Gaza Biennale (UK Jinnaah)

ZM

Biennials are socially constructed falsehoods. Like bitcoin, like astrology, they are not actually real (but we all believe in them, and that makes them real). I went to Venice for the first time last Summer, a birthday present from my boyfriend that landed us in peak biennale art tourist season. We stayed on the mainland, in Italian Butlins. We swam in the mornings, with the screaming toddlers, then got the shuttle bus over a bridge, onto the island. Me and him and the cruise ship hoards. None of Venice seemed real. It was all like a fever dream, a truly bizarre concept for what and how a city could be. On the first day we walked over bridges, past palazzos and through piazzas, dangled our legs over the canal, tilted our faces up to squint at the sun as it screamed over San Marco’s square. We crammed into the belly of a clipper, slung below the waterline on our way over the lagoon to the Giardini and the biennale. I half-hated it. I’m sorry to say it. The Giardini and the art was the least weird thing I saw that day. The most boring too. Venice around the biennial was so weird! All the angels and marble, striped columns and backstreets, boats and curled carvings and streets looking straight out onto the water and beyond, the Adriatic Sea. The art felt trad, normal, a conservative form against the rest of that blown out Gothic-alien landscape.

I couldn’t locate my discomfort in the moment. Couldn’t tell if I was chafing against the scale, the spectacle, the idea binding it all. I shook it off, screamed for England and Jude Bellingham’s divine bicycle kick, cried in front of the Pala D’Oro. But a year later, my thoughts still snag on the idea of a Biennale, I still itch at that discomfort.

I remember reading Skye Arundhati Thomas’ essay on the 2019 Venice Biennale, the opening that sliced between Christoph Büchel’s work — parking a boat called the Barca Nostra in the canal next to the Arsenale. In 2015 the Barca Nostra was making a crossing from Libya to Lampedusa when it capsized, it was carrying nearly 800 people, all fleeing and seeking refuge in Europe. Only 28 people survived. The Barca Nostra was salvaged by the Italian Navy, Büchel repurposed it into an artwork within the Biennale’s main exhibition, May You Live in Interesting Times. Sky Arundhati Thomas’ essay condemned the work as a shallow blockbuster that reeked of the artist’s privilege, an insult, a sick reminder that borders are social constructs, made real by violence. She writes about the added insult and irony of posing these questions, like they are critical and abstract, within the container of the Venice Biennale — a curatorial flex where countries have national pavilions, the art world Olympics, soft cultural diplomacy funded and produced by actual national governments. This isn’t a neutral arena where the idea of the nation state can be interrogated, even the act of interrogation becomes a performance, a kind of nationalist display.

Before reading that essay, before actually going to Venice, before being disappointed by the biennale to end all Biennales — this whole set of concerns felt very abstract and fictional to me. I don’t know whether I should say Biennale or biennial, both feel pretentious. It is all so big, so expensive, so grand and sweeping and simple. This is all a kind of art that bears no relationship to my actual real life, the things I am concerned with. And it makes no attempt to close the gap, reach a hand across the void between us. It is enormous art, literally — a huge boat with a gash in its hull, spectre of death, parked up on the canal super yachts in front of a VB branded coffeeshop, bumper to bumper with the super yachts and vaporettos. Art crowds with sun hats and Loewe handbags. Reading about it, seeing it, it is like fiction, like theatre, both banal and absurd. What is a biennale? What is even the point? What is it doing? Who does it serve? Who is its public? What are you meant to think about, or experience when you’re standing in the middle of the Giardini, the pavilions, monuments to violence? Is there any way to make that not feel gross? Is there any chance at interrogation, complexity? How are you meant to interrogate an idea like the nation state in the first place? Who even believes in borders? In bitcoin? In violence? Who gives a fuck about a biennale???

Towards the end of last year I started seeing graphics pop up on Instagram about Gaza Biennale. Clips from videos, bits: they were gathering images of work from artists in Gaza, projecting these images onto the sides of institutions. At the Turner Prize announcement, when a crowd gathered to call for Tate to divest from Outset Contemporary Art Fund and the Zabludowicz Art Trust, these images flashed along the side of the Tate Britain. At the opening of New Contemporaries at the ICA, calling on both organisations to drop the funding from Bloomberg Philanthropies. I managed to miss both these moments, only catching them when they made their way onto the internet. Still, the energy of that activity was palpable through my phone screen. Gonzo, guerrilla curation, not waiting for institutional approval, making a container where geography, the idea of the nation state, political spectacle, all of the above were being crunched up and collapsed.

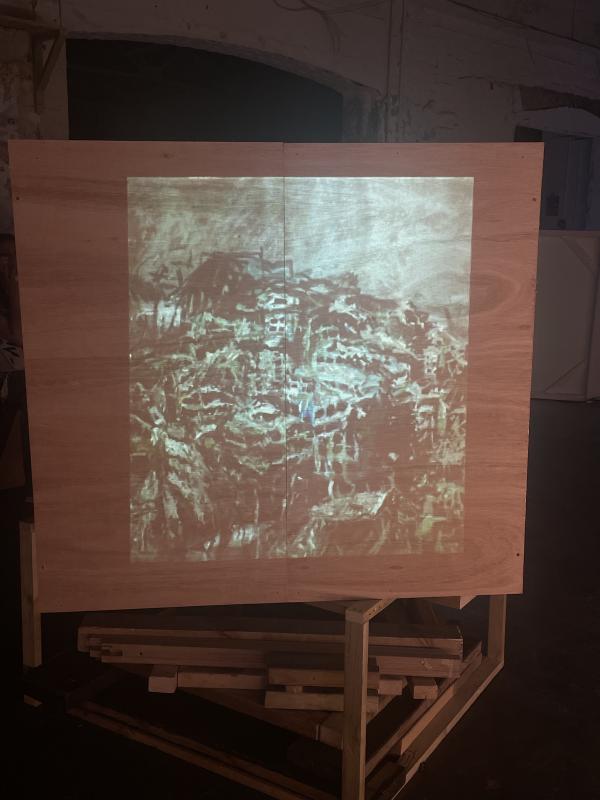

At the end of May, Gaza Biennale staged their first exhibition inside a gallery: Upon the Ruins of this World at Ugly Duck, a project space down in Bermondsey, spitting distance from the White Cube. The space was full of wood offcuts and assemblage, boxes cobbled together into screens, distressed and discordant. Over the screens, slideshows shifted. I sat on a box in the dark. The work of 50 artists from Gaza, hauled over the internet, now before my eyes.

A biro drawing. Three figures huddled into a ball, arms wrapping over each other and interlaced like the petals of a rose as it unfurls. Faces between these limbs, eyes wide. These were rounded bodies, like Henry Moore rounded his forms, smooth like sea glass and pebbles. No sharp angles, no cartooning, just the curve of a neck, a back, bowed over in the tightest embrace.

A landscape of a ruined city, painted and dripping. Window blurs into wall blurs into the husk of a tower’s shell blurs into the horizon and it is all covered in harsh black shadow. The paint looked scratchy, liquid, like it had been applied quickly, like it had been carved out of itself, like it was melting and moving as it took shape. It is less a skyline and more of a pile, tapering up into a point. I have no sense of scale, no orientation within it. My eye just sinks and sinks, lower, deeper, within.

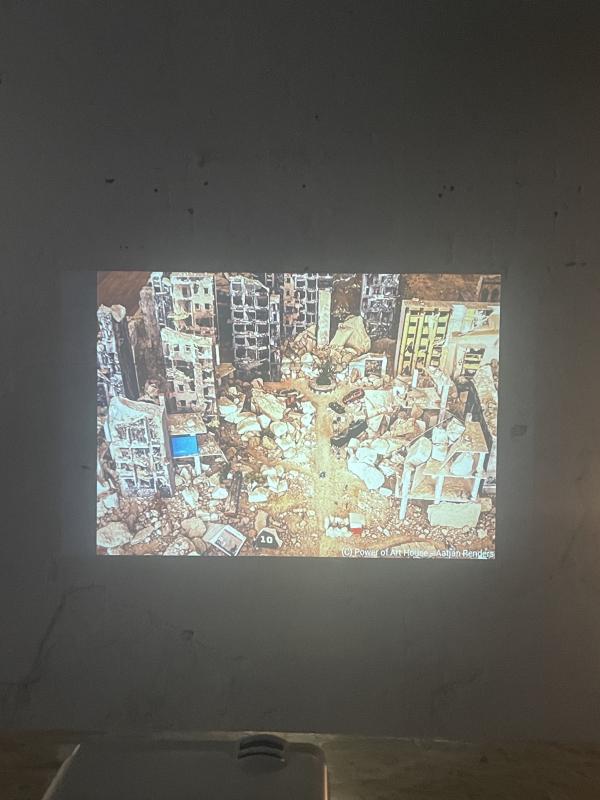

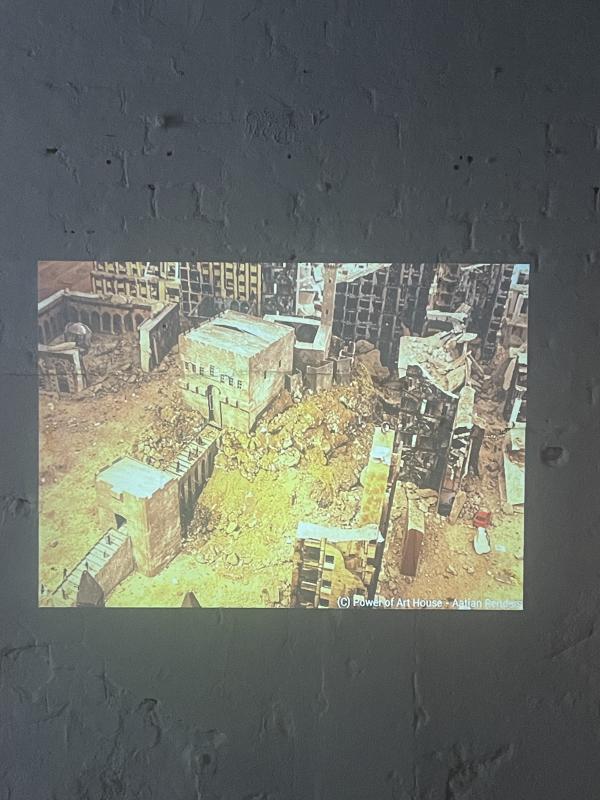

Then two images — similar but on the other side of the room. I can’t tell if they are paintings, drawings, photographs of a bombed out city from above, photographs of a miniature model of a city. The image has a texture that feels like eye fuzz, grit, pixel blur, any and all of these things. I try and focus on the size and shape of the windows, the colours, the shadows, try to pick out their depth and gauge a sense of scale from there. The rubble is very large, more likely to be a miniature model. No — those aren’t shadows, those are lines, shading. That newspaper is bigger than that window. If this was a photograph, what perspective would it even be shot from? How could this ever be real? It fucks with what I understand as believable, I can’t understand it as true, and still — I have seen those images, from when the BBC was finally allowed to fly a drone over northern Gaza. The buildings, a city turned to literal dust, literally flattened, an expanse that is almost liquid it has been so completely destroyed. As I am writing I am trying to google it, I cannot find the single exact image I am thinking of, because there are so many images of Gaza that fit this description. It defies time, defies my belief, I know it is real and I cannot metabolise it. It is the horror of standing at an edge before a sickening drop, the horror just as the rollercoaster tips over the highest peak — looking down over something, creeping dread. The image, this image, this horror. There is a sense of flatness between the background and foreground, like the pictorial plane is collapsing in on itself, levelling, not as deep and pushing me out, my eye skimming over and not getting a way in entirely — the image flips before I am really able to figure it out.

A figure carved from wood. The figure is also rounded out, balled up, child’s pose with its knees to its chest, arms hugging in, lying on its side. The carved figure has been laid out on the ground, on mud and dried grass and bits of blasted stone. It looks like it has always been there, like it could never be anywhere else. The figure’s head is round, blank, smooth, featureless. From head to toe, it smooths out to a point — makes it feel like it could be here in the ground or curled tight between fingers into a fist. Ground, fist, gallery. I want it to remain over there, wherever it is, on the ground. I want to ball my fist here, feel my nails dig into my palm. Reciprocal motion between me and it, I feel its absence, I feel it within my grasp as it touches the ground, my palms kiss the ground even through my closed fist — it touches the ground for me.

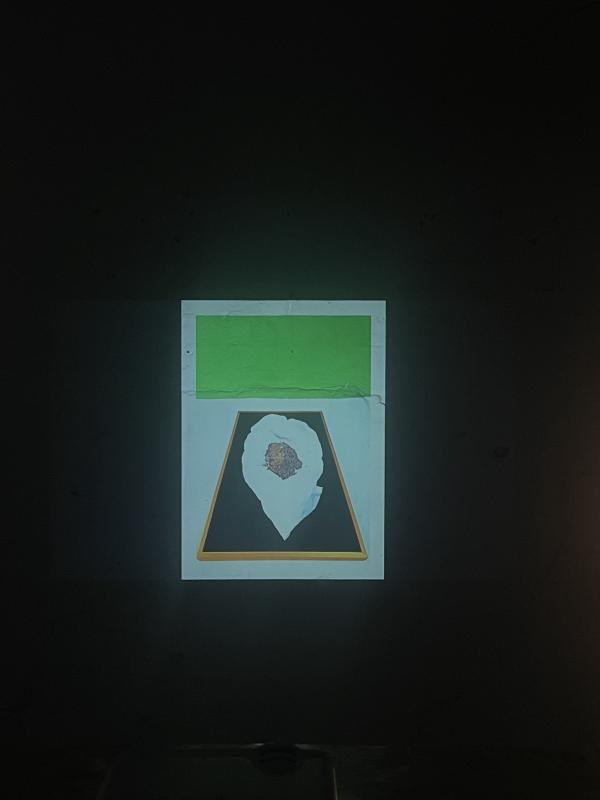

Another image I can’t quite work out. It has so much mystery within it. Two rectangles: one is lurid green and landscape, the other is black with a gold frame, portrait and disappearing towards a vanishing point on the horizon of the green rectangle. In the middle of the black rectangle there’s a white crumpled shape, like an upside down tear. And what looks like a small brown rock nestled into its folds. I can’t tell if this is a photograph of an installation, or a weird assemblage, found or constructed. Maybe it is also a very precise painting, collage, drawing. Even more confusing for my eye than the two images of the ruined city, the images that could be photos or paintings, the dread and illusion. I don’t know what manner of objects I am even looking at, parsing a purpose or meaning is completely futile. And under that, the deeper confusion that — of all the things this could mean, it could also equally mean nothing. It could be something with an absence of meaning, something that rejects meaning, something that exists on a plane beyond anything as trite as meaning. I think, at the very least, that the thing nestled into the crumpled white — I think that is a rock.

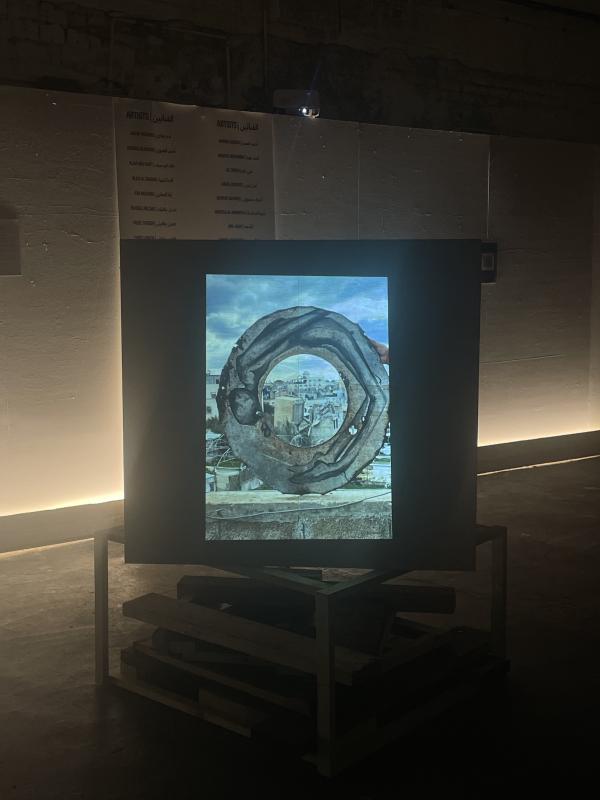

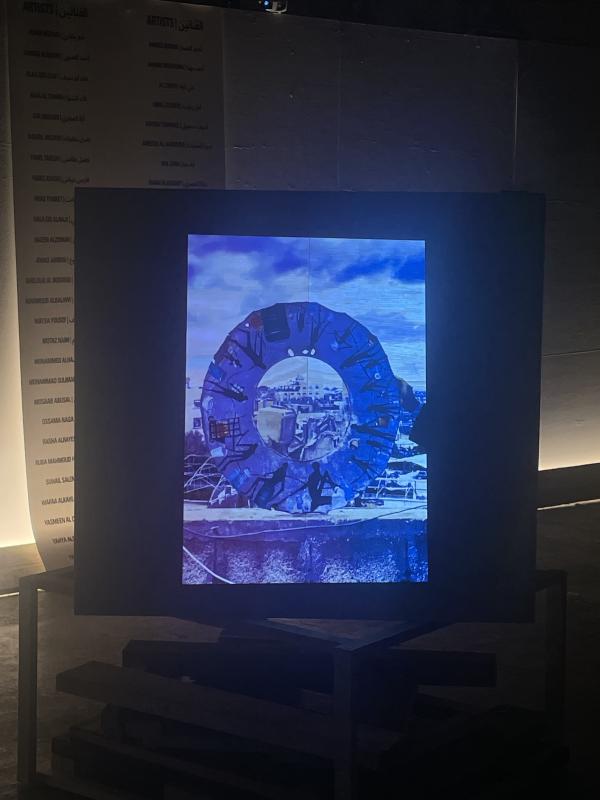

Two last photos of sculptures that could make me cry. Concrete rings the size of tyres, balanced on a wall overlooking the street and the sky. The artist’s hand is in the side of the frame, holding the sculptures upright. The wheels, the rings, they have flat surfaces. The artist has used them as a vessel for an image. In one, a figure curves around the entire ring, bending back in a graceful arc, head almost touching their toes from behind. In the other, slender shadowy figures go about their day, wheeling around from the bottom to the top. The images painted on these sculptures are interesting enough, but I can’t focus on them. Instead I am looking through the middle of these concrete rings, circles of the sky over Gaza. Buildings, half broken, a skyline and sky. They are like portals, viewfinders, I cannot stop looking. A perfect droplet of an image. I am here in the dark in London, looking at an image of the sky halfway across the world. It is projected on this slice of wood and I am gazing into it and it is beautiful. I look so hard, the projection almost shimmers. I feel like I could cut it out, peel it off the wood, roll it up and take it home with me. I wish I could. I would flatten the circle back out over my bedroom wall, a new window for me to see across the sea, over continents. I would reach out my hand, try to feel try to reach across, pull something through and collapse the distance. Sky, a hole full of the sky.

The biennale to end all Biennales over in Venice felt like it was speaking to me across a void. At odds with the underwater city it had landed in, not quite catching onto the alien energy and visual texture sprawling out over the rest of the lagoon. It was normal and distant, grand and absurd. The Gaza Biennale was the exact opposite in every way, and better off for it. Collapsing and swallowing geography. Fucking up and with your own understanding of how a nation state could exist on the global stage, for why, for who, for what purpose, which nation state even gets a foot on that global stage in the first place. Using political spectacle to shrink scale, divert attention, hold our eyes and force us to bear witness. When the world and its institutions look away, what does it mean to hold eye contact? To bear the act of seeing, looking?

Maybe then it also fucks with the very idea of what a biennale even is, the format and its heft, maybe that was also being recalibrated. Rather than national pavilions, rather than bringing the world in on one place, colonial great exhibition model, global buffet. Maybe instead it’s flipping the geographical or spatial terms: taking one place out across the world. The activity I’ve written about between the ICA, Tate and Ugly Duck has been organised by Gaza Biennale’s UK Jinnaah, Jinnaah roughly translates to pavilion or wing. The activity has been grassroots, localised, specific, responding to where in the world it is landing. There are 13 other pavilions in Berlin, Valencia, Toronto, Sarajevo etc — it is collapsing, swallowing geography. Hauling these images over the internet, showing slices of the sky over Gaza and blasting it across the world. That is an artistic intervention all on its own.

And it is all of that, sure. But it is also just art. No monuments, no blown out sense of scale to make me feel like a stupid mouse, no weird snag where context folds in on itself and complicates the gesture. Just art. Straight up. I meet it, person to person. I remain sensitive, alive to the weirdness of art in any moment, but particularly this moment. I cannot help it, I do give a fuck about that.

Gaza Biennale’s show, Upon the Ruins of This World, was on at Ugly Duck down in Bermondsey from 28th May - 1st June. Here’s an ig link to the full programme, but keep an eye on their instagram for future activity