Unreal Estate

ZM

I am standing in front of a floor to ceiling window that overlooks a marshland. It takes up an entire wall in this flat. All the flats in this newbuild tower have floor to ceiling windows. They all have built in dishwashers washing machines and dryers. They all have balconies and underfloor heating, rainfall showers and marble countertops. But I am on the eleventh floor facing South. In the lift up, the estate agent told me that eleven is his lucky number because it is an angel number. Whenever it’s 11:11, he makes a wish and the angels do their angel magic so the wish comes true. I smiled, said I was the luckiest girl in the world, but my luck always runs out when I try and put it into numbers. He smiled without showing me his teeth. Now I am staring out of these floor to ceiling windows, looking out at the marsh and the estate agent is waiting in the hallway outside so I can have some privacy while I discuss everything with my husband.

I don’t have a husband. I am on the phone with a man I met on Spareroom, about another flat entirely. He is asking me invasive questions. How often do I work from home, how often I am likely to be out in the evening? Do I often come home late at night? Do I have a heavy manner of walking through a room? Do I snore? Does my boyfriend snore? Because the walls in his flat are paper thin — very important to note because he is a light sleeper. The Man From Spareroom can ask me these questions because there’s a lot of interest in his flat, even though his flat doesn’t have floor to ceiling windows. He has a lot of power in our interaction, which is what I imagine having a husband is like (I have never had a husband, I have never lived with someone’s husband, not even my own mother’s — in this way, I am able to maintain this ungenerous belief).

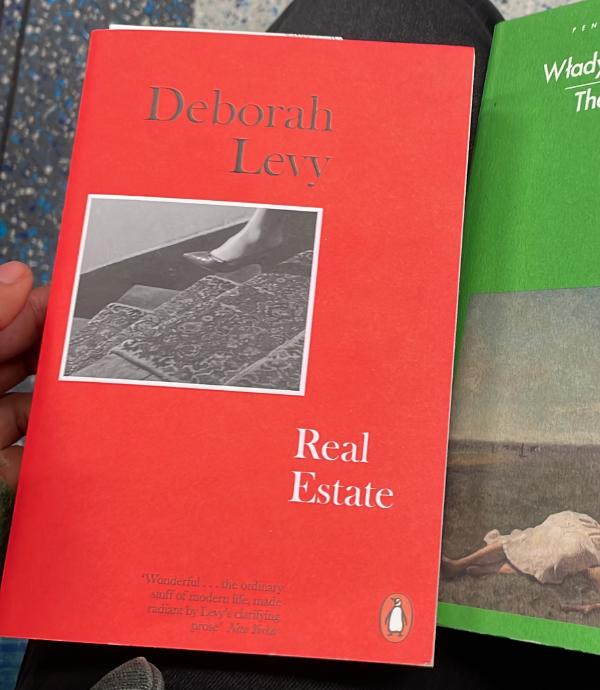

Real Estate is the final book in Deborah Levy’s Living Autobiography trilogy. Across the series, Deborah Levy writes about her life like she is both within it and also, at the exact same time, holding it up in front of her like an apple she can behold. She collapses the distance between herself; inside and out, as subject and object. This qualifies her for a position in my heart (and outside of it, being beheld by my heart like a lovely apple). In Real Estate, Deborah Levy begins by writing about Georgia O’Keeffe’s house in Santa Fe: her final house, a place to live and work at her own pace. As she insisted, it was something she had to have. It sounds like something we all have to have, or at least something I want to have quite badly. Deborah Levy continues: I was searching for a house in which I could live and work and make a world at my own pace, but even in my imagination this home was blurred, undefined, not real, or not realistic, or lacked realism.

If writing makes wishes real, in 1929 Virginia Woolf had manifested a Room of One’s Own for every woman in history present and future who has ever had a single thought. A room for Her to incubate Her thoughts and push them through a process of steady alchemy, from thought to writing to wish granted. Thinking needs a house and a room within that house and space to be alone and incubate — back back back into the woman’s head and forwards, out into the world or around the room.

Deborah Levy imagines a home that feels and actually is imaginary. She slowly fills it with things she finds delightful; an oval fireplace (the shape of an ostrich egg), a garden with a pomegranate tree, circular staircases, fountains, mosaics. The house is in her mind and it stays there, perfect and undefined. She tussles with how she goes about imagining it. Sometimes it is hazy and distant, sometimes it is clear. The wish for this home was intense, yet I could not place it geographically, nor did I know how to acheive such a spectacular house with my precarious income. Deborah Levy calls it her Unreal Estate because it lives solely in her imagination. She visits it frequently and rearranges the layout and the location, adds windows, tchotchkes and furniture.

Unreal Estate, a home imagined in your head. Could I make my writing into a wish from the Room Of My Own inside my own mind. Ha! Yes, or I would try. I could hear the estate agent breathing on the other side of the front door. I imagined he was scrolling through RightMove, breathing heavy with genuine lust at the sight of a luxury 3 bed penthouse in Southwark. I exhaled through my nose and told the Man From Spareroom that no, I don’t work from home (I work in my head and that is factually and semantically true). I don’t snore, neither does my boyfriend and neither does my husband.

Since 2015, an artist called Laura Yuile has been making a podcast called Asset Arrest. She invites a guest to go and view a residential property with her, pretending to be potential buyers or renters, and then they have a chat about what just happened, what they saw and what they think. Laura Yuile and her guests have viewed Embassy Gardens (that block of flats in Nine Elms with the Sky Pool, a residents only glass bottomed swimming pool that stretches like a bridge between two buildings), London City Island (that nub of land by Canning Town that’s crammed full of new builds), Hale Village (new build towers out in Tottenham Hale), a £12 million house in Kensington, a £27 million townhouse in Marylebone. Beyond London, Asset Arrest has visited properties in Hong Kong, penthouses and controversial housing developments in Berlin, new town developments and regeneration projects in Guangzhou, private student housing in Newcastle. In a Frieze Week special, Asset Arrest went undercover and visited a Property Investors trade show at the ExCel centre. The guests are artists, architects, academics, activists, urban designers, cultural geographers and that guy — Lord Matalas from TikTok. They discuss their work, where they live, and this wider theme of financialised housing and the neoliberal city.

As Asset Arrest, Laura Yuile also runs her own tours of luxury flats. Members of the public pick a property listing and she will email the estate agent or the developer, arrange the viewing and accompany them to it. Together they pose as prospective buyers or renters. A couple, friends, they might pretend to be related to each other. Laura Yuile calls it an ‘act of ungating’, artist acting as a facilitator so you can enter and behold the city’s luxury spaces — spaces that aren’t normally or necessarily available to you. Technically or legally, it’s lying or trespassing. Something about it feels like it’s not allowed, even though it’s just going to look at a flat you have no intention of buying or renting. In the grand karmic scheme of things, weighed up against the scale of the housing crisis, the cost of living crisis, skydiving wages and the yawning gap of wealth inequality, recession after recession after recession — this is morally neutral. But it still feels naughty.

Or at least, I feel naughty. Lying or trespassing my way to this floor to ceiling panoramic window. I think it’s also a third thing. It’s playing. I’m playing a part, playing a game, playing makebelieve. A world where I’m the wife of a man much richer and older than me. We have a global property portfolio, a collection we’re constantly adding little trophies and curiosities to. Our Unreal Estate. My husband has to be older and richer, that’s part of it. The dynamic has to be one where I’m a woman who is taken care of. I have to be in a position of power but also slightly distant from that power, maybe actually disempowered by the circumstance that affords me my power in the first place. It has to be complicated for me to feel good about it. The estate agent is the only audience, the perfect audience — he has to be here for it because he’s the only one that’s not in on the joke. I feel very particular about this fantasy, about getting it right and making sure he believes it. And why wouldn’t I? When fantasy is a richer world than the world of reality. In fantasy, I am literally richer. In reality, the Man From Spareroom is telling me about his weekly schedule, about how he gets up at 6AM and how he showers in the evenings. I am pressing my fingertips against the thick glass of the floor to ceiling window. I can see a splatter of birdshit on the other side, a layer of city-dust accumulated along the outer surface. My fingertips leave grey kiss prints, and I’m able to see that the inner glass is actually many inches apart from the outer glass. The Man From Spareroom says it’s important to discuss schedules when you’re sharing a bathroom with a stranger.

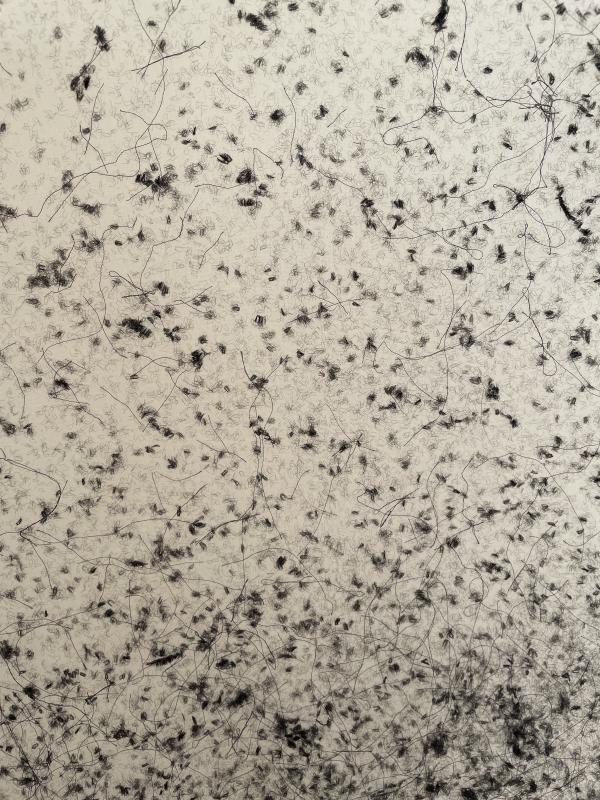

Anna Mud’s Moral Fibre is installed in a sunlit room, upstairs in Newcastle University’s Fine Art Degree Show. Long sheets of translucent white organza are tacked up along the wall. The fabric is so thin and sheer that you can see the texture of the room’s magnolia walls and the dust on the plug sockets. Across the organza, there are blossoming soft black patches. Anna Mud has positioned two wooden benches at the other end of the room. From this viewpoint it looks like black mould. Up close, you can see the patches are made of short, hazy fibres tangled into the organza— velvet fibres. They’re straight and splattered across the fabric like confetti. But from that bench along the far wall, you are a spectator beholding a terrible blooming pattern of black mould and you are listening to a soundtrack of someone coughing the same canned cough in a ryhthmic repeating loop from a speaker that is right next to you. There’s a wall text that slices the work open; rising rents and cost of living crisis means people can’t afford to heat their homes. With the UK’s cold damp climate this means black mould. With the UK’s rental crisis, this means landlords shirking their responsibility to prevent and remove the mould, this means tenants have to live in rooms full of black mould. Historically and traditionally, velvet was made from silk. It was a precious fabric, subject to English sumptuary laws that regulated clothing in relation to your social status. Velvet was exclusively worn by kings and nobility.

For a moment I am not standing up against the window with a panoramic view of the marshland, I am in the sunlit room with Anna Mud’s work. There’s a window open and a breeze is blowing in, it ruffles the bottom of the fabric. The organza and velvet flutters up on the breeze, away from the wall and disappearing into an elegant flying fold. Then it returns. Yes, fantasy is a richer and more beautiful world because it is endless and limitless and when reality returns you can lay the fantasy world across it and just see right through. The fantasy is translucent white organza, flickering across the wall. I scroll through @friends0ffriendz instagram carousels like it’s an interiors and lifestyle magazine curated just for me. It’s more attainable and realistic than browsing @themodernhouse. Maybe, like Deborah Levy, I like to tussle with the realism of things — even the things that only exist in my imagination.

I press my forehead against the panoramic window’s glass and imagine I am falling through it like water, out into the marshland or into a new kind of space. I have a powerful imagination, encountering a limit within it is so surprising it almost feels like an affront. The estate agent is knocking as he re-enters. He is thanking me, apologising because he has another viewing that he’s already late for. He seems genuinely sorry. He seems to believe I have access to power. I thank him and apologise too, even though I feel no remorse at all. And I tell the Man From Spareroom I’ll see him this evening, I call him darling and say love you before I hang up. I wish he’d said it back!

Rachel Whiteread collected over 100 dolls’ houses over a period of twenty years to make Place (Village). The installation is in the Young V&A in Bethnal Green, in a dark gallery where the dolls’ houses are stacked up on either side of a walkway, sloping down to you like you (the real viewer) are walking through a perfect valley between two miniature hillsides. The houses are lit from within, empty of furniture and people but there are different lampshades and curtains. At a glance, it feels cosy. Rachel Whiteread is better known for House, her very spectacular concrete cast of a Victorian terrace house in Mile End. The rest of the houses were torn down around it, the sculpture only stood for eleven weeks. A solitary mass that looked houseshaped. But it was solid, impenetrable, unlivable. It won Rachel Whiteread the Turner Prize. Here and now I am more interested in her dolls’ house valley because it’s the complete inverse of House. Unspectacular in scale, literally miniature. Dainty and precious and cute, rather than looming or imposing. Empty and full of negative space, real absence rather than the presence of absence.

Here and now, I am in the lift down to the ground floor. Here and now, empty space feels like a luxury. Like a possibility. Like it is waiting for me because I am the missing piece, I complete it. Empty space is a blank page waiting to be filled, waiting for my process of steady alchemy — thought, writing, wish granted. Truthfully, I’ve been doing all my thinking in borrowed space, full space, mass. The only space that’s my own is my bedroom my locker and my backpack and even then. I don’t want these concerns to sound petty or bourgeois, I don’t dream of private property. But I can’t help that I want what I want.

— My Unreal Estate. I realise that it’s not that expansive, I don’t want much. What I want is a desk up against a big window where you can see a large sky. Behind the desk there’s a long row of shelves with loads of books. They’re so close, I can just turn round and reach for things without getting up out of my seat. It’s very quiet and I am high up. If I look out, it’s just sky. But if I look down, I can see people and buses on the street below. There’s a rug under my feet, hand cream in a drawer by my knees, a suncatcher is dazzling little dots of light across the room. If I leave my desk to explore what’s outside the room, I can’t. I can’t imagine what’s on the other side of the door. Maybe I’m near a lido and a park, maybe I’m within a 5 minute walk to a tube station, maybe there’s a decent coffee shop down the road. But I think the rest of the flat is unrealistic. I don’t care about sofas and sidetables! I just know that I live there on my own! I am all alone with my thoughts and my quiet and my process of steady alchemy. No husband, no boyfriend, no Man From Spareroom, not even an estate agent — even though he is my perfect audience.

I check the time. It is 11:11. A double angel number. I wish I had a bigger imagination. I wish I wanted a display shelf for all my trainers, so I could line them up next to each other in one long queue, heel to toe. I wish I wanted a greenhouse, a ceramics studio, a balcony with tomato plants dying in dried up pots. I wish I wanted an Italian marble kitchen island, clawfoot bathtub, wine fridge, L shaped sofa, space for yoga and a dog and guests. Maybe I do want these things — I don’t know, I just can’t imagine them for myself. I just want a fucking spare room!!!! It doesn’t even have to be big!! I have so much distance to travel before I can access wanting more than that. I make a wish to close the gap, crunch my way from thought to wish to words to fantasy to reality.