The Roundabout Artist

ZM

That roundabout had always been a bit of a sore thumb. Not in the way you think. It stuck out because it was so completely lacklustre. As a local, you saw it everyday but… You never really looked at it, or registered it properly. Your eye just glossed right over it, you’d forget you saw it almost immediately. It would slip into an invisible space in your peripheral vision, you’d manoeuvre around it on auto-pilot. When you were walking past, driving, on the bus. You only ever glanced at that little hump of land down by the junction of Victoria Street and Greenford Avenue — you wouldn’t make direct purposeful eye contact. There’s a petrol station, a mini Tesco, a Post Office with the InPost lockers, bike racks. You noticed those, for sure. But not the actual roundabout itself. It was a kind of wasteland, an empty space, a shame, honestly! This is a major capital city, remember? In this squalid urban environment, a roundabout has the potential to be an interesting thing. All it takes is a little something.

It was the first of April, April fools. I was on my way to the petrol station to pick up a newspaper. I’m old school, aren’t I, I still get them in. Can’t beat hard-copy news. But I spotted it out the corner of my eye. I’ve lived round here for 20 years, but it must’ve been the first time I looked at that roundabout directly and specifically. The first time I noticed something different about it. It’s a perfect circle, a green blob with two spindly looking pine trees, a bramble-type looking bush, and it was the middle of Spring, wasn’t it? So the flowerbeds were full of bright yellow daffodils. All normal, but then slap bang in the middle of the roundabout, there was a B&Q wooden garden shed. I remember thinking to myself: that’s unusual, that wasn’t there before. It stuck out.

Now, I’m a nosy person. Can’t help it, it’s just the way I am. When I went into the mini-Tesco to get my paper, I asked the lad on the till about it. He said it was there when he got in for his shift that morning, it wasn’t there last night. The woman scanning her shopping at the self-checkout overheard, said she noticed it too. We mumbled and shrugged because it was a mystery. I came back the next morning and everyone was still none the wiser. I asked Carol at the Post Office, not a clue. The local area was entirely mystified.

The third morning, I got my newspaper from Ranjit at the petrol station. He said he thought he saw someone inside the shed. That set alarm bells ringing for me. I went into the mini-Tesco, told them what was going on. I went into the Post Office and told Carol there too. They all came out to have a look with me. And sure enough, clear as day, we could see it from all the way over the road. Through the plastic window of the shed, a shadow bumbling around inside, doing god knows what. That set us off speculating, didn’t it? Gasps of horror, threats to call the council, the lot. Not that anything came of it then and there. But like I said, I am the nosiest person within the sound of the Bow bells. I thought about that figure in the shed all the way back home, I sat in my armchair, cracked open my paper, barely made it past the breaking news until I was forced to admit — I wasn’t taking in a word. I was too busy thinking about the shed, the person inside. Who were they? What were they up to, why were they here — how were they here? You can’t just set up shop on a roundabout. It’s not on! They could be conducting all sorts of untoward business right under our noses.

Now, I’m a community-minded man. I was in the military. It was a lifetime ago, but it never leaves you. I still know how to handle myself in a situation. I took myself back down the road to the roundabout to investigate and find out what was what. From outside the mini-Tesco, I contemplated the roundabout and the shed. I saw the figure moving inside. The figure looking back at me. I looked to my right, watching for a gap in the traffic. The cars whip round that thing so fast, the corners are basically blind, and don’t even get me started on the motorbikes. There’s no crossing! That never struck me as odd in any way — why would you need a crossing to get to a roundabout? Across a roundabout, sure enough, slap a zebra crossing over it. But to the roundabout? That’d only be useful if you thought of the roundabout as a place to be, and it wasn’t! It was invisible space, proper liminal. I had to dash across. Nearly got knocked over by a Vauxhall Astra. My knees aren’t what they used to be. But once I was across to the other side, on the roundabout — it was like the world went upside down.

Up close and on it, the roundabout was massive, a huge expanse. The trees cast some shade, the bushes muffled the sound of traffic, you could smell the daffodils, I could hear birds. I swear, the sky was bluer. It was an island, set apart from the rest of the area, this semi-suburban concrete sprawl.

I didn’t even get a chance to knock on the door of the shed. He was so glad to see me — wide eyed and beaming, he greeted me with a hug, offered me a cup of tea. He spirited up two camping chairs for us to sit down al fresco. How disarming! I was bamboozled, I had so many questions. How was he powering a kettle on a roundabout? Where was the untoward business I suspected he was conducting? He looked… normal? He was just a normal guy, living in a shed on a roundabout, offering random strangers cups of tea. Up close the world was different, everything was upside down from inside the roundabout.

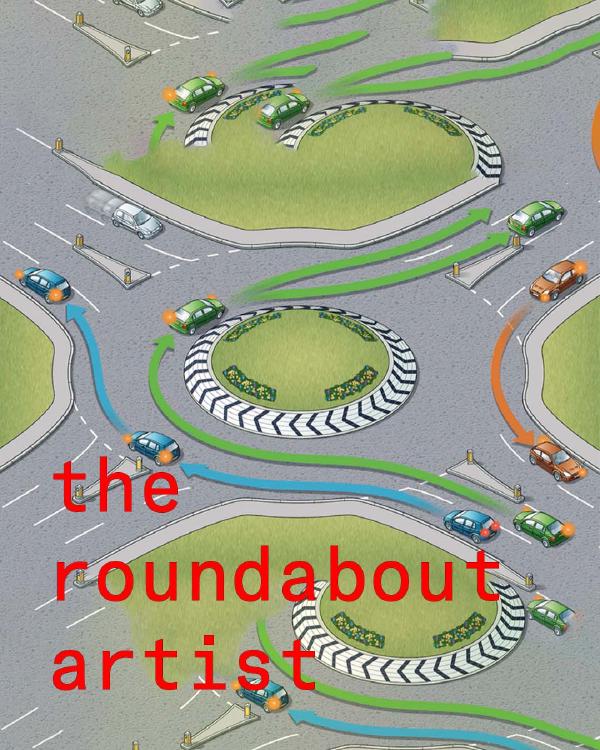

He said his name was John and he was an artist. He specialised in roundabout art. I didn’t know one could specialise in such a thing. He said roundabouts are a very British thing. They are functional, first and foremost they are there to direct traffic safely. And when town planners looked into accident statistics across cities, they found that roundabouts that present a visual obstacle are generally safer. Without something there, drivers are more likely to take a turning like it’s a normal intersection. If you can see right across, you can drive right across. The visual obstacle throws you off, makes you less complacent, you’re more likely to take the time to stop and look, consider and judge the flow of traffic correctly. In Denmark, most of the roundabouts are elevated islands, or they have hedges and trees. But a visual obstacle also offers up an opportunity. There is always the potential for beauty in the everyday! Form as well as function! Enter, The Roundabout Artist.

I guess local councils want to spend their cultural budget in a way that is relatively permanent and very visible. Local councils are local political entities, accountable and beholden to the people they’re elected by. They want everyone to see the art they commission, they also want to tick a box that says they’ve tried to improve public spaces, contributed to public beautification, they want their local area to feel unique and visually identifiable or distinct. John said he didn’t know who the first roundabout artist was, where they put it, when it was. But roundabout art is everywhere, all around us. It is monumental (the literal Arc de Triomphe in Paris is notably a piece of very grand roundabout art). It is small and subtle (the flower beds, the trees, the bushes, landscaping is a creative practice).

Milton Keynes is known as the roundabout city. There are over 130 roundabouts, Milton Keynes City Council even offer a bespoke Roundabout Sponsorship scheme — you can plant flowerbeds in your chosen company colours, have hedges sculpted into shapes of your executive choosing. Cultural activity is the number one factor that determines where people want to live. Not affordability, not transport links — cultural activity. People settle where there’s something going on. As a New Town, Milton Keynes has a huge collection of public sculpture and public art. Liz Leyh’s Concrete Cows have become an unofficial mascot for the city, the home stand at MK Dons football grounds is called the Cowshed, the stadium was once nicknamed the Moo Camp (a riff on Barça’s Nou Camp). But the city’s roundabout art also honours the city’s citizens: Leaping Man is an enormous abstracted silver figure, mid-leap. The artist, Clare Bigger, was commissioned by the council to make the sculpture in honour of Greg Rutherford, an Olympic long jumper born and raised in Milton Keynes. Leaping Man is on the A421 Fen Street Roundabout near junction 13 of the M1, in Woburn Sands, near where Greg Rutherford still lives.

Down by Billingsgate Market, between Poplar and Blackwall, the Trafalgar Way roundabout is home to Traffic Light Tree, a sculpture by Pierre Vivant. It’s a cluster of traffic lights, arranged into the shape of a plane tree, the lights shoot off from one main trunk into different branches and directions. The sculpture used to be on a roundabout in Canary Wharf, on a junction by Heron Quay, Marsh Wall and Westferry Road. It was relocated so the area could be remodelled, but the original location was once home to a huge plane tree that died after being smothered by the city’s air pollution and smog. The lights in the tree flash according to the flurries of activity on the London Stock Exchange, the never ending rhythm of commerce. Traffic Light Tree is a bittersweet monument to the deceased real life tree, the rapid senseless pace and movement of London’s financial district, the way the city itself spreads, devouring and extinguishing the natural world around it.

In the Dutch city of Leiden, there is a roundabout next to the Medical Centre’s parking garage. It is home to a sculptural installation by the artist Merijn Tinga, called Trafficosaurus luminoso. Tinga used black and white striped poles from pedestrian crossings, turning them into 3D stick figures of a nuclear family of horses: a stallion, a mare and a foal. All three horses have lamps for heads. As an artist, Tinga has an interesting back catalogue. From 2003-10 he worked with Joost Haasnoot in a sculptural collective called Kunst Uitschot Team, which translates to ART SCUM TEAM. They would place large wooden sculptures around the city of Leiden, without seeking or receiving permission from the council, local landlords and property owners. Some would say that is illegal, some would say it is a go-getter mentality. The city of Leiden announced its plans for a cultural vision for the city: they wanted to encourage experimentation, support artistic entrepreneurship and initiative, and listen to its citizens. Tinga placed Trafficosaurus luminoso on the roundabout next to the Medical Centre’s parking garage without permission or approval. The artist left a sign next to the work, asking viewers and citizens to participate in a poll and express their opinion about the artwork. After two months, 95% of the responses were in favour of keeping it where it was left, and the Trafficosaurus had 1000 Facebook friends. By the end of the year, Leider’s alderman for culture committed to preserve the Trafficosaurus and uphold the city’s pledge to encourage experimentation, support artistic entrepreneurship and initiative, and listen to its citizens.

John showed me these sculptures on his phone. I had to get my glasses out. I couldn’t really understand what I was looking at, but it was nice enough. John said there’s an Instagram account called @roundabout_sculpture that collects, maps and catalogues roundabout sculptures from across the world. It’s run by Xiao Yang, a Chinese designer based in Spain. The collection is enormous, images of roundabout sculptures from Cambodia to France to Tunisia to Iceland. In its enormity, it highlights the diversity and weirdness of roundabout art as a medium. Lots of the sculptures are deeply strange. A gnome holding a Christmas tree that is also shaped like an anal plug. A basket full of Pineapples. Dinosaurs and dragons popping up out of holes in the ground, emerging from bushes. Enormous year round snowmen. A pot of pencils. A swordfish. Abstract cyclists. Abstract windmills. Abstract yellow hands sticking up towards the sky. Rubik’s cube. Mini Statue of Liberty in France. Mini Eiffel Tower in Indonesia. The abstract, the surreal, the out of place and context. Even the stuff that’s so common it feels normal — it is deeply weird to just have an actual real life plane propped up on a stick, jutting out of the ground at a 45 degree angle.

John said he thinks the strangeness is the entire point. I can’t help but agree. I guess people love rubbernecking whenever they see something unusual or out of the ordinary, a spectacle like a crash or a traffic stop. Why not give them something nice to look at instead? Beauty everywhere, anywhere. But also, once it’s there, what does it do? It’s more than just public safety, isn’t it? That art being on the roundabout defines and recalibrates your relationship to space, to your area, to the world at large around you. If we’re guilty of taking it all for granted, a bit of landscape art throws us off every time, makes us consider it all anew.

I asked John what roundabout art he was going to make now he was here. He shrugged, gestured back at the shed, at me, at my empty cup of tea. He said maybe we were making it right now. Pah! What a lousy cop out. That relational stuff wouldn’t fly round here, we want something site-specific. I told him what I thought would be the best monument to represent the local area. Roadworks. A sculpture about ROADWORKS. They’ve been digging up the main road for so long, I’ve forgotten what life was like before they started, I’ve forgotten when they started. The roadworks on the main road predate recorded history, they’re as old as time itself. And they’re only halfway down the road, they’ve got another half left to do! By the time they’re done they’ll have to start back at the beginning again. The road signs still say completion due July 2025 — hahahaha, NO CHANCE! What a joke. And every time you drive past, of course no one’s working on it. Empty portacabins! I have never seen anyone in so much as a hi-vis vest surveying the scene, not a soul not a clipboard not a hardhat. Make a monument to that. Do a sculpture about that. John laughed, but I was completely serious.

Anyway. That scratched the itch of my curiosity. I thanked John for the cup of tea and made my way back across the road, to the mini Tesco. Then back up the road to my armchair and the paper. I never made it to the sports pages. I was too busy thinking about that moment of confusion, encountering strangeness, disarming people and disrupting the flow of business as usual. That is the whole and entire point of art, or the best point. If the world is made strange, maybe you can see it properly for the first time. Maybe you can make it uninvisible, put aside complacency, stop manoeuvring on auto-pilot and think about where you are and what’s going on around you. And that’s not always just about traffic.