Imran Perretta @ Somerset House Studios

ZM

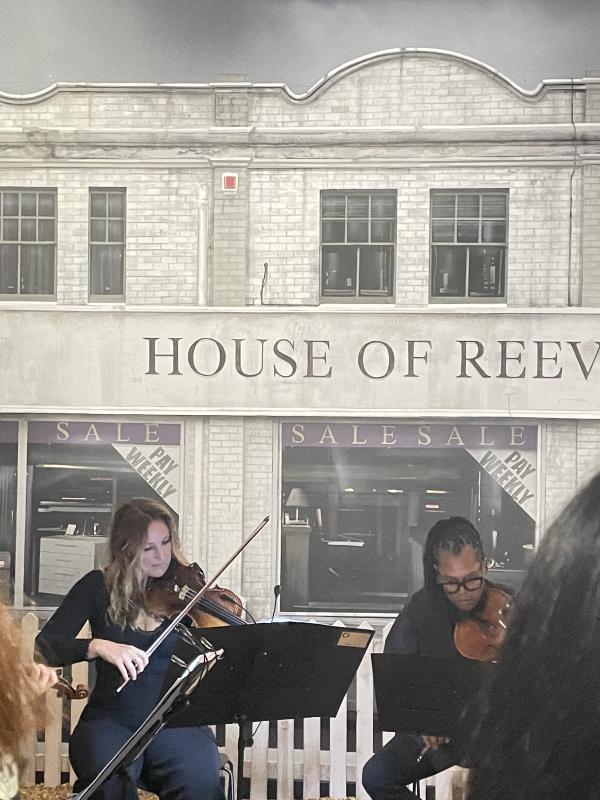

I am in the Lancaster Rooms at Somerset House Studios. Right at the back, the gallery pressed up against the river, my back pressed against the wall. In front of me there is stone floor that turns to gravel. There are weeds planted under the stones, a lucozade bottle cap, bits of plastic, zipties, NOS cartridges like little metal bullets, bic lighters, scraps of cardboard, crisp packets— a whole archeological site, crud that accumulates at a city’s outer edge. Two benches and two planters, withered trees dying up against the ceiling. There’s a painted backdrop setting the scene: a furniture shop called HOUSE OF REEVES. The building is large and white, furniture is stacked in the dark window.

Here I am, in the middle of a dramatic set, a diorama. A replica of Reeves Corner in Croydon, an intersection between an A-Road and Croydon’s Old Town, named after the furniture shop that’s been on that corner since 1867. The bit where the gravel is, the bit where I’m standing used to be another building that was part of the shop. In August 2011 the Metropolitan police murdered Mark Duggan, an unarmed Black man, in broad daylight on Ferry Lane in Tottenham Hale. It started there in Tottenham, a part of London that has a long history with the Met. A teenage girl was swarmed by police with sheilds and batons, a police car caught fire. It started and then spread up the High Road, West Green Road towards Wood Green, over to Enfield, Brixton, Peckham, Lewisham, Hackney, Walthamstow, Stratford, Woolwich, Bromley, out of London to Birmingham, Manchester, Wolverhampton, Liverpool. The streets were on fire. The Met sent out the riot squad, mounted police. They don’t read the riot act anymore but it begins: OUR SOVERIGN LORD THE KING — fuck their King — His Majesty King Mob. One whole year of tory austerity, it got so much worse. Buses were burning on the High Road, I could hear the helicopters, they smashed in the windows of the bookies, they lied about what happened to Mark Duggan, they lied.

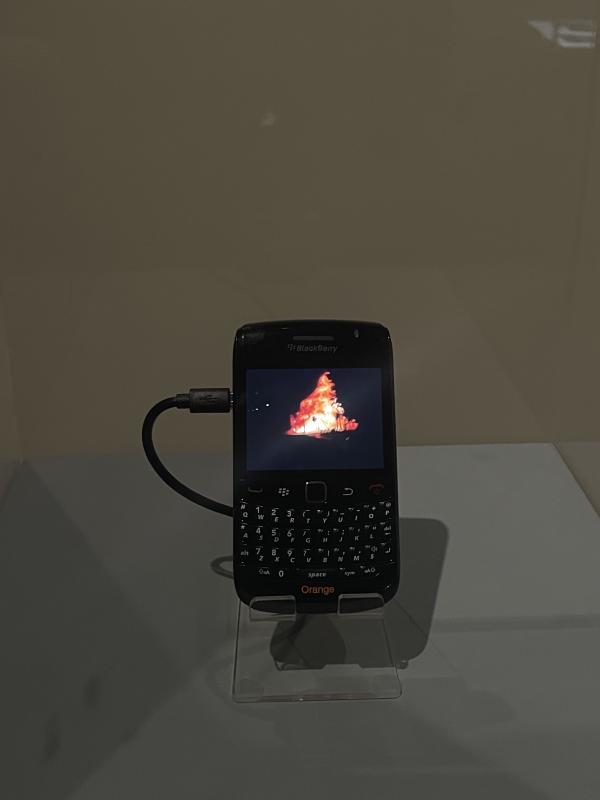

In Croydon, the House of Reeves (on the North side of the corner) burned down. The firefighters arrived too late because the police said it wasn’t safe. Here in the gallery, behind the backdrop, there’s a glass case with a Blackberry propped up. It’s playing a video of the flames licking the building, towering, enormous. It’s amazing, a solid block of fire. We’re standing in what remained, where the flames were, facing the building on the South side. Now it is gravel, planters, suburban liminal space waiting for regeneration, property developers, construction, something. The scene is One of the Three Acts that make up Imran Perretta’s A Riot in Three Acts. The video playing on the Blackberry is another Act.

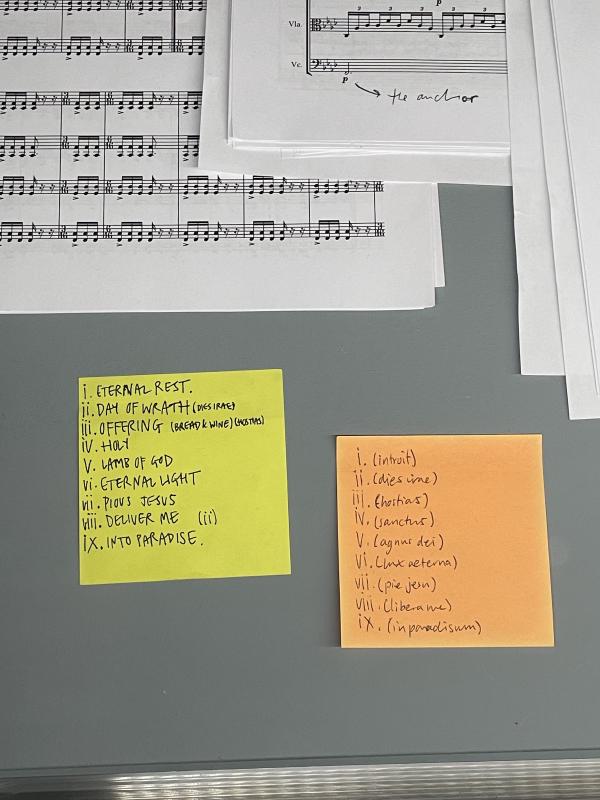

The Third Act is spread out through the room, gathered on the gravel in front of me. A string quartet, Manchester Camerata, are playing A Requiem for the Dispossessed. I am quiet, reverent before them. I know that Imran composed the music, William Newell arranged the score. I know that the whole thing makes up a dramatic scene, cinematic manipulation, affective tonality, the idea that film is a form that can lead you down emotional rabbit holes. I know that a requiem is sacred music, Mass for the souls of the dead. I know that I wanted to write this text dispassionately, wih a kind of forensic or clinical coldness. I know that I didn’t want to admit to my body, take on the role of disembodied ghost, avoid the use of that selfish I. I know that I actually didn’t even want to write this text at all. But here I am, at the edge of the gravel. I know that if I blink, a lonely tear will roll down my cheek, luxurious grief, Our Lady of Sorrows. I know that Imran Perretta’s work always makes me cry.

xxx

In the Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels begin with the words, a spectre is haunting Europe — the spectre of communism. In Spectres of Marx, Derrida writes that the spirit of Marx is even more relevant after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the death of communism/capitalism’s triumph. Communism’s spectre returns to us here, in the land of the living, well after its supposed death. Derrida quotes Hamlet, a play where a ghost pulls the trigger on the inciting incident, reveals information that acts as a turning point. Not present, but a presence. The dead act in our realm, returning, repeating. A ghost isn’t quite a simulacrum. That would be a representational image, a proxy, present as copy. A ghost is something trapped between itself, between being and the simulacrum. A ghost is the limbo, it is something that isn’t. There is no such thing as linear history or linear time, the present is continually haunted by the ghost of the past and the unfulfilled promise of the future — hauntology. To have presence without being present, to be without being, stuck between states and also, right here in the land of the living.

In Ghosts of My Life, Mark Fisher writes about hauntology too. When capitalism is the only conceivable system, singular and total, society and culture stagnates. Nothing new is created because the future has failed, it is the same as the present and the same as the past. The future doesn’t really actually exist, capitalism has us stranded — stuck between states of crisis. The future is lost, its remnants come back to the land of the living, haunting us with its unfulfilled promise. Nothing new is created, culture recycles itself, constantly looking back to the past, the past constantly haunting the present.

Back to Spectres of Marx. Derrida writes that mourning makes the remains of the dead present. Derrida calls it ontologising, but I don’t really know what that means — I’ll assume it means that mourning, lamentation, is an action of summoning back into the land of the living.

xxx

I think cities are sounds. Smells and places and people and things, all of that too. But cities are characterised by their sound. Trains screeching through tunnels, traffic clunking, endless construction and people and things. There is not a single quiet room in Greater London, I know. Cities have distinct sounds, they incubate the sound, press it hard and compact, leaking it until it’s music. Detroit and techno, Chicago and house, London and —- Detroit techno, a genre coming together in the 1980s when the city was experiencing the collapse of the motor industry. Cities characterise their sounds with their own specific character. The sheer scale of the noise. A city lends itself to music, mechanisation, rapid thoughtless movement.

Not to be dramatic, excuse me, forgive me. My city is dying, or dead already. I have known this for some time. I grieve it already. The city is dead the city is lost the city is burning the city is a corpse and we live within it. I loved it so much. London is a city where the future is lost. Maybe, stuck between crises, artists cannot imagine, conceive of or create a vision of the future. Instead they go back, the past feels like a richer or more plausible territory. A requiem is ancient music. It’s ceremonial mourning, for the repose of the dead – calling them forth into restfulness.

xxx

I know I don’t want to say the word riot. In an interview with Flash Art about her film, Broken Windows, Hannah Black said, a riot is figured as a kind of frivolous or excessive or histrionic or purely acquisitive act, as if it were a high femme activity. The word is applied selectively, depending on who is acting. It’s very hard to turn a riot into politics because it is something firmly rooted in action, beyond language. Art is also beyond language. Not a form of language, or a different language, a language by any other name — art and action begin where language ends.

Politics is communicative, riots are expressive. Politics relies on someone hearing, receiving. Riots do not ask for an answer, they are the response. Politics encompasses the legible (or maybe the legible becomes politics). We elect MPs who enact the will of the people, they represent us and our interests because we cannot be trusted to manage our own interests — MPs make our interests legible, they make them politics. Demonstrations, protests, placards, chants on the street: what do we want? [insert legible demand here]. Political action: letter writing campaigns, pressure groups, lobbying. All of these things are encompassed by the political realm because they sit within the realm of langauge, so they are legible in relation to power. We have no other course of action, we are forced to make our will into language. Language, legible, politics.

A riot defies becoming language. It remains illegible, pure action. The lack of legibility gets characterised as frivolous, excessive, histrionic — irrational. But it is a kind of mourning. Something in the city has died, its music its character, maybe the soul of the city itself. If I thought about the hauntological, I would say: the city is haunted by the spectre of its lost future. The city died in 2008, 2011, again and again and again. The country died! But I don’t love the country! This ghastly island, the farce of a nation state that is only a dying empire, civilisation, the West. But my city was real. I know, because it had a sound, it had music. Now the only music is sacred, ancient, meant to transport a soul, from one life to the next — out of liminal limbo and into a proper state of rest.

Looking out from the North side of Reeves Corner. Here, on this film set replica of a liminal space, empty except for suburban crud. The string quartet are playing sacred music, Mass for the souls of the dead. The Requiem for the Dispossessed is a lament for a dead city. London is dead because the will of property supercedes the need for space, gravel sits waiting for property devlopers, a scar. I am on the edge of it, where the stone floor turns to gravel, looking out at the South corner and the House of Reeves. The strings are directing the sound right at my head. I am in this rotting corpse. On the edge and in the middle of it. Audience and actor. Our Lady of Sorrows, with 32 swords piercing her heart, one for each London borough. She blinks. A single, lonely tear rolls down her cheek and then stops. Cinematic, luxurious.

A Riot in Three Acts is on at Somerset House Studios until 10th November, info here