Grey Unpleasant Land

ZM

I will tell you one thing. I didn’t get this job for nothing. They have no idea who I am, but they soon will! For the most part, I am biding my time. I lay low in the gallery, in the corners, at doorways. I hide in plain sight. Visitors expect to see me, or, they don’t register seeing me — even when they look right at me. Sometimes the curators rush past and send me a sidelong glance, a smile, but ah, I regret, not much. No, no. Galleries are feudal systems, if you ask me. Director King, curatorial lord, invigilator as peasant or serf — I appear before you now as an invigilator, but I roam free! A humble vagabond. A blessing, a blessing.

England is property, I will tell you that for free. Land sovereignty, the feudal system, William the Conqueror, 1066. It all goes back to the Middle Ages! It always does. It goes: country, land, property, people. William the Bastard stormed in from Normandy, confiscated land and property from those sheepish Anglo-Saxons, granted it instead to his own lords and few English friends. The land was a kind of payment in exchange for fealty — pledges of allegiance, oaths sworn over sainted relics, in acceptance of William’s Kingship. The lords were vassals, subservients, subordinates. They only got the land because they accepted William as their superior. Land got parcelled up into hierarchies, you see? Yes, yes. One man sits above another, the supremacy of the English crown — a legal fiction, but nonetheless… By the time of the Domesday book, some 20 years later, there was no allodial land left in England — that is, land without a supreme or superior landlord. Every square inch of this godforsaken island had been sized up and handed out to some kneeling lord. The lords held the land by the grace of the King, they gave out their land to mesne lords, who were their vassals in turn, to Vogts, to Esquires, to Gentlemen, to Yeomen, to Husbandmen— on and on, downwards until it reached the peasants and serfs.

Land is gifted in exchange for services and incidents, obligations due from the vassal to his lord, rights held by the lord over his vassal. Rent, labour, military services, ecclesiastical services — forms of tenure, not ownership. No one person could claim absolute ownership over a parcel of land, save the King. The feudal laws of escheat grants the King his supremacy — if a lord or tenant dies without an heir, the land returns to the Crown. If an heir wants to take possession of his fief, as in, his inheritance, he must pay a tax to license this possession. Because, you see, land is granted by the King in return for service and allegiance. There is no reason you should receive land without providing a form of service yourself. Your modern understanding of ownership, where an item or object belongs entirely to you yourself, this is not helpful or germane.

Land, lordship, the spatial fragmentation of this country along the fault lines of proprietary interests — I have time to contemplate this all from my corner of the gallery. Yes, it is all very unpleasant, but there you are.

I contemplate the work too — as that is part of my job. If you, a visitor, were to approach me and ask for a guiding hand around the space, I would be contractually obliged. I would say! Welcome and behold! An exhibition by two artists: Sophia Al-Maria and Lydia Ourahmane, titled GREY AND UNPLEASANT LAND… a sly artistic inversion. Yes, this exhibition is about nationhood and a nation’s mythologies!

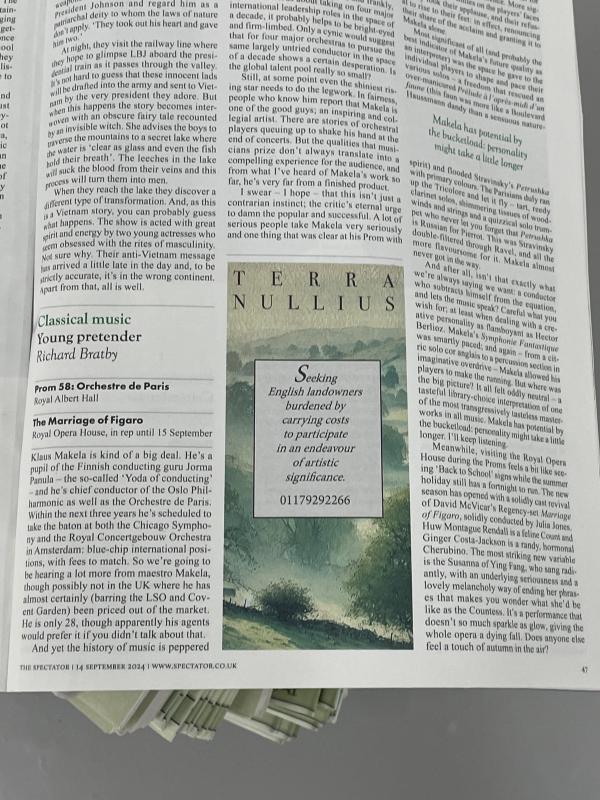

As you walk in, a stack of papers, September issues of the Spectator Magazine, open on a page with an unusual advertisement. TERRA NULLIUS, it reads — that is, Nobody’s Land! A land without a lord! I might fail to mention that lack of allodial land, the parcelling up of every square inch of England, the fact that by law, land must have a lord. But perhaps we esteemed colleagues might understand this all as a motivation for the advertisement’s call to action. Seeking English landowners burdened by carrying costs to participate in an endeavour of artistic significance. And then a phone number with a Bristol area code, where this very gallery is situated — yes, well spotted.

The rest of the work from here appears to us in pairs. Fly Tip: a series of objects scavenged from the streets, illegally dumped and left for dead, the artists have commandeered them and vacuum sealed them in enormous elfbar bags. They take on the shape of monstrous Cronenbergian sculptures — what was once a sofa is now gnarled and whipped into a ghastly aluminium wrapped jagged form. And here, a board, a sink. If you glance to the other side of the gallery, you might spot a set of drawn red velvet curtains hanging on the wall. Rescued from the bin outside 44 Kinnerton Street, Belgravia. The house was in the middle of an estate clearance. Its former owner, Ghislaine Maxwell, had been arrested. Her family were trying to raise funds by selling the house. Curtains and sofa, dumped on the street. Different, the same, disposal is disposal is disposal.

Another pair: Framing Device I and Framing Device II. The carrying frame, support frame and handling frame, as well as the wall text framing it all contextually, for a Pre-Reformation masterpiece — the Wilton Diptych. The painting itself is…. Not present in this gallery. I believe it to be somewhere deep in the National Gallery’s storage facilities. But ah! You should see it! A folding panel from the 13th Century, made for King Richard II. It depicts Richard kneeling before the Virgin, Christ Child and a crowd of angels, flanked by three saints: John the Baptist, Edmund the Martyr and Edward the Confessor. All three saints were the subject of the King’s intense devotion, Edmund and Edward were patron saints of England and former Kings, Richard owned relics of John the Baptist. You will understand, I mean owned in the modern and Medieval sense, for the King owns all. On the back of the panels, a white hart, Richard’s emblem, sits with a golden chain and a golden cuff around its neck. On the front panel, the angels and Richard are wearing matching white hart badges. The angels and Virgin are robed in blue — an expensive colour, it consumes almost the entire right hand panel. The panel is interesting in its absence, this altarpiece that depicts King and God, sainted Kings, angels, heralds. We remember that Kings like Richard believed in their Divine Right to rule, their sovereignty sanctified by God himself — pah! A blessing that couldn’t save his life, for it was Richard’s tyranny that led to his downfall, abdication, imprisonment and death. But isn’t it an interesting sleight of hand, that we speak of the absent panel, when surrounded by the panel’s implements, tools, items and marginalia?

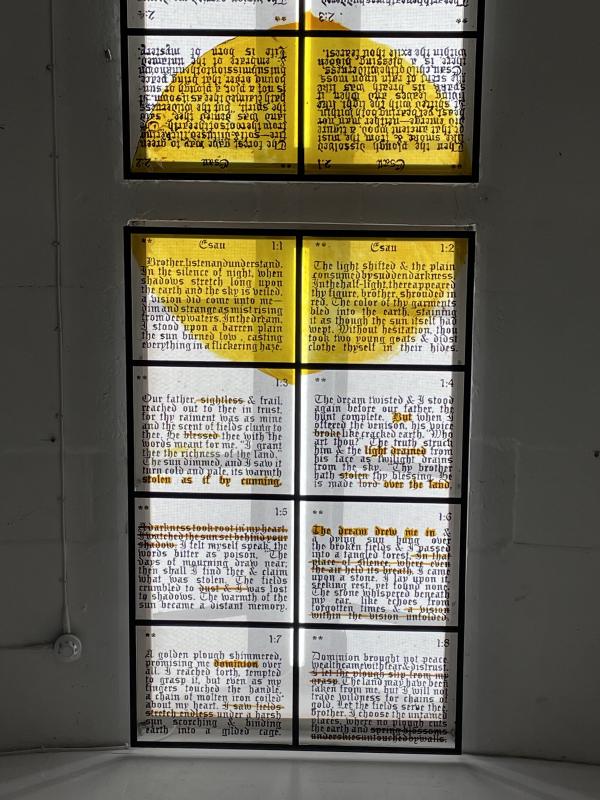

Over on the other end of the gallery, a third pair. A pallet of Scottish sandstone from the same geological seam as the Stone of Scone. Have you heard of this stone? You should know it, you godless English. It was used as a throne to crown Scottish Kings, stolen in the 13th Century by an English King, Edward Longshanks, Hammer of the Scots. Ever since then it has sat under the Coronation Chair in Westminster Abbey — symbolic, is it not? Edward Longshanks invaded Scotland, won, rode to Berwick, forced the Scottish barons to swear fealty to him. The subjugation of Scotland beneath an English King, represented in the capture of this stone, for it to now sit under the chair of all English Kings, forever. You know, the Stone of Scone is rumoured to be the Stone of Jacob. According to the book of Genesis, Jacob tricked his (older) twin brother Esau out of their father Isaac’s blessing of the first-born, and so tricked him out of his inheritance. Jacob fled, making his way to Harran. He stopped for the night in Bethel, taking a stone and laying his head on it to sleep. He had the most unusual dream, seeing a stairway to heaven full of angels, and the voice of God proclaimed that he will give to Jacob and his descendants the land on which he was lying. When he woke, Jacob consecrated the stone and declared Bethel to be the gate of heaven. That is the same stone that rests under the English King’s chair — apparently. But how could it be, when this tonne of Scottish sandstone was quarried from the same place — Perthshire, not Bethel. In this far room we have a stained glass window with a passage about a vision, the dream of Esau. Cheated out of his birthright, he dreams of lying his head on a stone that whispers to him. A golden plough turns into a chain of molten iron, fields bind the earth in a gilded cage. Esau swears his allegiance to the wild places, the untamed land, the blessing of exile. The forest speaks to him in green fire, in bronze serpents, warning him: ‘do not grasp what chains thee, for power is a trap. The earths true gift is not what thou canst hold, but in what thou canst release. Seek not dominion, but knowledge; seek not mastery, but harmony.’ The leaves sing ancient songs to him and Esau understands that he has been spared the burden of his birthright, that it was a kind of curse. A parable for Kings, for those who would place one man above another, is it not? The legal fiction of a sovereign’s divine right, countered by the sacrament of wilderness.

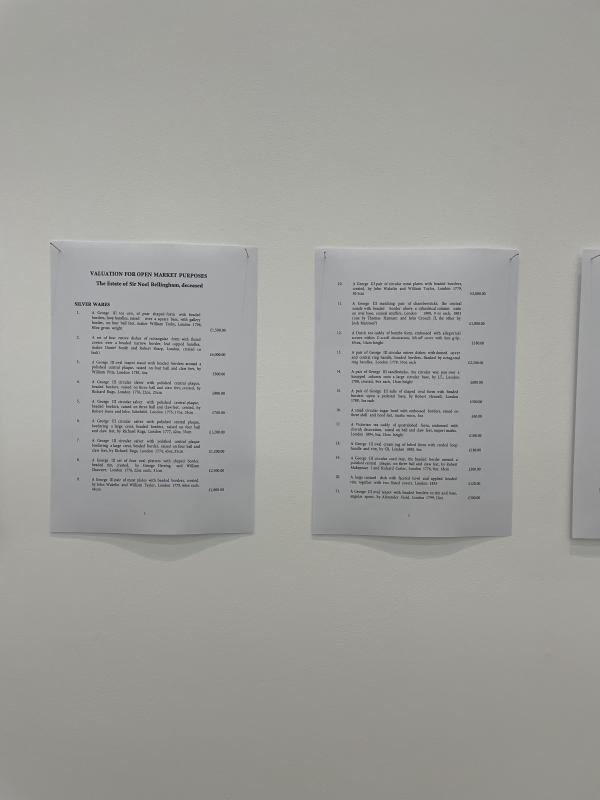

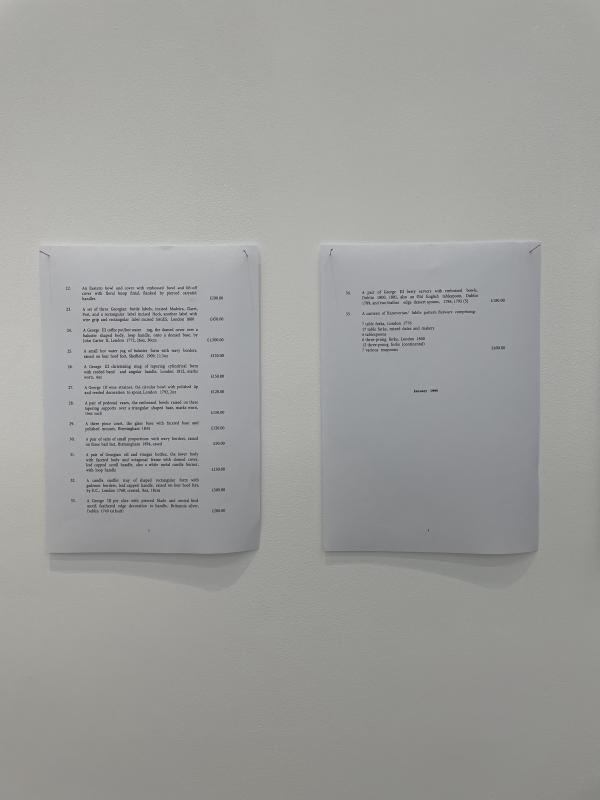

The final pair is perhaps the most interesting. In this central room, in this heart of the gallery we have two inheritances. One belongs to Graham Randles from Liverpool, the other to Sir William Alexander Noel Henry Bellingham, 9th Baronet Bellingham. Graham’s inheritance: 240 porcelain chamber pots, laid out here in a strict grid. Sir William’s inheritance: about £30,500 worth of Georgian silverware. You must assume, as the silver is locked away in these two wooden chests. On the wall there is an itemised list of the contents: salvers with crests and fine etchings, teapots and sugar bowls, candlesticks and cream jugs with decorative allegorical scenes. The chests arrived late, two weeks after this exhibition opened. The artists had to navigate a complex bureaucratic process to retrieve the silver from the heir’s family bank vault. It arrived here in an armoured and insured lorry, it was so heavy it needed to be moved by forklift. Yes, yes. Maybe this is my opportunity to confess to you. If you were an ordinary member of the public, I would say: Only the curators have seen the silver with their own eyes. I couldn’t open the chests for you. They are padlocked shut, the keys resides someplace secret. Technicians have taped the chests shut, creating a kind of seal that would alert security of any breaches. We are only a humble gallery, but our artworks must be kept safe. But I believe we have a… kind of understanding between us. I will clear my conscience.

Of all the diptychs, this one is set to go to auction after the show has closed. The artists have plans to sell the two inheritances together, a job lot of silver service and piss pots. The irony mustn’t be lost. Over in that far corner you will see a newspaper spread — a 2023 issue of the Liverpool Echo where a journalist has interviewed Graham Randles. Graham admits he has been trying to sell the chamberpots on Facebook Marketplace, but has had little luck in shifting them. The silver too. In reviewing this exhibition for the Guardian, one Mr Evan Moffitt remarked that Sir William was inclined to grant the artists access and use of his family silver — it had become something of an emotional burden to him. The Bellingham family has a reputation for losing entire estates in card games. Miraculously, the family silver has survived this profligacy. It too has proved difficult to shift. Until now.

Yes, I, a humble vagabond. I roam where I please, free from the gallery’s complex feudal system. I am tied to no lord, no land. Like Esau, I belong to the wilderness, untamed. Some would see that as a misfortune! I cannot imagine it being anything other than a blessing. Sitting here in my corner of the gallery, watching, waiting, contemplating — I cannot shift from my mind the thought that even if this work went to auction, even if it were to be sold, would it not become a burden to another? Yes, yes, I did not find myself in this job for nothing. I received a vision of my own. It came to me while I lay low in this corner. It came to me, resplendent, magnificent! Under the cloak of darkness I stole into the secret place, happened upon the keys to the chests. The tape lifted and I beheld the treasure within, was near blinded by the horror of it! A fiery forge melted the silver, my own arms hammered and struck it into a new shape. Yes! When the exhibition closed, the curators opened the chest, and they came to find it empty. They found themselves free! Many secrets were revealed to me, secret shapes, secret knowledges. A voice in this mystical vision told me that the artists made this exhibition for a purpose higher than that of standard exhibition and display! Look closely. It is a map. The silver, the stone, the panel. Treasures, burdens, chains — a forge waits for them all! Well… It is but a vision… A joke, you see! I am only the invigilator, one who comes and goes as he pleases. But maybe…

Grey Unpleasant Land was on at Spike Island. Here’s the exhibition page. Here’s the guardian review mentioned in the text.