Work!?

ZM

I have been thinking about work quite a lot. About the ways in which art is a kind of work. About whether artists make work or do work. About whether artists are therefore workers. About whether writing about art is also a kind of work. About whether I’m a worker too, please, even though I am middle class and white collar and I rarely get my hands dirty. About whether all work is exploitative, precarious, maybe work itself is the worst thing you could ever wind up doing in any given moment. When I kiss my wife goodbye in the morning, when she waves at me as I roll the car out the driveway of our suburban perfect home, when she says ‘have a great day at work honey!’ — what does that actually involve? I go to work, I’m at work, I’m working here! Making work, making it work, working hard or hardly working! Work — Rihanna (ft Drake).

All of that hinges on the assumption that art can be legitimately classified as a kind of work, and honestly, sometimes I’m not too sure about that classification! Making art is a desirous act. You make art because you want to, or because you have to, or because you need to, one way or the other! It just comes out, like sick, like snot, like tender love and affection. It requires the presence of desire, and desire is like… notably absent from any cultural or philosophical understanding of the nature of work. Work is work. You’re not meant to enjoy it, that’s why they pay you to do it, and if there was no money maybe there’d be no work. But there is money, so work is a necessary evil we must all suffer through because of the social contract or whatever. But then again, the cultural industry is an industry the same as any other. I am suspicious of attempts to understand cultural work as a hobby or an extravagance because — well, after 15 years of Tory austerity and 40 odd years of neoliberal political consensus, I wouldn’t be wildly off the mark in saying that undermining cultural work is a prelude to undermining cultural funding.

And anyway, work is everywhere. This is a work-ish world. We cannot understand a reality without it! Labour is a constituting force, it defines entire identities, entire social categories, we are all defined by our existence under capitalism.

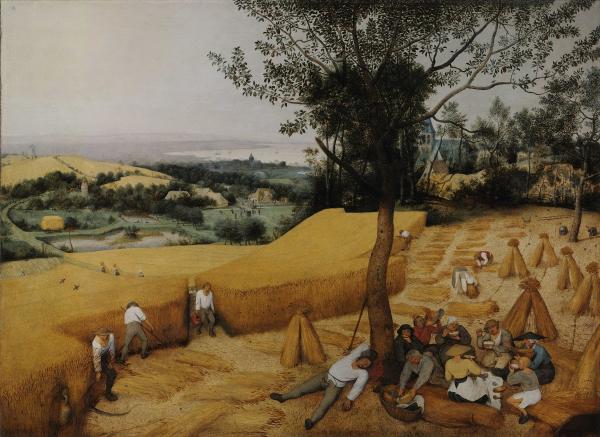

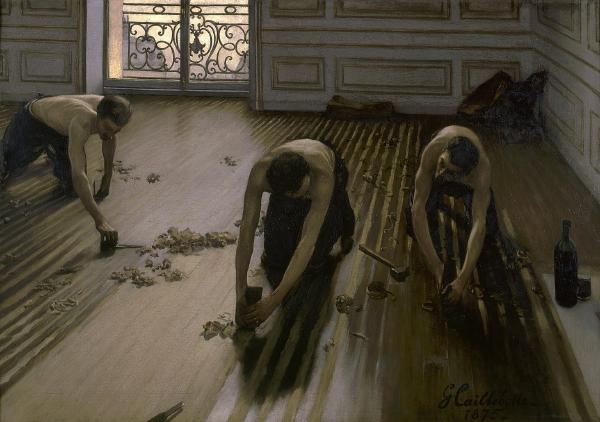

I have been thinking about work quite a lot. The way work appears in art. Bruegel the Elder’s painting of the Harvesters, literally a painting of work happening. Van Gogh’s the Potato Eaters, a painting where work is implicit but class is explicit. Millet’s Gleaners. Courbet’s Stonebreakers. Caillebotte’s Floorscrapers — one of my boyfriend’s favourite paintings! He says it’s because of the light! Because there is beauty in everything, even in drudgery! This is all Western Europe, where the artists’ bourgeois gaze beholds and renders the proletarian other. Maybe that’s where the romanticisation of manual labour comes in. In Soviet Russia, artists weren’t holed up in the academy, they were out in the provinces. Artists were workers because everyone was a worker, working towards the glory of the worker’s republic — at least, in theory. Stalin’s arts policy wasn’t necessarily progressive, and it wasn’t even necessarily about producing good art. But it did produce Socialist Realism, and an endless supply of paintings about work.

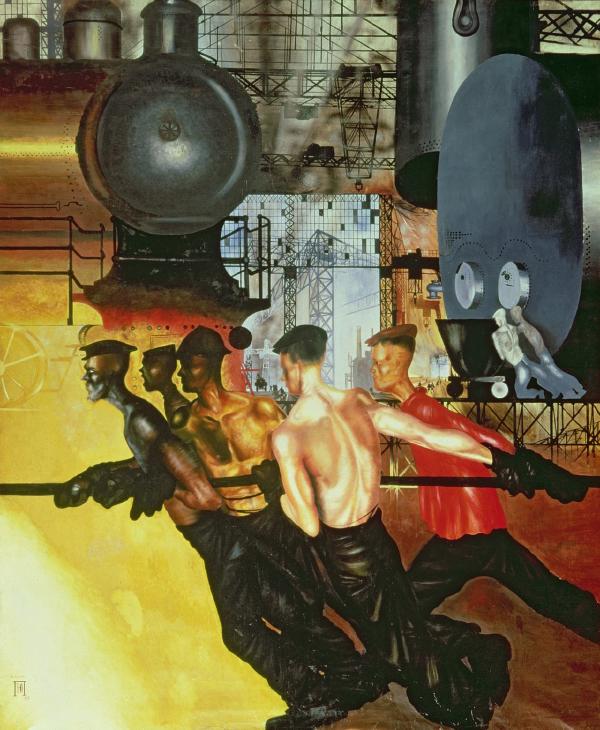

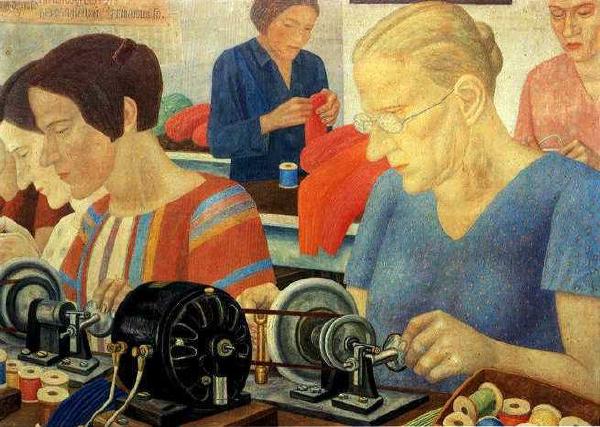

The genre contains this specific way of depicting workers and work. In Yuri Pimenov’s Increase the Productivity of Labour, five men haul or heave something in or out of the foundry flames. They are all (but one) barechested, diagonal with exertion, stoic and focused. Pavel Filonov’s Record Breaking Workers at the Factory, women hunch over sewing machines in cherry red colours. Posterised paintings of cheerful, red cheeked workers, arms raising their sickles to the sky. Or raising a red flag. Or both red flag and sickle. Always smiling. Vladimir Lenin salutes a crowd of cheering men in work jackets, red flags waving behind him. They’re happy to see him, happy to hear him. Women working a field, golden with wheat and sunlight. The New Soviet Man, Alexei Stakhanov, a coal miner from Donbas. On 31st August 1935 he mined 102 tons of coal in less than 6 hours, 14 times his quota. His face was printed on posters and in newspapers as an example for other workers to follow. It gave birth to a whole Stakhanovite movement, workers who overshot their production targets were called Stakhanovites, a kind of national hero. It’s a different kind of romanticisation, but nonetheless…

I have been thinking about work quite a lot. I think it’s everywhere, everyone is kind of obsessed with it, including me. I went on holiday in June, my boyfriend took me to Venice for my birthday, my 30th birthday! Big number, round number. Even though I was on holiday, and even though it was my big beautiful birthday, I obviously still felt like I had to go and see some art. Because that’s my job — duh! I love it! So I have to always engage with art. Never stop thinking about art, always find ways to be looking at art. I was in Venice for the first time, in a Biennale year, and I’ve never been! The art olympics, art Eurovision, it’s like this thing that everyone has been to in some capacity — everyone but me! So I dragged my boyfriend across the island in 30 degree heat to go and look at some art. And I looked at the art. And I thought — who the fuck cares? NOT ME. Oh my god, I didn’t care. I was in a brand new city. It was hot. We were staying on the mainland, in the Italian version of Butlins and there was a swimming pool. I wanted to go for a swim, do backstroke and look up at the very blue sky. I wanted to drink aperols with olives in them, so salty weird and icy sweet. I wanted to go up the tower and have a look in the basilica and eat hazelnut gelato and try an oyster for the first time. Who the fuck cares about art?! These dry national pavillions, this weird soft power flex, cultural legitimation of the nation state as a concept. It was 30 degrees and I was getting a tan in the shade. My poor, gorgeous boyfriend! Enduring the art, just for me, and I didn’t even care to look long enough to understand what was going on.

We got to the Giardini and I ran past Switzerland, Venezuela, Bolivia, Japan, Korea, Germany, Canada, Britain and France. I ran past Australia, Scandinavia, Uruguay, over the bridge and straight to the eco toilets. I did a poo on a roll of foil. I flushed with my foot, pumping the roll of foil round, dragging the turd in a line, down a hole, into the void. When I came out, my boyfriend was still shitting or rolling his own foiled poo down into the eco-void. So I went in to Romania’s pavillion to wait.

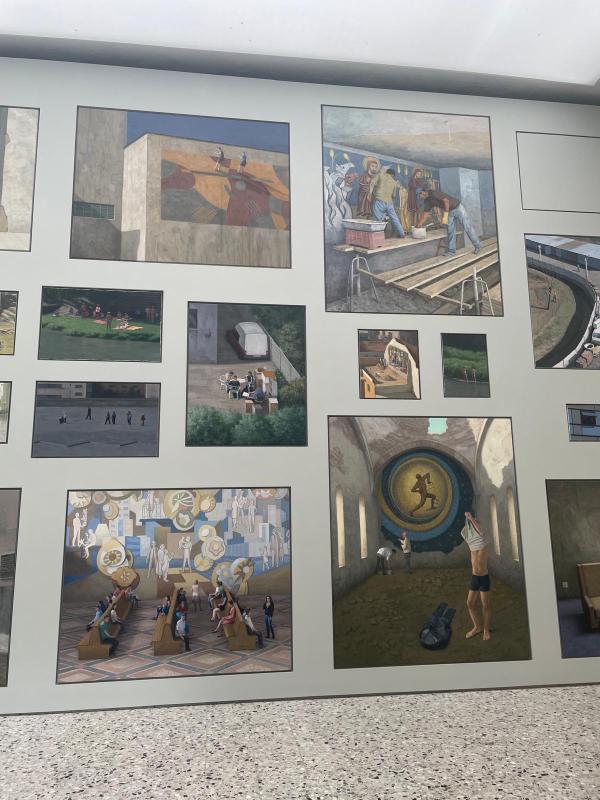

On the inside, Romania’s pavillion was exceptionally wide and not very deep. A room that felt panoramic. Full of Serban Savu’s installation, What Work Is. On the wide wall facing me, about 40 paintings hung in one big overwhelming salon-style cluster.

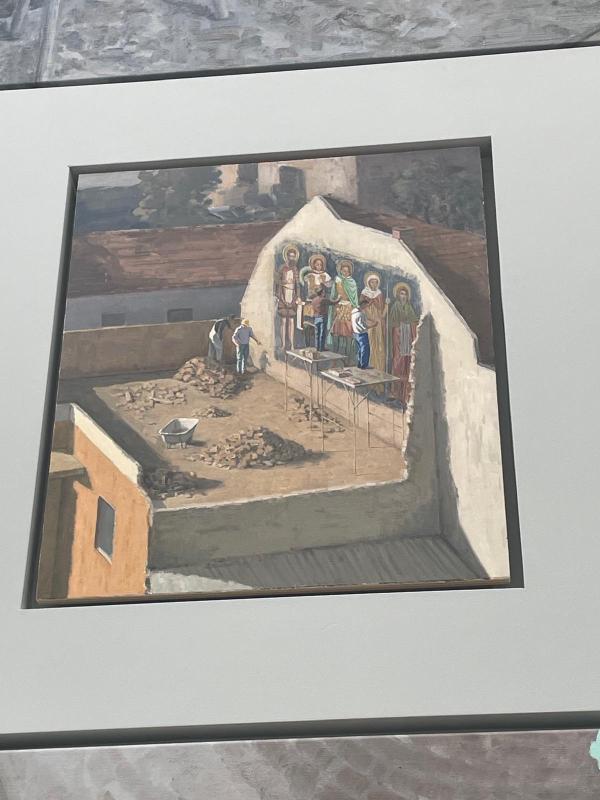

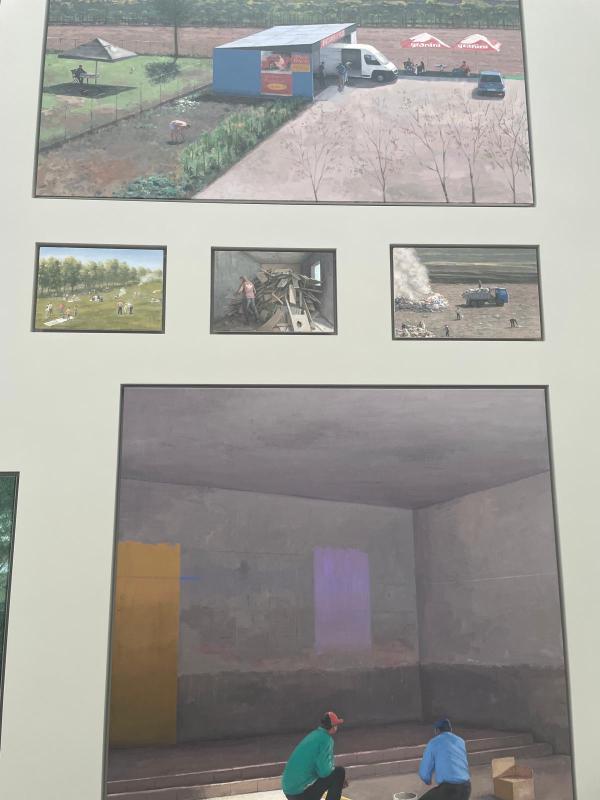

Zoomed out drone’s eye view of a man standing on the back of a flat bed truck, driving away from a pile of burning rubbish. A man in an Adidas tshirt interacts with a pile of plywood that takes up half of an empty room. A group of barechested men dig out an excavation site, exposing a dirt stairwell and a mural of horses, wild boars and cavemen. Another drone’s eye view of a half demolished house with only half a wall standing, two men in hard hats shift piles of bricks and a scaffolding tower lifts two other men up to eyelevel as they restore or paint a mural of 5 saints. Two figures perch on the side of a road in heavy jackets, the expanse around them is grey and bare. A man sleeps on a sofa next to a switchboard with trailing wires. A man pops his head out of an apartment window, he is wearing a hardhat, the painting is cropped tightly around the window and the window is cropped tightly around his face. A drone’s eye view of a farm track with concrete grey yard, corrugated metal outhouses, bags of grit and sand, three figures gathered chatting in blue overalls. A figure unloads a truck in the shadow of two other buildings. Three men laze on a grassy hill, one of them is lying propped up by a fallen tree. Two men abseil down the side face of a concrete building in hardhats.

All the images were painted in that modern, hazy way. The kind of render where you can tell some kind of screen has mediated the image-making — either painted from a photo or pulled from the internet. All flat and milky. Images of work. Images of leisure. Images of people at rest. There were many paintings of people sleeping in empty spaces. There were many paintings from up high, perspective on a tilt from that drone’s eye shot. The paintings were all different sizes. Some quite massive, some the size of a notebook. The floor to ceiling, wide wall panoramic install was overwhelming and flat — all the paintings were flush with the wall, nestled into perfectly cut alcoves. It felt less like a salon hang and more like an enormous altarpiece, but I still don’t know if that likeness was just a projection of my desire to be elsewhere. Specifically, my desire to be in the basilica, gazing up at the Pala d’Oro — that Byzantine Dark Ages masterpiece, golden altar with enamelled paintings of saints and angels. No, no — they feel parallel in their flatness, the clusters, many images forming one wide block. The labouring body, images of work. The divine body, celestial image.

I have been thinking about work quite a lot. I think paintings of work are the only kind of paintings. All paintings are like records of work, they document the work, manifest work into a material, an image. Images are work! All painting is work! —— I don’t know why but I was more interested in Serban Savu’s paintings of people who were asleep on the job. I was more interested in the images of rest. It’s funny that in my mind, I’m holding these images of rest up like they are images that do not contain work, even as a remnant halo, even though rest exists in work’s absence. Work is everywhere! It’s there, even when it’s not!

Sure, I’m meant to be writing about images of work. I’m meant to be working! But really, I just want to stretch out in it’s absence. I want to lie in bed and snooze until 9.30 every morning. I just want to read through obscure wikipedia pages on my phone. I want to go to the lido and swim in the middle of the day. I want to eat an apple and stare at the sky, watch the sun peep past grey clouds. I don’t want to do work any more, because I can’t stop thinking about it! Paintings of work, art as work, absence and presence, materialising labour. Maybe there’s an unfortunate overlap in terminology, where art’s work is both a noun and a verb, descriptor and action. An artist works to make a work of art. The work is the labour and the product and it’s all I can think about.