sun blasting through the window, I can see — I can see the backs of my eyelids. I have a powerful mind’s eye. I can close my eyes and retreat into the interior landscape of my head. It is like An Other Space. A world that is secret and private and just as real as the outside world, just as expansive. My eyes are closed and I can see the backs of my eyelids. I breathe in through my nose. I am trying to remember a painting.

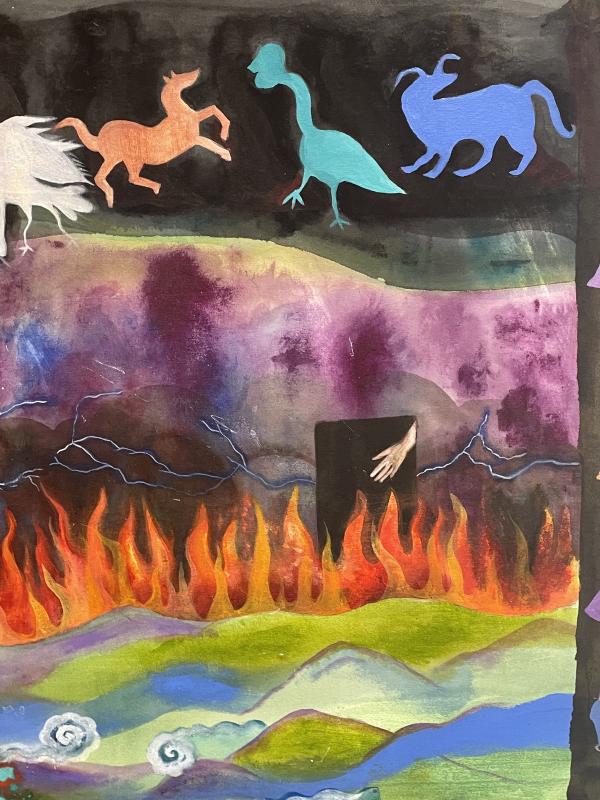

A black sky, misted grey in patches. A wide landscape. The land is purple and hazy, stretching out on a rolling curve. It cups the edge of a bay, waves tumbling over each other in green and blue. It is colour on colour, colours laid flat against each other, blotchy like tie die where they splurge and bleed out. This is the frame, the square base of a painting: The unbearable lightness of forgetting my name by Noorain Inam. It’s pretty big. As I stand in front of it, the painting fills my peripheral vision. It doesn’t end. I reckon I could stretch my body across it from corner to corner, be encompassed by the image. The sky and the land are zoomed out and distant, like we are looking at a cross section of the landscape from afar, like a pinched window, clipped out of a wider scene. The waves break into fire, orange and yellow flames lick their way across the shore in a radiant line. Clouds curl over the waves and in the sky, zigzagged with lightning. A yellow sun peeks through like a mystic orb. Stars twinkle in the black sky, little gems in blue, orange, purple with white halos, they look like they are falling out of a cloud. Below them, a line of animals, creatures, beasts? A crane or a swan, a turtle, a peacock with a blue human head and a horse’s tail, a peacock’s head wearing a long purple skirt, peacock peacock, person, man, peacock, person, pony. A prancing pony. They are marching over the land, uphill in single file. None of the animals have eyes, their heads are flat colour, sometimes their bodies too. The stars are falling on their blank heads and there is something overwhelmingly sad about this painting! Under the animals, under a black murky paint layer, I can see a ghost of an outline — a line of women with flames on their heads, haunting the shape of the animals covering them. I don’t know what happened, where they disappeared to or why they transformed. But they’ve disappeared.

The Unbearable Lightness feels like a fitting reference (to that Milan Kundera novel, The Unbearable Lightness of Being). The painting feels like a magical window into An Other Space, where everything is distant and fleeting, light touch, strange and — it’s a strangeness that can only be existential, metaphorical or allegorical. It is chewing up the world looking for something. Generally, existentialism always flips back on itself, from the outside in. It’s an extreme interior sport. Landscape, the sublime too, it always shrinks down to a human scale eventually because — well it’s chewing. The human body reasserts itself in pieces. In a vignette at the base of the painting: the soles of two feet, reclining and bare. On the left, Cardinal East: a black window with a hand, outstretched into the void, fingers splayed. Above the sun: a hand extended in blessing, reaching to touch. An ear, cut out and cartooned over a wooden window. The women reappear, as a border around the sides and bottom, cupping or containing the image. They are hazy, but more detailed than the animals. They are standing, seated, dancing, all wearing embroidered dresses, long skirts, veils or belts. They are like angels, or sprites, celestial and otherworldly, removed from the action and at a distance on their border.

It’s important for me to specify that my eyes are closed. I’m in my interior mental landscape and mind’s eye. If my eyes were open, I’d be on the bottom deck of the bus or contending with the painting in the real world. I’d have to talk about the way the painting functions in and against the real world. I’d say that Noorain trained as a miniature painter, so the flatness functions in proximity to a subcontinental art historical canon. I’d say linear perspective was a European invention and I’d inch towards a reasoning that could prop that sweeping statement up from behind. Maybe something about the painterly conceit of two dimentional space contorting itself away from flatness. I’d say Leonora Carrington, de Chirico, Surrealists, Symbolists, metaphysical painting — trace a line all the way back to Medieval Italy because that is where that comes from. It’d be a good fit because the angel sprites along the border remind me of the predellas on Renaissance altarpieces, always home to miniature scenes of a saint in real life (on a horse, interacting with a monk, blessings and miracles). It’s important for this review to take place in a setting that is mostly imaginary because I want to be able to suspend a bit of disbelief. I want to make the painting float. I want to gently unfasten it from the wall and vanish the space around it so I am actually talking about the image alone, isolated, in a vacuum, contextless. There, floating in imaginary space, a different set of contexts and connections open up. They’re within me, my mind’s eye, I can commune with the painting in a weirder way.

I once had a painting tutor who said every painting is either a window or a mirror. I remember laughing at it as a very trite aphorism, powerful simplification, reduction to a fake binary. But — what if it wasn’t trite, what if this is a very astute point? What if there are two ways to catgeorise images? Outside/inside. Paintings look out/paintings look in. Paintings reveal/paintings reflect. Transparent surface/opaque surface. I guess it all hinges on the premise that a painting is a kind of limit: a point where image bounces back at you, a boundary between two distinct image spaces. That doesn’t feel true to me. I think paintings can be portals, screens, voids, tunnels, lenses, pockets, pedestals, trapdoors, fishbowls, seeds.

Paintings are everything because they are Other Spaces, negatively defined. They’re just whatever this space isn’t, they’re Over There and away from us and — maybe that’s why they feel like a limit? Because by being Other Spaces Over There, they’re at a distance and different and the space between us and the painting feels like a huge yawning gap, this space ends and the painting begins and so that feels like a limit — doesn’t it? Yeah, sure. But what if it flips back on itself, from the outside in? What if the painting pierces something inside you?

(What if the mirror-window-portal-tunnel-trapdoor-fishbowl speaks to the interior landscape of your mind’s eye, what if it is a dream, what if it’s your eyes shut and looking at the backs of your eyelids and that’s the limit? Not to sound woowoo but maybe paintings are just feelings, instincts, dreams, fiction — images, what if image the smallest definition you can crunch it down into, no further, an image isn’t a soluble thing.)

When you imagine something in your mind’s eye, what does it look like? How much do you see? If you imagine a person sitting down on a chair, what does that look like? Do they have long or short hair? What does the back of the chair look like before their body obscures it? What is around them in the room, and where’s the nearest window? My mind’s eye is powerful, it renders these images in snippets. Their hair is long, black, straight. The chair’s back is cushioned and upholstered with a scratchy grey cloth. It’s next to a table and a bookshelf and the window is actually a big glass door. I imagine these things individually and powerfully, but only when prompted. Snippets, you see? The mind’s eye has got a wider peripheral margin, tunnel vision.

There is something uncanny or overwhelming about Noorain’s painting because everything is small, detailed and rendered with perfect clarity. It is a collection of snippets, imagined and conjured all at the same time. There is no margin, no periphery, no concentrated centre for focus to land. It is so big and so small, it is so flat and wide. The colours are dark, like jewels, emerald green, amethyst purple, sapphire blue and with these dazzling flashes of ruby red punctuating like little stab wounds. It pierces something within me, picks a scab and I don’t know where I’m bleeding but I feel the contact. Like that, it makes me want to collapse the distance between the world, my body and the interior landscape, crumple the void within me. It makes me want to reassert my human body. Place myself: feet at the base of the painting in the vignette, left hand to black window, Cardinal East, right hand in the void, fingers splayed. I would gently rest my ear against the wooden window and stretch my body across from corner to corner, encompassed by the image.