Empty Alcove / Rotting Figure

ZM

Outside it is roasting hot, but Chisenhale’s gallery is cold. In front of the entry ramp, there is a film by Dan Guthrie called Empty Alcove. It is playing longways on a floor to ceiling pole. I sit down. My thighs are hot and they stick to the chair. It takes me a minute to pick up what’s going on. The film is mostly silent, mostly still. A tight shot of an empty stone alcove, an empty stone shelf. The alcove is right at the top of the building, nestled under the roof as it tapers up into a tight gable. A sliver of a black clockface at the bottom of the frame. The sky is blue, the only movement is the wisps of clouds passing. The only sounds are ambient street noise, kids chatting in the playground, planes passing overhead, birdsong. The film has captions, listing the contents of this pleasant ambient noise.

Then the film shifts, or loops. Same scene but with audio description instead of captions. The first voice is very neutral, describing the image: ‘A stationary shot of the top of a sandy stone building with a narrow gabled roof. An arched alcove, a recess in the wall, is in the centre of the frame and below this is a protruding ledge.’ A second voice replies, irritated, correcting: ‘Haven’t you forgotten a few things?’ The clock face, the bell. The first neutral voice reissues the description, this time with correction. The second voice makes a second correction: ‘Surely you’ve got to acknowledge that something’s missing here? Why would there be a ledge with nothing on it?’ They go back and forth, in exasperated dialogue with each other. The neutral voice continually attempts to standardise the descriptions, the irritated voice continually interrupting to push for a description that critically questions what the image actually contains — and why, what might be going on behind or around the image. Until, the irritated voice says, ‘as we’re looking at it now, it is just a boring old building with an old clock that’s not got anything offensive stuck on the side of it for all to see. Just a shame that this isn’t what it looks like in the real world… at least for now.’

— Not to break perfect critical suspension of disbelief, but as an aside: I realise I could fill you in, because there are bits of this story you may not know. As I tell you about this work, I am making a series of choices: what I describe, how I describe it, what I leave out, what I allude to, what I mention in passing, what I avoid mentioning entirely. I cannot describe it all. In fact, I don’t want to. I feel I shouldn’t. I realise that that decision (what to conceal, what to reveal) has been made very clearly by the artist — the mechanics of this decision, the balance, the spread weight of the tone — this has been struck. The artist’s choices don’t dictate my own, but they determine something particular. By departing from the artist’s choices, I would tip that balance and the particular thing would fall apart. Something else would come up, something I don’t want to bring up. So I am writing this review carefully, aware of the way words reveal and determine things.

EMPTY ALCOVE/ROTTING FIGURE is a commission in three parts. The film of the Empty Alcove, another film called Rotting Figure, and a digital archive. The digital archive is home to a body of research that supplements the two films in the gallery — there’s a journal with texts by Dan Guthrie and other writers who have been invited to respond to the work, and a timeline that traces the history of the Blackboy Clock in Stroud —

The Blackboy Clock is a clock in Stroud, a small town in Gloucestershire. It sits in a little alcove on the front of a building, what is now a block of residential apartments, opposite a primary school. Under the alcove there’s a black clockface. In the alcove there is a black bell and a statue of a black figure holding a black club. The black figure is small, maybe a child, maybe a boy —

The timeline traces the history around this statue: when it was made, when it was relocated, when it broke, when it was restored. As the timeline enters the 20th Century, the timeline tracks Dan Guthrie’s family history: when his maternal grandparents moved to Stroud, when he was born, when he started primary school — charting his relationship and proximity to the clock and its figure. In the 21st Century the timeline starts to track a wider conversation: Historic England issuing statements on contested heritage, Coulston’s statue bellyflopping into the Bristol Harbour, Stroud District Council, DCMS, Culture Secretary, Conservative MPs, taskforces and review panels — everyone who’s anyone with a statement, a process, a recommendation.

The threads come together, depicting a long relationship between the artist and the clock, the clock and the town, the clock and a conversation about what we as a society should do about objects with contested histories in the public realm. The clock and public organisations and bodies that are meant to represent the will of the people, the way the clock’s fate has been determined by the slow movement of these bodies and their bureaucratic processes, the way the clock has actually been protected by terminology like historical importance, contested heritage, or protected by the understanding that we as a society have a duty to preserve and interpret things that are abhorrent to us. The clock has endured through time, through bizarre chance and the small c conservatism of bureacracy — the inclination to conserve what is there without critically reflecting on whether the thing being preserved is worthy of preservation. The law protects this object because of this endurance, like endurance is a sign of worthiness, importance, a divine right to existence. It is an ongoing timeline.

There is no point where Dan Guthrie shows us an image of the figure in the alcove. He presents us with the empty alcove. He presents us with the images and research around the figure, the news headlines, the statements, the opinion, the action, the papertrail. The closest we get is Rotting Figure.

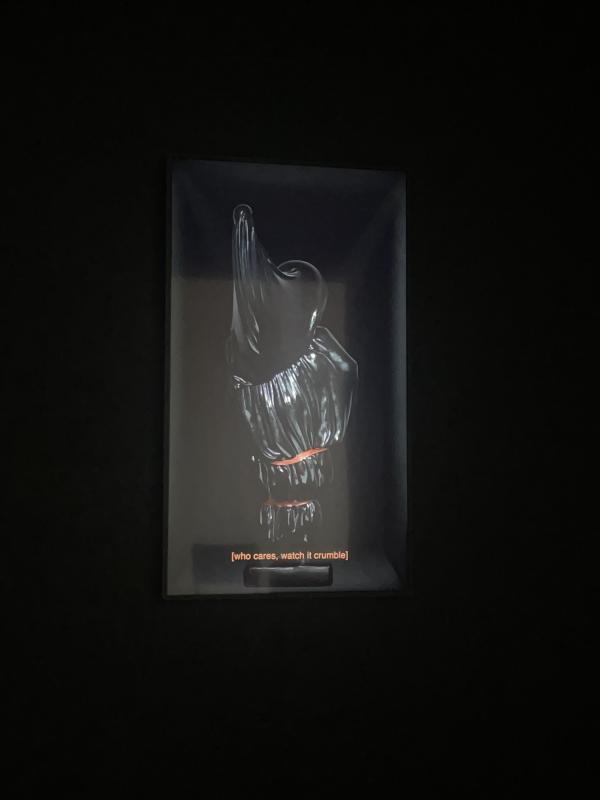

The second half of the gallery is taken up by a massive black box, a room within the room, so big it almost skims the ceiling. Round the back wall, the box has an open side. It is black within, and there is a second film playing on a screen. An item wrapped in a black bin bag, it looks like a small figure, holding a club. The film has a creepy horror soundtrack: ominous creaks, groaning wood — then something cracks, I jump in my chair. The figure has collapsed slightly. The club is slightly lower, the silhouette has deflated. Captions flash up: ‘black mass rotting beneath’. More creaks, more slithering unease — another crack. The figure collapses further. And again, and again. We watch it disintegrate at the hands of mysterious invisible forces. Until it is a festering pile slumped at the bottom of the screen. We never see what’s underneath the black bin bag.

I am interested in the splinter under the skin of this show. The artist’s choice to conceal the image of the statue, determining a balance, revealing something particular: desire, destruction, desire for destruction, desire and destruction, destruction as a kind of desire, made manifest, destruction as a container for desire, made vessel, destruction as a force of action that clears space for desire to flow through.

This echoing black box, half underground, half cold and alone in the gallery. I feel like I am witnessing something weird and unreal. A spirited up fever dream. It is satisfying, horrifying. I want to cheer as this unseen figure rots into soup. Maybe, yes, it is because I am spilling over with destructive impulses of my own. Maybe it is uncanny to watch these same impulses manifest in a space, a moment of recognition, looking someone in the eye and knowing —

On the digital archive’s journal, there’s a text by Lola Olufemi called LET’S PUT IT PLAINLY FOR ONCE. She writes: ‘I know my dreams of destruction have a pedagogical function. I know they exalt my consciousness.’ I want those two sentences tattooed on the shoulders of my soul. Yes. I too dream of destruction. I feel it is a productive force, a creative urge, a chance, an inevitability, a horizon to run to, a portal a portal a portal. I want to fling my body through the doorway it opens up. I want to take a knife to the veil of the world and open that doorway up for myself.

I am glad Dan Guthrie hasn’t reproduced the image of the figure — it would be a conservative thing to say ‘the role of the artist is to hold a mirror up to society’. To who! For what! What the fuck even IS society?? Reflection should not be an end point, it is a process! It is a pathway —towards destruction! ~Holding a mirror up to society~ tasks the artist with bearing the burden of certainty, determination, closure. ~A mirror to society~ is the framing of an end point, a barrier, a full stop. Real life bounces back out at you and closes the loop, certain, definite. Destruction acts as an opening: a dream, a vision, it makes way for uncertainty, it is a portal. A nothing begs for something to come in and fill the gap. It is a question, a beginning, an open space. I have no fear of destruction! The shape of my fear is what is certain, what is known, proven, solid, fated and unmovable. I want the world to become liquid, rippling dreamspace. I want to pour it into my hands, fling it at the walls, spirit up different versions, a vision of birdsong, blue skies, pleasant ambient noise.

Within the spirited dreamspace of the gallery, of the artist’s imagination, maybe these visions of destruction can be played out to their natural conclusion. Dan Guthrie’s show at Chisenhale is like an anti-monument, a vision, a version. It exists in the realm of his imagination, in ours, in the imagination of the writers gathered on the digital archive’s journal. Maybe the portal was within us all this time! Ha! I walk back up the ramp, back out of the portal pocket and into the heat.

Dan Guthrie’s Empty Alcove / Rotting Figure is on at Chisenhale until 17th August. If you want to have a peep at the Digital Archive, here’s a link.